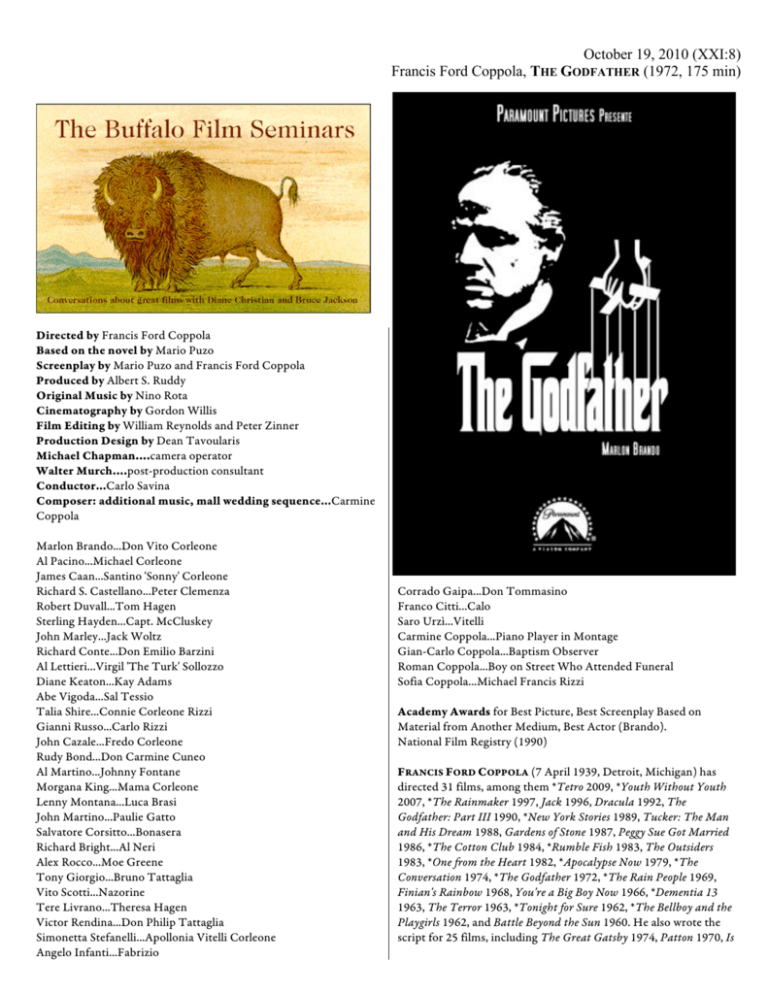

October 19, 2010 (XXI:8) Francis Ford Coppola, THE GODFATHER

advertisement

October 19, 2010 (XXI:8) Francis Ford Coppola, THE GODFATHER (1972, 175 min) Directed by Francis Ford Coppola Based on the novel by Mario Puzo Screenplay by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola Produced by Albert S. Ruddy Original Music by Nino Rota Cinematography by Gordon Willis Film Editing by William Reynolds and Peter Zinner Production Design by Dean Tavoularis Michael Chapman....camera operator Walter Murch....post-production consultant Conductor…Carlo Savina Composer: additional music, mall wedding sequence…Carmine Coppola Marlon Brando...Don Vito Corleone Al Pacino...Michael Corleone James Caan...Santino 'Sonny' Corleone Richard S. Castellano...Peter Clemenza Robert Duvall...Tom Hagen Sterling Hayden...Capt. McCluskey John Marley...Jack Woltz Richard Conte...Don Emilio Barzini Al Lettieri...Virgil 'The Turk' Sollozzo Diane Keaton...Kay Adams Abe Vigoda...Sal Tessio Talia Shire...Connie Corleone Rizzi Gianni Russo...Carlo Rizzi John Cazale...Fredo Corleone Rudy Bond...Don Carmine Cuneo Al Martino...Johnny Fontane Morgana King...Mama Corleone Lenny Montana...Luca Brasi John Martino...Paulie Gatto Salvatore Corsitto...Bonasera Richard Bright...Al Neri Alex Rocco...Moe Greene Tony Giorgio...Bruno Tattaglia Vito Scotti...Nazorine Tere Livrano...Theresa Hagen Victor Rendina...Don Philip Tattaglia Simonetta Stefanelli...Apollonia Vitelli Corleone Angelo Infanti...Fabrizio Corrado Gaipa...Don Tommasino Franco Citti...Calo Saro Urzì...Vitelli Carmine Coppola...Piano Player in Montage Gian-Carlo Coppola...Baptism Observer Roman Coppola...Boy on Street Who Attended Funeral Sofia Coppola...Michael Francis Rizzi Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, Best Actor (Brando). National Film Registry (1990) FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA (7 April 1939, Detroit, Michigan) has directed 31 films, among them *Tetro 2009, *Youth Without Youth 2007, *The Rainmaker 1997, Jack 1996, Dracula 1992, The Godfather: Part III 1990, *New York Stories 1989, Tucker: The Man and His Dream 1988, Gardens of Stone 1987, Peggy Sue Got Married 1986, *The Cotton Club 1984, *Rumble Fish 1983, The Outsiders 1983, *One from the Heart 1982, *Apocalypse Now 1979, *The Conversation 1974, *The Godfather 1972, *The Rain People 1969, Finian's Rainbow 1968, You're a Big Boy Now 1966, *Dementia 13 1963, The Terror 1963, *Tonight for Sure 1962, *The Bellboy and the Playgirls 1962, and Battle Beyond the Sun 1960. He also wrote the script for 25 films, including The Great Gatsby 1974, Patton 1970, Is Coppola—THE GODFATHER —2 Paris Burning? 1966, This Property Is Condemned 1966, The Haunted Palace 1963, as well as the films asterisked earlier in this paragraph.. MARIO PUZO (15 October 1920, New York City, New York – 2 July 1999, Bay Shore, Long Island, New York) wrote 11 novels, some of which were The Dark Arena 1955, The Godfather 1969, Fools Die 1978, The Sicilian 1984, and Omerta 2000. He also wrote or co-wrote a number of screenplays, among them the screenplays for all three Godfather films, and Superman I and II. He was nominated for 14 Oscars and won 5: best director, best picture and best screenplay for Godfather II, best screenplay for The Godfather, best screenplay for Patton. GORDON WILLIS (28 May 1931, Queens, New York) was cinematographer on 37 films, some of which are: The Devil's Own 1997, Malice 1993, Presumed Innocent 1990, Bright Lights, Big City 1988, The Money Pit 1986, The Purple Rose of Cairo 1985, Broadway Danny Rose 1984, Zelig 1983, A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy 1982, Pennies from Heaven 1981, Stardust Memories 1980, Windows 1980, Manhattan 1979, Comes a Horseman 1978, Interiors 1978, Annie Hall 1977, All the President's Men 1976, The Drowning Pool 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Parallax View 1974, The Paper Chase 1973, Up the Sandbox 1972, Bad Company 1972, The Godfather 1972, Klute 1971, Little Murders 1971, Loving 1970, and End of the Road 1970. He received Oscar nominations for Godfather III and Zelig; he won an honorary Oscar in 2009. MICHAEL CHAPMAN (21 November 1935, New York City, New York) was cinematographer for 45 films, among them Bridge to Terabithia 2007, Michael Jackson: Number Ones 2003, Six Days Seven Nights 1998, Primal Fear 1996, The Fugitive 1993, Rising Sun 1993, Kindergarten Cop 1990, Quick Change 1990, Ghostbusters II 1989, Bad 1987, The Lost Boys 1987, The Man with Two Brains 1983, Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid 1982, Personal Best 1982, Raging Bull 1980, The Wanderers 1979, Hardcore 1979, Invasion of the Body Snatchers 1978, The Last Waltz 1978, Fingers 1978, The Next Man 1976, The Front 1976, Taxi Driver 1976,The White Dawn 1974, and The Last Detail 1973. NINO ROTA (3 December 1911, Milan, Lombardy, Italy –10 April 1979, Rome, Italy) composed scores for 168 films, some of which are: Hurricane 1979, Death on the Nile 1978, Fellini's Casanova / Il Casanova di Federico Fellini 1976, “E il Casanova di Fellini?” 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, Amarcord 1973, Love and Anarchy / Film d'amore e d'anarchia, ovvero 'stamattina alle 10 in via dei Fiori nella nota casa di tolleranza... 1973, Sunset, Sunrise / Hi wa shizumi, hi wa noboru 1973, The Godfather 1972, Fellini's Roma 1972, Waterloo 1970/I, “The Clowns” / “I clowns” 1970, A Quiet Place to Kill / Paranoia 1970, Fellini Satyricon 1969, Spirits of the Dead / Histoires extraordinaires 1968, Romeo and Juliet 1968/I, The Taming of the Shrew 1967, “Much Ado About Nothing” 1967, Shoot Loud, Louder... I Don't Understand / Spara forte, più forte, non capisco 1966, Juliet of the Spirits / Giulietta degli spiriti 1965, The Leopard / Il gattopardo 1963, 8½ 1963, Boccaccio '70 1962, The Brigand / Il brigante 1961, Rocco and His Brothers / Rocco e i suoi fratelli 1960, Purple Noon / Plein soleil 1960, La Dolce Vita 1960, The Law Is the Law / La legge è legge 1958, El Alamein / Tanks of El Alamein 1958, Città di notte 1958, Le notti bianche / Le notti di Cabiria 1957, Nights of Cabiria 1957, War and Peace 1956, The Swindle / Il bidone 1955, A Hero of Our Times / Un eroe dei nostri tempi 1955, Modern Virgin / Vergine moderna 1954, Mambo 1954, La strada 1954, Appassionatamente 1954, The Ship of Condemned Women / La nave delle donne maledette 1954, Star of India 1954, I vitelloni 1953, The Assassin / Venetian Bird 1952, The White Sheik / Lo sceicco bianco 1952, The Queen of Sheba / La regina di Saba 1952, The Small Miracle 1951, Valley of the Eagles 1951, His Last Twelve Hours / È più facile che un cammello... 1950, I pirati di Capri 1949, The Glass Mountain 1949, Fuga in Francia 1948, How I Lost the War / Come persi la guerra 1947, The Mountain Woman / La donna della montagna 1944, Giorno di nozze 1942, and Treno popolare 1933. He was nominated for best original dramatic score for The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II; he won the second time out. WILLIAM REYNOLDS (14 June1910, Elmira, New York – 16 July1997, South Pasadena, California) edited 69 films, some of which were Carpool 1996, Ishtar 1987, Pirates 1986, The Little Drummer Girl 1984, The Lonely Guy 1984, Yellowbeard 1983, Author! Author! 1982, Heaven's Gate 1980, Nijinsky 1980, The Turning Point 1977, “The Entertainer” 1976, The Great Waldo Pepper 1975, The Sting 1973, The Godfather 1972, The Great White Hope 1970, Hello, Dolly! 1969, Star! 1968, The Sand Pebbles 1966, Our Man Flint 1966, The Sound of Music 1965, Ensign Pulver 1964, Taras Bulba 1962, Tender Is the Night 1962, Fanny 1961, Wild River 1960, Beloved Infidel 1959, Compulsion 1959, Bus Stop 1956, Carousel 1956, Love Is a ManySplendored Thing 1955, Daddy Long Legs 1955, Desirée 1954, Three Coins in the Fountain 1954, The Outcasts of Poker Flat 1952, The Day the Earth Stood Still 1951, Halls of Montezuma 1950, The Big Lift 1950, The Street with No Name 1948, Give My Regards to Broadway 1948, Algiers 1938, and 52nd Street 1937. He was nominated for 7 Oscars and won 2: The Sting and The Sound of Music. PETER ZINNER (24 July 1919, Vienna, Austria –13 November 2007, Santa Monica) edited 39 theatrical and made-for-tv films, some of which are: Running with Arnold 2006, “10,000 Black Men Named George” 2002, “Conspiracy” 2001, A Gun, a Car, a Blonde 1997, “The Enemy Within” 1994, “Citizen Cohn” 1992, Gladiator 1992, Gengis Khan 1992, “Somebody Has to Shoot the Picture” 1990, Eternity 1989, Saving Grace 1986, War and Love 1985, Running Brave 1983, "The Winds of War" 1983, An Officer and a Gentleman 1982, The Deer Hunter 1978, A Star Is Born 1976, Mahogany 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, Crazy Joe 1974, The Godfather 1972, Darling Lili 1970, The Red Tent 1969, Changes 1969, In Cold Blood 1967, The Professionals 1966, and Wild Harvest 1962. He was nominated for three best editing Oscars and won one: The Deer Hunter. DEAN TAVOULARIS (18 May 1932, Lowell, Massachusetts) had been production designer for 30 films, including all of Coppola’s films Coppola—THE GODFATHER —3 since The Godfather. Some of his other films are Angel Eyes / Ojos de ángel 2001, The Ninth Gate 1999, The Parent Trap 1998, Bulworth 1998, Jack 1996, Rising Sun 1993, Final Analysis 1992, The Godfather: Part III 1990, New York Stories 1989, Tucker: The Man and His Dream 1988, Gardens of Stone 1987, Peggy Sue Got Married 1986, Rumble Fish 1983, The Outsiders 1983, Hammett 1982, The Escape Artist 1982, One from the Heart 1982, Apocalypse Now 1979, The Brink's Job 1978, Farewell, My Lovely 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Conversation 1974, The Godfather 1972, Little Big Man 1970, Zabriskie Point 1970, and Candy 1968. He was nominated for five Oscars and won one: The Godfather: Part II. WALTER MURCH (12 July 1943, New York City, New York) invented the idea of films having a sound designer. He has done sound for 24 films, among them Tetro 2009, Youth Without Youth 2007, Cold Mountain 2003, K-19: The Widowmaker 2002, The Talented Mr. Ripley 1999, Touch of Evil 1958 (sound re-recordist, 1998 restoration), The English Patient 1996, Crumb 1994, Romeo Is Bleeding 1993, The Godfather: Part III 1990, Ghost 1990, Apocalypse Now 1979, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Conversation 1974, American Graffiti 1973, THX 1138 1971, Gimme Shelter 1970, and The Rain People 1969. He has also edited 22 films, some of which are The Wolfman 2010, Tetro 2009, Youth Without Youth 2007, Jarhead 2005, Cold Mountain 2003, K-19: The Widowmaker 2002, The Talented Mr. Ripley 1999, Touch of Evil 1958 (1998 reedit), The English Patient 1996, Romeo Is Bleeding 1993, House of Cards 1993, The Godfather: Part III 1990, The Unbearable Lightness of Being 1988, Apocalypse Now 1979, and Julia 1977. He has been nominated for nine Oscars and won three: Apocalypse Now (sound), The English Patient (sound and film editing). He is the author of two excellent books on film editing, In the Blink of An Eye 2nd ed., 2001, and The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (with Michael Ondaatje) 2004. MARLON BRANDO (3 April 1924, Omaha, Nebraska—1 July 2004, Los Angeles, California) appeared in 42 films, some of which were The Score 2001, The Island of Dr. Moreau 1996, Don Juan DeMarco 1994, Christopher Columbus: The Discovery 1992, The Freshman 1990, A Dry White Season 1989, The Formula 1980, Apocalypse Now 1979, "Roots: The Next Generations" 1979, Superman 1978, The Missouri Breaks 1976, Ultimo tango a Parigi / Last Tango in Paris 1972, The Godfather 1972, The Nightcomers 1971, Burn! 1969, The Night of the Following Day 1968, Candy 1968, Reflections in a Golden Eye 1967, A Countess from Hong Kong 1967, The Appaloosa 1966, The Chase 1966, The Ugly American 1963, Mutiny on the Bounty 1962, One-Eyed Jacks 1961, The Fugitive Kind 1960, The Young Lions 1958, Sayonara 1957, The Teahouse of the August Moon 1956, Guys and Dolls 1955/I, Desirée 1954, On the Waterfront 1954, The Wild One 1953, Julius Caesar 1953, Viva Zapata! 1952, A Streetcar Named Desire 1951, and The Men 1950. AL PACINO (25 April 1940, New York City, New York) has appeared in 46 theatrical and made-for-tv films, among them The Son of No One 2011, “You Don't Know Jack” 2010, Ocean's Thirteen 2007, The Merchant of Venice 2004, "Angels in America" 2003, Insomnia 2002/I, Any Given Sunday 1999, The Devil's Advocate 1997, Donnie Brasco 1997, City Hall 1996, Heat 1995, Carlito's Way 1993, Scent of a Woman 1992, Glengarry Glen Ross 1992, The Godfather: Part III 1990, Dick Tracy 1990, Scarface 1983, Cruising 1980, ...And Justice for All. 1979, Bobby Deerfield 1977, Dog Day Afternoon 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, Serpico 1973, Scarecrow 1973, The Godfather 1972, The Panic in Needle Park 1971, and Me, Natalie 1969. JAMES CAAN (26 March 1940, The Bronx, New York) has been in 102 films and tv series, among them Minkow 2010, Henry's Crime 2010, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2009, New York, I Love You 2009, Get Smart 2008, “Wisegal” 2008, "Las Vegas" 2003-7, This Thing of Ours 2003, Dogville 2003, The Way of the Gun 2000, Mickey Blue Eyes 1999, Bulletproof 1996, Eraser 1996, Bottle Rocket 1996, Misery 1990, Dick Tracy 1990, Alien Nation 1988, Gardens of Stone 1987, Kiss Me Goodbye 1982, Thief 1981, Hide in Plain Sight 1980, Chapter Two 1979, 1941 1979, Comes a Horseman 1978, A Bridge Too Far 1977, Harry and Walter Go to New York 1976, The Killer Elite 1975, Rollerball 1975, Funny Lady 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, Freebie and the Bean 1974, The Gambler 1974, Cinderella Liberty 1973, Slither 1973, The Godfather 1972, “Brian's Song” 1971, Rabbit, Run 1970, The Rain People 1969, "Get Smart" 1969, Submarine X-1 1968, "Wagon Train" 1965, "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour" 1964, Lady in a Cage 1964, Irma la Douce 1963, and "Naked City" 1961. RICHARD S. CASTELLANO (4 September 1933, The Bronx, New York—10 December 1988, North Bergen, New Jersey) appeared in 18 films and tv series, some of which were Dear Mr. Wonderful 1982, "The Gangster Chronicles" 1981, Gangster Wars 1981, Night of the Juggler 1980, "Joe and Sons" 1975-1976, “Honor Thy Father” 1973, Coppola—THE GODFATHER —4 “Incident on a Dark Street” 1973, "The Super" 1972, The Godfather 1972, "N.Y.P.D." 1968-1969, and "Naked City" 1962-1963. ROBERT DUVALL (5 January 1931, San Diego, California) has been in 134 films and TV series or programs, the most recent of which is Crazy Heart 2009. Some of the others are Get Low 2009, The Road 2009, Thank You for Smoking 2005, Assassination Tango 2002, A Civil Action 1998, The Apostle 1997, “The Man Who Captured Eichmann” 1996, Sling Blade 1996, The Scarlet Letter 1995, Geronimo: An American Legend 1993, Falling Down 1993, “Stalin” 1992, Convicts 1991, The Handmaid's Tale 1990, "Lonesome Dove" 1989, Colors 1988, Let's Get Harry 1986, Belizaire the Cajun 1986, The Natural 1984, Tender Mercies 1983, The Pursuit of D.B. Cooper 1981, True Confessions 1981, The Great Santini 1979, Apocalypse Now 1979, Invasion of the Body Snatchers 1978, The Betsy 1978, The Eagle Has Landed 1976, Network 1976, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution 1976, The Killer Elite 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Conversation 1974, The Outfit 1973, Badge 373 1973, Lady Ice 1973, Joe Kidd 1972, The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid 1972, The Godfather 1972, THX 1138 1971, MASH 1970, "The F.B.I." 1965-1969, The Rain People 1969, True Grit 1969, The Detective 1968, "The Wild Wild West" 1967, "The Defenders" 1961-1965, "The Fugitive" 1963-1965, "The Outer Limits" 1964, Captain Newman, M.D. 1963, To Kill a Mockingbird 1962, "Naked City" 1962, "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" 1962, "Armstrong Circle Theatre" 1959-1960, and "Playhouse 90" 1960. STERLING HAYDEN (26 March 1916, Upper Montclair, New Jersey—23 May 1986, Sausalito, California) appeared in 70 films and TV series, among them, "The Blue and the Gray" 1982, Venom 1981, Gas 1981, Nine to Five 1980, Winter Kills 1979, King of the Gypsies 1978, 1900 1976, The Long Goodbye 1973, The Godfather 1972, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb 1964, "The DuPont Show of the Month" 1960, "Goodyear Theatre" 1958, "Playhouse 90" 1957-1958, Five Steps to Danger 1957, The Killing 1956, Top Gun 1955, The Last Command 1955, Naked Alibi 1954, Johnny Guitar 1954, Prince Valiant 1954, Flat Top 1952, Flaming Feather 1952, The Asphalt Jungle 1950, Blaze of Noon 1947, and Virginia 1947. JOHN MARLEY (17 October 1907, New York City, New York—22 May 1984, Los Angeles, California) appeared 155 films and TV series, among them On the Edge 1986, “The Glitter Dome” 1984, The Amateur 1981, "The Incredible Hulk" 1979, "Hawaii Five-O" 19691978, The Greatest 1977, "Baretta" 1975, "Cannon" 1972-1973, The Godfather 1972, "The Bill Cosby Show" 1971, Love Story 1970, Faces 1968/I, "Bonanza" 1968, "Gunsmoke" 1965, Cat Ballou 1965, "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour" 1963-1964, America, America 1963, "Twilight Zone" 1962-1963, "The Untouchables" 1960-1961, I Want to Live! 1958, My Six Convicts 1952, The Mob 1951, and Native Land 1942. RICHARD CONTE (24 March 1910, Jersey City, New Jersey—15 April 1975, Los Angeles, California) acted in 91 films and shows, among them The Return of the Exorcist / Un urlo nelle tenebre 1975, Violent City / Roma violenta 1975, Shoot First, Die Later / Il poliziotto è marcio 1974, No Way Out / Tony Arzenta 1973, The Godfather 1972, Lady in Cement 1968, Tony Rome 1967, Hotel 1967, Synanon 1965, The Greatest Story Ever Told 1965, "77 Sunset Strip" 1963, "The Untouchables" 1961-1962, "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" 1961, Ocean's Eleven 1960, They Came to Cordura 1959, The Brothers Rico 1957, I'll Cry Tomorrow 1955, New York Confidential 1955, Whirlpool 1949, Thieves' Highway 1949, House of Strangers 1949, Call Northside 777 1948, 13 Rue Madeleine 1947, A Walk in the Sun 1945, A Bell for Adano 1945, The Purple Heart 1944, Guadalcanal Diary 1943, and Heaven with a Barbed Wire Fence 1939. DIANE KEATON (5 January 1946, Los Angeles, California) appeared in 56 films and shows, some of which are Morning Glory 2010, Smother 2008/II, The Family Stone 2005, Something's Gotta Give 2003, Town & Country 2001, Marvin's Room 1996, The First Wives Club 1996, Manhattan Murder Mystery 1993, Father of the Bride 1991, The Godfather: Part III 1990, The Lemon Sisters 1989, Radio Days 1987, Crimes of the Heart 1986, Mrs. Soffel 1984, The Little Drummer Girl 1984, Shoot the Moon 1982, Reds 1981, The Wizard of Malta 1981, Manhattan 1979, Interiors 1978, Looking for Mr. Goodbar 1977, Annie Hall 1977, Harry and Walter Go to New York 1976, I Will, I Will... for Now 1976, Love and Death 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, Sleeper 1973, Play It Again, Sam 1972, The Godfather 1972, "Mannix" 1971, "The F.B.I." 1971, "Love, American Style" 1970, and Lovers and Other Strangers 1970. ABE VIGODA (24 February 1921, New York City, New York) appeared in 93 films and shows, some of which are Frankie the Squirrel 2007, Tea Cakes or Cannoli 2000, Farticus 1997, "Law & Order" 1996, "Murder, She Wrote" 1991, Joe Versus the Volcano 1990, Look Who's Talking 1989, Cannonball Run II 1984, "Fantasy Island" 1979, "The Love Boat" 1979, "The Rockford Files" 1974-1978, The Cheap Detective 1978, "Fish" 1977-1978, The Godfather: Part II 1974, "Hawaii Five-O" 1974, The Don Is Dead 1973, The Godfather 1972, and "Suspense" 1949. TALIA SHIRE (25 April 1946, Lake Success, Long Island, New York) is Francis Ford Coppola’s sister. She has appeared in 63 films and shows, some of which are Pizza with Bullets 2010, Minkow 2010, The Return of Joe Rich 2010, The Deported 2009, Dim Sum Funeral 2008, Homo Erectus 2007, I Heart Huckabees 2004, The Landlady 1998, Bed & Breakfast 1991, The Godfather: Part III 1990, Rocky V 1990, New York Stories 1989, "Faerie Tale Theatre" 1987, Rocky IV 1985, Rocky III 1982, Prophecy 1979, Rocky II 1979, Rocky 1976, "Rich Man, Poor Man" 1976, "Doctors' Hospital" 1976, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Godfather 1972, Maxie 1970, and The Wild Racers 1968. Coppola—THE GODFATHER —5 JOHN CAZALE (12 August 1935, Boston, Massachusetts—12 March 1978, New York City) appeared in only six films and one TV series: The Deer Hunter 1978, Dog Day Afternoon 1975, The Godfather: Part II 1974, The Conversation 1974, The Godfather 1972, "N.Y.P.D." 1968, and The American Way 1962. ALEX ROCCO (29 February 1936, Boston, Massachusetts) acted in 149 films and shows, some of which are And They're Off 2011, Now Here 2010, "One Life to Live" 2004, "Walker, Texas Ranger" 2000, "The Simpsons" 1990-1997, Get Shorty 1995, Wired 1989, "Murder, She Wrote" 1985-1986, "The Love Boat" 1983-1984, The Stunt Man 1980, "Starsky and Hutch" 1977, "The Rockford Files" 1977, "Police Story" 1975-1977, The Friends of Eddie Coyle 1973, Slither 1973, The Godfather 1972, Blood Mania 1970, The Boston Strangler 1968, The St. Valentine's Day Massacre 1967, and Motor Psycho 1965 SOFIA COPPOLA (14 May 1971, New York City, New York), who plays the infant Michael being baptized in the church scene, has acted in 16 films, many of them directed by her father, Francis. Some of those films are: CQ 2001, Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace 1999, The Godfather: Part III 1990, Peggy Sue Got Married 1986, Frankenweenie 1984, The Cotton Club 1984, Rumble Fish 1983, The Outsiders 1983, The Godfather: Part II 1974, and The Godfather 1972. She is better known as a director. She has directed seven films, the most recent of which is Somewhere 2010. The others are Marie Antoinette 2006, VOID: Video Overview in Deceleration 2005, Lost in Translation 2003, The Virgin Suicides 1999, Lick the Star 1998, and Bed, Bath and Beyond 1996. Like her father, she is also a screenwriter. She has done seven films thus far: Somewhere 2010, Marie Antoinette 2006, Lost in Translation 2003, "Platinum" 2003, The Virgin Suicides 1999, Lick the Star 1998, and New York Stories 1989. She was nominated for three Oscars, all for Lost in Translation: screenplay, director and picture. She won the first. Francis Ford Coppola, from World Film Directors V. II. Ed. John Wakeman. H.H. Wilson Co. NY 1988 American director, scenarist and producer, born in Detroit, Michigan, second of the three children of Italian-American parents. His father, Carmine, is a flutist who in the course of his career has played in several orchestras including Toscanini’s NBC Symphone Orchestra, which Coppola often conducted on tour. He has also worked as a musical arranger and for years struggled unsuccessfully to establish himself as a composer. Francis Coppola grew up in Queens, New York. He remembers his childhood as “very warm, very tempestuous, full of controversy and a lot of passion and shouting. My father, who is an enormously talented man, was the focus of all our lives. . . Our lives centered on what we all felt was the tragedy of his career.” (That tragedy has now been resolved by Francis Coppola himself, who used his father’s music in The Godfather Part II, Apocalypse Now, and the restored Napoleon.) Talent in the family was not confined to the father. Coppola’s mother, the former Italia Penino, at one time acted in films. His older brother August is a writer and a professor of literature. His younger sister Talia Shire, who appears in both Godfather films, has become well known for her performances in Rocky and Old Boyfriends, and his nephew, Nicholas Cage, has starred in several recent films, Coppola’s Rumblefish and Peggy Sue Got Married among them. As a small boy Francis Ford Coppola (he dropped his middle name in 1977) seemed the least promising member of this ambitious family, “funny-looking, not good at school, nearsighted.” A polio attack when he was nine kept him in bed for a year—a miserable period in which he played with puppets, devoured television, and “got immersed in a fantasy world.” Coppola attributes to this testing childhood the fact that he is a worrier who nevertheless courts trouble: “My wife tells me I put myself in these tight spots to justify my anxiety.” Coppola made his first movies at the age of ten with his father’s 8mm camera and tape recorder. In high school his interests broadened to include writing, music, cinema, and the theatre. About the time he graduated from Great Neck High School, Long Island, he discovered the films of Eisenstein. Coppola became so ardent a disciple that, though he was “really dying to make a film,” he chose to seek a rounded theatrical education first “because Eisenstein had started like that.” In 1956 he entered Hofstra College (now University) on a drama scholarship and almost immediately made a stir with an anti-administration story in a student magazine. In this and later student pieces his biographer Robert K. Johnson finds early evidence of Coppola’s predilection for “fast-paced, episodic structure,”his interest in technology, his fascination with determined women, and his natural rebelliousness.” At Hofstra, eager to master every aspect of the theatre, Coppola acted in student productions, worked on lighting and stage crews, wrote dialogue and lyrics. He won the Dan H. Lawrence Award for his direction for O’Neill’s The Rope and sealed his reputation by conceiving, producing, and directing Inertia, the first play ever written and staged entirely by Hofstra students. He also founded a cinema workshop at the college, sold his car to buy a 16mm camera, and worked on a movie that he never finished. In 1960 Coppola went on to the UCLA film school. He was a graduate student but younger than most of the others, and he was lonely and disappointed. No one at UCLA seemed to share his interest in the dramatic bases of the cinema except the veteran director Dorothy Arzner, one of his teachers. Desperate to “fool around with a camera and cut a film,” he shocked the other students by hiring himself out as a director of porno films, then appalled them by going to work for Roger Corman. Corman was in those days despised as a cheapskate manufacturer of exploitation movies, though even then it was clear he was prepared to take chances on talented young filmmakers. Coppola’s first job for him was to dub and reedit a rather Coppola—THE GODFATHER —6 sentimental Russian science-fiction film, turning it into a sex-andviolence monster movie called Battle Beyond the Sun (1962). Corman paid him $200 for six months’ work but gave him his first screen credit (as “Thomas Colchart”). Often working all night (and making sure that Corman noticed), Coppola created a place for himself as dialogue director, sound man, and “all-purpose guy.” He got his first directorial assignment by exploiting Corman’s notorious stinginess, Filming in Ireland in 1962, he pointed out that it was a pity to bring a crew so far for a single movie, and sold Corman on an idea of his own on the strength of a single ghoulish scene. Shooting began soon afterwards on a script that Coppola had written in three days, and he invited some of his American friends over to Ireland to join in. One of them was his set director Eleanor Neil, whom he married the same year. Dementia 13 was made for forty thousand dollars. It is a grisly confection of no great distinction about inheritances and ax murders, but it seem to Coppola now “the only film I ever enjoyed working on.” Before 1962 was over Coppola, still enrolled at UCLA, won the Samuel Goldwyn award for a scenario and on that account was hired as a scriptwriter by Seven Arts (later Warner Brothers-Seven Arts). He made adaptations —later much rewritten by others—of Carson McCullers’ Reflections in a Golden Eye and Tennessee Williams’ This Property is Condemned, and in collaboration with Gore Vidal wrote Is Paris Burning? Frustrated by his inability to get a film made in his own way, he personally bought the rights to David Benedictus’ novel You’re a Big Boy Now, fusing it in his adaptation with a story idea of his own. He made the picture “on hope and credit,” with some backing from Seven Arts plus the fifty thousand dollars he had earned as coauthor of Patton (a script that brought him an Oscar when it was eventually released in 1970.) Coppola mustered a notable cast for You’re a Big Boy Now. Peter Krastner plays Bernard, a naive young man working in the New York Public Library. He is dominated by his parents (Geraldine Page and Rip Torn), jealously guarded by his landlady (Julie Harris), and pursued into impotence by a deviant actress (Elizabeth Hartman), who preserves as a trophy the artificial leg of her first seducer. In the end. after fearful travails, Bernard becomes a man in the arms of a sexy librarian (Karen Black). It was Coppola’s first “personal” film, and he only had twenty-nine shooting days. It was Coppola’s first “personal” film, and he had only twenty-nine shooting days. He rehearsed his actors as if for a play and actually staged a public performance, videotaping it to check which moves and lines worked best. The uncertainty revealed by this “market research” is characteristic of Coppola and is revealed in the movie itself, which rather uneasily combines several different modes of humor. There is grotesque social satire, parody (of certain plays and films), and manic visual humor in the manner of Richard Lester— fast motion, jump cuts, captions, and charming absurdities like a girl glimpsed reading in a fountain. Structurally weak as it is, You’re a Big Boy Now is perhaps the most likable of Coppola’s films—funny, fastpaced, and often perceptive and original in its characterization. It was much discussed and warmly praised by many critics as the debut of a new director of great talent and promise—the first such produced by a university film school—but it was overwhelmed at the box office by a slicker movie on a similar theme, Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Offering You’re a Big Boy Now as his thesis, Coppola left UCLA with a master’s degree in 1967. It was at about this time that he made his much-quoted statement about patterning his life on Hitler’s, later explaining that “the way to come to power is not always to merely challenge the Establishment, but first make a place in it and then challenge, and double-cross, the Establishment.” Guided by this philosophy, Coppola agreed to direct a screen version for Warner Brothers-Seven Arts of the 1940s Broadway musical Finian’s Rainbow, a dated and improbably whimsy about leprechauns and racial integration. He was out of his depth and “faking it” much of the time but—until the picture bombed on release—Warners were delighted and blew the film up from 35mm to 70mm (thus chopping off its principal asset, Fred Astaire’s feet). Finian’s Rainbow introduced Coppola to George Lucas, a young film school graduate who served as production assistant on Coppola’s next film and brought in his friend Walter Murch to handle sound. The Rain People, written and directed by Coppola, was financed by him too until his money ran out (when Warner Brothers-Seven Arts chipped in). It stars Shirley Knight as a Long Island housewife who feels that she is losing her identity in marriage. Finding herself pregnant and fearing total engulfment, she leaves her husband and drives off across America in search of herself. James Caan plays the brain-damaged football player who becomes her surrogate child, and Robert Duvall the cop who seems to offer her sexual freedom. Traveling west with a small crew in a remodeled bus, Coppola wrote the script as he went. “We just drove,” he says, and when they found a likely setting it was written into the picture. The result was sloppy in construction but rich in unstereotypical character studies; an American travelogue and a feminist film ahead of its time (but one, as its director admits, with “a deus ex machina and a very emotional plea to have a family”). In 1969 Coppola established American Zoetrope in a San Francisco warehouse. Financed by Warners, it is a small but splendidly equipped studio for editing, mixing, and sound recording, and Coppola has continued to use it for these purposes. But in the beginning it was conceived as something very much more—a base from which to launch a revolution in the American film industry. According to Lucas, Zoetrope’s vice president, they hoped to make seven or eight films a year, some of them “safe and reasonable” to pay for others that would be “really off-the-wall productions. It was a way to give first-time directors a break and do what studios ordinarily would not do.” Coppola—THE GODFATHER —7 American Zoetrope in its original manifestation collapsed after a year or so. But not before Coppola had begun what has been seen as a “Hollywood Renaissance.” Thousands of young filmmakers wrote to Zoetrope or visited or sent their films. Unfortunately, many exploited the place, stealing or breaking the equipment. The high hopes faded as the money ran out, and Coppola’s own reputation suffered when both Finian’s Rainbow and The Rain People failed on release. Zoetrope’s first film—Lucas’ THX-1138—was also its last. Warners, who were to distribute the Zoetrope products, disliked the picture and asked for their money back. At thirty, Coppola was three hundred thousand dollars in debt and apparently finished as a filmmaker. At that low point, Coppola was invited by Paramount to direct a major film based on Mario Puzo’s bestselling Mafia novel The Godfather. It was not an easy picture. The crew at first had little faith in Coppola, who also had to fight hard to persuade Paramount to accept the stars he wanted and to make the film “in period.” There was bitter opposition from the Italian-American Civil Rights League (whose president, an alleged mobster, was shot at a Columbus Day rally during the filming). And Coppola had his usual difficulty in deciding how to end the film. It is a study of a powerful Mafia family at the end of World War II, opening at the home of the patriarch, Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando), on his daughter’s wedding day. The family’s tame politicians and judges send their apologies for absence, and we encounter Vito’s son Michael (Al Pacino), a college-educated war hero who so far has disdained to take part in the family “business.” The film follows the gradual transfer of power from the Don to Michael, who is blooded in avenging an attack on his father. The old man dies peacefully, and the Corleones, led by Michael, wipe out their rivals in a bloodbath that coincides with the christening of Michael’s godson: “The gold and pomp of the Church,” as one critic wrote, “against the brutish, bloody machinations of the family”—a recurrent device in the film. Michael assures his troubled wife that he had nothing to do with the slaughter, but before the door closes and the screen goes dark, she sees the mafiosi trooping in to swear fealty to the new Don. The Godfather is immensely dramatic and exciting—a “dynastic romance” told with “a marvelously operatic use of pomp and violence,” It opens the door on the mores and rituals of an exotic subculture, and it is one of the great gangster films. Robert K. Johnson suggests that “no other film has so imaginatively presented murder in such a variety of visually vivid ways,” and Jay Cocks thought it “a mass entertainment that is also great movie art.” Serious claims have been made for it as an indictment of American capitalism, and Coppola encouraged this view by saying that the Mafia “is no different from any other big, greedy, profit-making corporation in America.” His opponents replied that if he had intended this sort of criticism, he should not have glamorized the Corleones (as many contended that he had). There was some disagreement also about Brando’s Oscar-winning performance as the Don—a masterpiece in the opinion of the majority, but a matter of “studied but easy effects” in Stanley Kauffmann’s judgment. The Godfather won an Academy Award as the best picture of 1972, and Coppola received an additional Oscar as coauthor (with Puzo) of the best script based on material from another medium. Financially the film was staggeringly successful—at that time the most profitable movie in history, making more than a million dollars a day in profit for months after it was released. It recouped all of Coppola’s losses and made him rich. For a time after it was finished he involved himself in less strenuous projects, including two stage productions in San Francisco—Noel Coward’s Private Lives and Gottfried von Einem’s opera The Visit of the Old Lady. It was at this time that Coppola joined with William Friedkin and Peter Bogdanovich to form the Directors Company, a Paramount-backed consortium that in the end turned out only two movies— Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon and Coppola’s The Conversation. Coppola’s fascination with technology is at the center of The Conversation, which he wrote, directed, and coproduced. It is a study of a professional eavesdropper, Harry Caul, who is splendidly portrayed by Gene Hackman. One day, using a rifleshot microphone, he records a conversation between two young people that he cannot at first decipher, though he knows that it concerns murder. He eventually clarifies the significant phrase but, because he knows more about technology than most people, he misinterprets it. An obsessively private man, he nevertheless intervenes, and he is destroyed. Influenced by Hitchcock, Clouzot, and Antonioni’s Blow-up, the film owed much to Walter Murch, who handles both sound and editing and, according to some accounts, is primarily responsible for the brilliant interlacing of sound and image that gives the picture its unique quality. It won the Golden Palm as best film at Cannes in 1974. The Godfather Part II carries the story both backward and forward in time. It begins in 1901 in Sicily, where a young boy is orphaned by vendetta. He is Vito Andolini (soon to be Corleone) and he emigrates to America; we see him (now played by Robert De Niro) finding his feet in New York, battling the Black Hand, and emerging as a power in the neighborhood. The film ends with his “respectable” son Michael in a position of unassailable power but without a wife, brothers, friends, or any vestige of common humanity. Coppola was anxious to correct the impression that he admired the Corleones and to some extent he succeeds—if Vito as a young man has something of the Robin Hood in him, his son at the end is wholly-corrupted and cold-hearted. Indeed, the darkness that surrounds Michael at the end of the film is a measure of his achievement: he is lord of the underworld, and king of the dead and the damned. A more analytic film than its predecessor, greatly Coppola—THE GODFATHER —8 admired for the loving recreation of old New York in the early scenes, The Godfather Part II won Oscars for best picture, best director, best script (Coppola and Puzo), best supporting actor (De Niro), and best original score (Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola). Coppola’s position in the movie industry now seemed assured. He put more money into the technical resources of American Zoetrope, invested in real estate, and bought a New York film distribution company. He also bought eighty percent of City, a San Francisco news weekly that reportedly lost him one-and-a-half million dollars before it folded. And by late 1975 he was at work on another movie, Apocalypse Now—a version of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness updated to the Vietnam War. John Milius had written the original script under Coppola’s sponsorship years before, when George Lucas was to have directed it. Now Coppola took the project over. It tells the story of Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), an Army officer with CIA connections, who is sent upriver from Saigon to “terminate” a certain Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), a brilliant officer who has gone off the rails and established a private kingdom in Cambodia. Shooting began in the Philippines in March 1976 and continued on and off for sixteen months, hindered by every conceivable kind of problem. Coppola replaced his leading actor, with great difficulty, after filming had begun. Typhoon Olga destroyed the sets. Martin Sheen had a heart attack. Before the film was finished, Coppola had mortgaged everything he owned to cover personally some sixteen million dollars of the thirty million it cost. Nor was the price only financial. Eleanor Coppola, who went to the Philippines to make a documentary about the filming, has written a book about the ordeal and the strains it placed on the marriage. In March 1977 she wrote of Coppola in her diary: “I guess he has had a sort of nervous breakdown. . . .The film he is making is a metaphor for a journey into self. He has made that journey and is still making it.” Editing continued throughout 1978, with Coppola unable to decide how to end the film: “Working on the ending is like trying to crawl up glass by your fingernails.” He even arranged previews of the picture as “a work in progress,” hoping to learn from audience reactions how best to complete it. Apocalypse Now had its world premiere in May 1979 at the Cannes Film Festival, where it was joint winner of the Golden Palm, and was released in the United States a few months later. There was something like universal praise for the way Coppola handles Willard’s journey up the river—notably his encounter with an air cavalry colonel (Robert Duvall) who loves “the smell of napalm in the morning” and whose helicopters attack to “The Ride of the Valkyries.” Richard Roud called this passage “terrifying, beautiful, exciting, funny and disgusting, almost simultaneously.” What happens when Willard reaches Kurtz’s empire of ancient temples and dangling bodies seemed to most reviewers an anticlimax—we meet not the embodiment of evil but “an eccentric actor who has been given lines that are unthinkable but not, unfortunately unspeakable.” About the film as a whole, opinions differed radically. David Robinson called it a “catastrophe...a majestic, failed enterprise,” while Philip French thought it “a towering achievement, one of the major pictures of the past few years.” Vincent Canby (one of the many who praised Vittorio Storaro’s photography) concluded that “individual scenes and images have tumultuous life but the end effect of the film is of something borrowed and not yet understood.” At the box office the film was a major success, and Coppola rose once more from the ashes, his much-discussed plans for a quieter life apparently forgotten. He was soon gearing up a variety of projects for friends and protegés, starting with a script about the flamboyant carmaker Preston Tucker, and making notes for “a more personal, more theatrical film”—a love story set in Japan and America and based on Goethe’s Elective Affinities. Late in 1979 he was negotiating for the Hollywood General production lot in Los Angeles and Zoetrope, reestablishing this time as “a little factory, like a Republic or an RKO, making one movie a month in the old style and at an intelligent price. But I believe we’ll be the first all-electric movie studio in the world. . .It just takes the wisdom and the guts to invest in the future.” The same year Zoetrope brought our The Black Stallion directed by Carroll Ballard, with Coppola executive producing, but despite that film’s broad critical success, the studio was by no means financially equipped for Coppola’s next directorial effort, One From the Heart (1982). When foreign investors suddenly withdrew support in the midst of production, Coppola mortgaged everything he owned— including Zoetrope and his own homes—to complete the ambitious undertaking. ...Though the sets [designed by Dean Tavoularis], as well as the music by Tom Waits, received praise, the film as a whole was a critical and box-office flop.... The artistically adventurous features that Zoetrope produced or co-produced in the early ‘80s (Hammett, The Escape Artist and Koyaanisqatsi among them, with Kurosawa’s Kagemusha perhaps Coppola’s pet project) did little to help the studio’s flagging financial resources, and in 1982 Coppola was forced to sell Zoetrope. He did not, however, declare bankruptcy but instead undertook to repay the debts he had incurred with One From the Heart. Ripe for projects with more popular appeal, Coppola took on the task of Coppola—THE GODFATHER —9 filming The Outsiders, a novel for teenagers by S.E. Hinton. Coppola had been “selected” by a group of high school students as the ideal director for a film version about rich and poor adolescents in Oklahoma, and upon reading the book, Coppola agreed with them. He immediately began filming with Matt Dillon in the lead, and tried to cultivate a genuine rift between the young actors playing underprivileged “greasers” and those playing wealthy “socs” to effect realistic confrontations on the screen. Coppola was so pleased with his progress that he decided in the middle of making The Outsiders to use the same crew and some of the same actors to make a second Hinton adaptation from her novel Rumble Fish. This dreamy blackand-white film depicts the darker side of the gang dynamics seen in The Outsiders, and pursues the theme of competition between brothers that Coppola has returned to repeatedly. Dillon again starred, with Dennis Hopper and Mickey Rourke in supporting roles; the film was dedicated to Coppola’s older brother August. At first dismissed as exploitation pictures, these two films have intrigued later critics, who have discerned here an inventive and unabashed romanticism at play in the confines of genre. Coppola worked closely with Hinton during the filming and achieved an unusual degree of creative control, especially over Rumble Fish, which is one of his own favorites. But as Richard Jameson remarked, a picture designed as “an art film for teenagers” ran the risk of bewildering its intended audience, who lack “a lexicon for its arty codes.” Faced with such discouraging responses and still owing an enormous sum of money, Coppola felt “the key is to keep working....It’s annoying to have to work so much to pay for thing that happened in the past. But I’m tougher for it. I think I’ll come out all right.” Though Zoetrope was honored with a retrospective at the 1983 Santa Fe Film Festival, and Coppola himself received the Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters from France in 1984, he could not have found backing for his independent projects at this time, and so responded positively to Robert Evans’ plea for help with a “sick child”: The Cotton Club. Evans had originally intended to direct the film about the famous Harlem nightclub himself, but when it became mired in financial and legal problems he brought in Coppola to placate the film’s investors. Coppola wrote almost forty versions of the script, working at first with Mario Puzo and then with novelist William Kennedy, finally coming up with a plot that blended classic Hollywood gangster and musical genres.... Coppola directed portions of the film from an elaborately equipped electronics van parked outside each location. ...Because the $47-million film was so technically complex and was repeatedly interrupted by litigation (following one series of lawsuits Evans lost ownership of the film; in a contract dispute, Coppola temporarily withdrew from the project) Coppola never achieved the creative control he sought, probably fulfilling his own dictum that “more money means less freedom.” Pauline Kael wrote that in Cotton Club “Coppola, seemingly tormented by his inability to fulfill his own ideas and talents, took refuge in unsubtle stylistics.” ...The emphasis on huge, state-of-the-art production methods that contributed to the expense and difficulty of making The Cotton Club nonetheless engaged Coppola more and more. In 1985 he made his first work for television, a dramatization of “Rip Van Winkle” for cable television. Coppola crafted many of the fantastic scenes in the fairy tale with computer imaging systems that allow for the exact imposition of many separately filmed images. He found the video medium very much to his liking, and hired Eiko Ishioku, who had done surrealistic sets for Paul Schrader’s Mishima, a 1985 film about Japanese author Yukio Mishima that Coppola helped produce, to design the sets for “Rip Van Winkle.” Though the director’s reliance on technology was faulted in The Outsiders and One From the Heart for distancing him from his work, Coppola insists that “film is already like the horseless carriage. Film is beautiful, but it is dead, it is not any longer relevant. The new medium, video, is so incredibly flexible and immediate and economical and can be as beautiful that it’s bound to take over.” In 1985 Coppola was able to indulge all his high-tech excitement in making Captain Eo, a 12-minute space fantasy starring (and with songs by) Michael Jackson, produced by George Lucas and with camerawork by Vittorio Storaro. The film will be shown only at Disneyland and Disney World, on huge Imax screens that emanate fog and laser beams…. Coppola swings between epic, high-tech behemoths and intimate studies and his uneven success rate are characteristic of many directors of his generation, according to David Sterritt, who maintains that Cimino, Scorsese, Spielberg and Coppola face “the difficulty of joining personal expression with big money and flashy show-biz traditions.” But despite his track record, the film industry has treated Coppola with unusual lenience, perhaps because, as producer Irwin Jablans has said, “he’s the last, or maybe just the latest, of the great old larger-than-life American directors. His failures are more interesting than many other directors’ hits.” “Castro-bearded and restless,” immensely knowledgeable about every aspect of filmmaking, Coppola has been described as “still something of the enthusiastic schoolboy egghead.” ...[His] second son was killed in a boating accident in 1986. “You know what it’s like to be a director?” he said once. “It’s like running in front of a locomotive. If you stop, if you trip, if you make a mistake, you get killed.” Coppola’s own career bears this out, but he has always refused to stay dead, and he has breathed life into those around him. “He subsidized us all,” John Milius says. “George Lucas and me. Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, who wrote American Graffiti, Hal Barwood, Matt Robbins...He is responsible for a whole generation; indirectly he is responsible for Scorsese and De Palma. You cannot overemphasize the importance he had. If this generation is to change American cinema, he is to be given the credit, or the discredit.” Coppola—THE GODFATHER —10 from The Great Movies. Roger Ebert. Broadway Books, NY, 2002. “The Godfather” The Godfather (1972) is told entirely within a closed world. That’s why we sympathize with characters who are essentially evil. The story by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola is a brilliant conjuring act, inviting us to consider the Mafia entirely on its own terms. DonVito Corleone (Marlon Brando) emerges as a sympathetic and even admirable character; during the entire film, this lifelong professional criminal does nothing that, in context, we can really disapprove of. We see not a single actual civilian victim of organized crime. No women trapped into prostitution.No lives wrecked by gambling. No victims of theft, fraud, or protection rackets. The only police officer with a significant speaking role is corrupt. The story views the Mafia from the inside. That is its secret, its charm, its spell; in a way it has shaped the public perception of the the Mafia ever since. The real world is replaced by an authoritarian patriarchy where power and justice flow from the Godfather, and the only villains are traitors. There is one commandment, spoken by Michael (Al Pacino): “Don’t ever take sides against the family.” It is significant that the first shot us inside a dark, shuttered room. It is the wedding day of Vito Corleone’s daughter, and on such a day a Sicilian must grant any reasonable request. A man has come to ask for punishment for his daughter’s rapist. Don Vito asks why he did not come to him immediately. “I went to the police, like a good American,” the man says. The Godfather’s reply will underpin the entire movie: “Why did you go to the police? Why didn’t you come to me first? What have I ever done to make you treat me so disrepectfully? If you’d come to me in friendship, then this scum that ruined your daughter would be suffering this very day. And, if my chance an honest man like you should make enemies...then they would become my enemies. And then they would fear you.” As the day continues, there are two more séances in the Godfather’s darkened study, intercut with scenes from the wedding outside. By the end of the wedding sequence, most of the main characters will have been introduced, and we will know essential things about their personalities. It is a virtuoso stretch of filmmaking: Coppola brings his large cast onstage so artfully that we are drawn at once into the Godfather’s world. The Annotated Godfather: The Complete Screenplay. Jenny M. Jones. Black Dog & Levanthal, NY, 2007. “What are they getting so excited about? It’s only another gangster picture.” Marlon Brando, 1971. Looking back thirty-five years after the release of The Godfather, one can’t help but marvel how the film ever got made, when every conceivable obstacle stood in its way. A writer who didn’t want to write it. Mario Puzo was broke and needed to pen something commercial in order to write the kind of books he really cared about. A studio that didn’t want to produce it. The box-office failure of previous gangster movies made Paramount Pictures reluctant to pick up their option, but with the novel a runaway success, and other studios showing interest, they couldn’t let it slip away. A film no director would touch. Twelve directors turned it down, including, at first, Francis Ford Coppola. But Coppola, too, was broke, and needed a job directing a Hollywood production in order to make the kind of personal films he really cared about. A cast of unknowns. Except for one renowned actor, Marlon Brando, who was considered box office poison by studio executives. A community against it. Before filing even began, ItalianAmerican groups protested what they perceived was to be the movie’s characterization of their culture, and amassed a war chest to stop the production. And yet, The Godfather succeeded beyond anyones wildest imagination, to become one of the greatest cinematic masterpieces in history—a film that continues to captivate decades after its release. The Godfather is a unique film in that it bridges many audiences, appealing to both erudite film buffs and TV couch potatoes alike. As film critic Kenneth Turan says, it is irresistible: “Like one of those potato chips, you can’t have only one of it. It is a film that once started or stumbled upon on TV, demands to be seen all the way to the end. It is that well-constructed, that hypnotic, simply that good.” Even Al Pacino admits that when he’s flipping the channels and comes across The Godfather, he can’t help but keep watching. But why is the film still so compelling today? Certainly the thrill of looking inside the particular subculture that The Godfather explores. in conjunction with the movie’s intense action and drama, is endlessly entertaining. There are two other central reasons to love the film. The first is in the details. With each new viewing, a different, distinct detail reveals itself: the jarring crunch of gravel under Michael’s feet after Carlo is murdered; the blustery performance of Sterling Hayden; the exquisite marriage of Nino Rota’s haunting score with the dazzling Sicilian landscape. The details are no accident. In addition to Coppola’s dogged efforts to infuse the film with the flavor and intricacies of his own ItalianAmerican experiences, he assembled an incredible collection of talent to create the film. From the cinematographer to the production designer, from the makeup artist to the special-effects wizard, from the costume designer to the casting director, from Brando to Pacino—only today can the wonder of such a gifted group, working together on one movie set, be fully appreciated…. Coppola—THE GODFATHER —11 The screenplay of the 1972 film featured herein incorporates much of Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo’s own wording from their final, pre-production draft or shooting script (officially titled “Third Draft,” completed on March 29, 1971. This look back at the monumental film also traces the development of the screenplay and explores the evolution of several subsequent versions and re-edits of the film that appeared after 1972. Among those different versions are The Godfather Saga, a four-part miniseries broadcast on NBC in 1977, which combined The Godfather and its sequel, The Godfather: Part II, in mostly chronological order, with some restored scenes that did not appear in the original theatrical release; The Godfather 1902-1959: The Complete Epic (a.k.a. Mario Puzo’s The Godfather: The Complete Novel for Television), a video boxed set released in 1981 in the same format as Saga but with fewer restored scene; and The Godfather Trilogy: 1901-1980, a re-editing of all three Godfathers in mostly chronological order, with even ore additional footage, released in 1992. because Jews made them, not Italians. So they sought an ItalianAmerican director, a commodity in short supply. Bart thought of twenty-nine-year-old he had met when he had written a piece for The New York Times on a young wannabe director who paid his way through college by making “nudies,” otherwise known as skin flicks….Peter Bart first approached Coppola to direct The Godfather in the spring of 1970. Coppola tried to read the book but found it sleazy. His father advised him that commercial work could fund the artistic pictures he wanted to make. His business partner, George Lucas, begged him to find something in the book he liked. He went to the library to research the Mafia, and became fascinated by the families that had divided NewYork and run it like a business. Coppola reread the novel and came to see a central theme of a family—a father and his three sons—that was in its own way a Greek or Shakespearean tragedy. He viewed the growth of the 1940s Corleone family as a metaphor for capitalism in America. He took the job. ...When Paramount gave The Godfather the green light, finding a director turned out to be a difficult task. Twelve directors turned down the job many, including Peter Yates (Bullitt) and Richard Brooks (In Cold Blood), because they didn’t want to romanticize the Mafia. Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde, Little Big Man) was too busy. Costa-Gavras (Z) thought it too American. Robert Evans, Paramount’s head of production, sat down with Peter Bart, his creative second in command, to determine why previous organized crime films hadn’t worked, and decided it was Gene Phillips, in The St. James Film Directors Encyclopedia. Ed. Andrew Sarris. Visible Ink, Detroit 1998: In 1990 he made his third Godfather film. This trilogy of movies, taken together, represents one of the supreme achievements of the cinematic art. Michael Chapman said: “Stills and movies, philosophically, are completely different. One is about stopping time, the other about going through time.” NOSFERATU AT ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL St. Paul's Cathedral, in conjunction with a grant from Trinity Wall Street, invites you to the first annual screening of the 1922 German Expressionist black-and-white movie classic Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens on All Hallow's Eve: Sunday, October 31, 7:00 pm. This silent movie will be accompanied by Ivan Docenko at the Cathedral Organ. Please join us in the comfort of the Cathedral to watch this earliest screen adaptation of Bram Stoker's classic novel Dracula on the big screen. All are welcome to this family-friendly, free event. COMING UP IN THE FALL 2010 BUFFALO FILM SEMINARS XXI: October 26 Hal Ashby The Last Detail 1973 November 2 Bruce Beresford Tender Mercies 1983 November 9 Wim Wenders Wings of Desire 1987 November 16 Charles Crichton A Fish Called Wanda 1988 November 23 Joel & Ethan Coen The Big Lebowski 1998 November 30 Chan-wook Park Oldboy 2003 December 7 Deepa Mehta Water 2005 CONTACTS: ...email Diane Christian: engdc@buffalo.edu …email Bruce Jackson bjackson@buffalo.edu ...for the series schedule, annotations, links and updates: http://buffalofilmseminars.com ...to subscribe to the weekly email informational notes, send an email to addto list@buffalofilmseminars.com ....for cast and crew info on any film: http://imdb.com/ The Buffalo Film Seminars are presented by the Market Arcade Film & Arts Center and State University of New York at Buffalo with support from the Robert and Patricia Colby Foundation and the Buffalo News