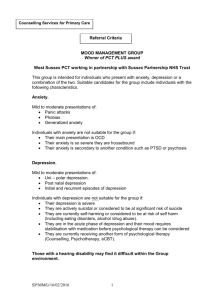

Supporting people with depression and anxiety: a guide for practice

advertisement