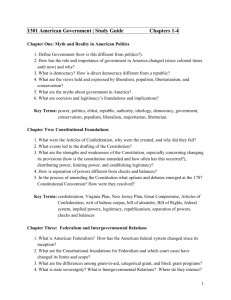

Federalism - International IDEA

advertisement