The Death of Michael Corleone

advertisement

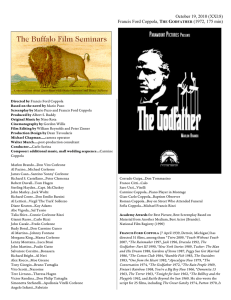

1 "The Death of Michael Corleone": A Re-­‐Appraisal of The Godfather Part III By Reece Crothers for The Seventh Art The Godfather currently ranks number 2 on AFI's top 100 films of all time. It was the highest grossing picture of its year. It was the recipient of Oscars for Best Picture; Best Actor, for Marlon Brando; and Best Adapted Screenplay, for Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo, who wrote the novel on which the film was based. It was nominated for another seven academy awards, including Best Supporting Actor for Al Pacino. Two years later, The Godfather Part II was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, once again earning Oscars for Best Picture and for Best Adapted Screenplay. Robert DeNiro won the Best Actor Oscar in the role originated by Marlon Brando in The Godfather. Coppola won for best director and joked: “I almost won this two years ago for the first half of the same picture!” Al Pacino was again nominated, this time as Best Actor, but lost to Art Carney for Harry & Tonto, Paul Mazursky's coming of old-­‐age picture about a retiree's road trip with his cat. In 1990, the American National Film Registry selected The Godfather for preservation in recognition of its cultural significance. Part II would be selected three years later for the same honour. 1990 also saw the release of The Godfather Part Three on Christmas Day. The Los Angeles Times dubbed it "the most anticipated film of the decade.” But the sixteen years between sequels had an affect on the academy's love affair with the Godfather series. Despite seven Academy Award nominations, Part Three did not win Best Picture like its predecessors. It did not win Best Adapted Screenplay. For the first time in the series, Al Pacino's performance wasn't even nominated. As of this recording, the film has yet to be selected by the National Film Registry for preservation for its cultural significance. Nowhere in popular culture has there been a more reverential discourse on the 2 Godfather films than in the HBO series "The Sopranos". Yet the pilot episode also mirrors the court of public opinion when it comes to Part Three, which Carmella Soprano succinctly sums up: “Part Three was like… what happened?" Indeed. Part Three is the Fredo of the trilogy: misunderstood, ignored... and murdered – at least in the press and nowhere more famously than Peter J Boyer's June 1990 Vanity Fair article, "Under the Gun". Boyer was highly critical of the film's various production problems and, in particular, Francis' casting his young and inexperienced daughter Sofia in the pivitol role of Mary Corleone. Even Janet Maslin's piece in the New York Times, which was favourable, echoed this sentiment. Maslin defended the film, stating, "Most film sequels are strictly optional. Godfather Part III is inevitable, and as such it's irresistable." But she too attacked Sofia's performance, writing: "Ms. Coppola, the director's daughter, gives a flat, uneasy performance that seriously damages Mary's role as the linchpin of this story." The fact that Sofia only took the role because Winona Ryder, who was previously cast as Mary, dropped out the day before she was to begin filming, garnered little sympathy for the young actress. Her father, meanwhile, was charged with reckless nepotism. Hal Hinson's Washington Post review seemed to sum up the immediate response to the film: "a failure of heartbreaking proportions." When Coppola was preparing the first Godfather, the book was not yet the phenomenon it would soon become. When the second film was released, the first Godfather had only been around for two years. But by the time Part Three was released, nearly two decades had passed. The Godfather films had become cultural institutions. How could Francis top One and Two? In the wake of such insurmountable expectations, Part Three was doomed to be a let down. But nearly twenty-­‐two years since its release, Part Three, is due for re-­‐appraisal. In the commentary track found on the film’s DVD release, Coppola offers 3 his explanation of exactly what happened and provides a convincing argument for the defense. First and foremost, this defense requires the viewer to imagine the film under a different title – one its authors preferred: The Death Of Michael Corleone. This rescues it from the perception that all three films are equal contributions to one, three-­‐part series, which the significant gap between production of two and three contradicts. There are precedents for considering Godfather films in alternate contexts than this, especially in viewing The Godfather and Part II as necessarily entwined. A four-­‐part television mini-­‐series that aired on NBC in 1977 that’s alternately referred to as The Godfather: A The Complete Novel for Television, which re-­‐imagined the first two pictures as one chronological narrative, doing away with the flashback structure of Part II. This re-­‐ editing of the first two parts was employed again, at a slightly reduced running time, for the video release, named The Godfather Saga. With this in mind, imagine if you will, the third picture not as The Godfather Part Three, a sequel to The Godfather and The Godfather Part II, but rather as an epilogue to The Godfather Saga, as Coppla and Puzo intended. Ironically, Coppola is to blame for the very concept of sequels titled with numerals. The first American picture to use this device was The Godfather Part II. Previously, the trend had been to give sequels independent titles, in order to avoid confusing audiences, who might presume they were being sold a product they had already purchased. The alternative would have been films like Bride Of Frankenstein, which included the original film’s title in their independent titles. Despite setting this trend, Coppola attributes his inability to convince the studio to accept his preferred title for Part Three as an example of his declining influence and power. The Coppola of 1990 was not the same man as the Coppola of 1974; a string of box office failures and personal tragedies, including the death 4 of his oldest child Gio, had humbled the man who had dominated the American cinema in the 1970s. Consider that he began the decade with the Oscar for co-­‐writing Patton, before writing and directing The Godfather in 1972, followed by The Conversation and The Godfather Part II in 1974 – for which he was nominated twice in the directing category, a feat unparalleled until Steven Soderbergh's nominations for Traffic and Erin Brokovitch twenty-­‐six years later. Coppola ended his run of classics with Apocalypse Now in 1979, a venture that he jests, "I never fully recovered from." When he finally accepted Paramount's offer to write and direct a third film in the now classic Godfather series, he was in no position to refuse. But as he had done throughout his career, he struggled over his obligations to deliver mainstream entertainment while looking to tell more intimate, personal dramas. And so, Michael Corleone once again serves as a mirror for his co-­‐creator in Part Three. Here we see an aging patriarch, full of regret, unable to escape his own history. Considering the film as The Death of Michael Corleone, it’s a haunting, heartbreaking tragedy – surprisingly tender in places and made by a much more mature filmmaker than the previous installments. It just wasn't the story audiences in 1990 wanted to see, the previous two films already canonized. They didn't want to see a diminished Michael Corleone, sick with diabetes, hair now grey and thinning. Interestingly, one of the greatest battles fought between Coppola and Paramount this time out, was indeed over Coppola's desire to cut Pacino's hair. As Coppola explains, as soon as he cut and dyed Pacino's hair, losing the thick, slick-­‐backed mane that had become iconic from the first two pictures, he announced to the audience that this was not the same virile, powerful Michael Corleone they had come to know. Coppola likens the act to cutting Samson's hair. 5 Rather than the unstoppable force of the first films – this established image – we have the Lear-­‐like figure with the steely grey brush cut. Indeed, consider Act Three, Scene Two of William Shakespeare's King Lear: “Blow, winds, and crack your cheecks! / Rage! Blow!” When Michael suffers from a stroke in Part Three, he exclaims, “Run at thunder, girl! Thunder can't hurt! Harmless noise!” Coppola, bored by violence as entertainment at this point, uninterested in "dreaming up new ways to kill somebody," dares to allow himself to be guided by Shakespeare in an attempt to deliver a deeper, richer drama. In addition to Michael as Lear, Talia Shire's Connie has transformed into something of a Lady MacBeth, steering the family towards more bloodshed with behind the scenes manipulations. Even the choice of the family's "bastard" son as the film’s protagonist over Sonny, Michael, or Connie's legitimate sons, is an explicit nod to Shakespeare. The villain Joey Zaza reminds us, “Mr. Corleone, all bastards are liars. Shakespeare wrote poems about that.” Apart from the influence of the Bard, Coppola and Puzo drew inspiration from the scandals surrounding the Vatican Bank and the death of Pope John Paul. It is interesting to note that the Vatican at one time owned Paramount Studios. This notable narrative thread, controversial at the time, prefigures Puzo's final novel, The Family, and the recent Showtime series concerning the Borgia family, but was not enough to draw attention away from the more personal and self-­‐referential Shakespearian elements to which audiences reacted so negatively. The story audiences wanted in 1990 was one that would have picked up from where Godfather Part II left off, the way the title suggests, repeating the formula of Michael as the always-­‐triumphant-­‐leader. It was the story written but never made: the rise of the Corleone family through the heroin and cocaine fueled 1970s and 80s. This was what Mario Puzo 6 referred to as "the good years when we killed everyone and no one killed us." The original Godfather film was originally intended to take place in the then-­‐contemporary 1970s, before Coppola's involvement and his insistence on returning to the novel's period setting, including Mr. Untouchable. Other versions of that seventies story were later developed without Coppola's involvement. In 1985, a version co-­‐written by Thomas Lee Wright included a character inspired by Mr. Untouchable, the notorious African-­‐American gangster Nicky Barnes, eventually played by Cuba Gooding Jr. in Ridley Scott's American Gangster in 2007. Wright's version was intended to star Eddie Murphy in the Nicky Barnes role and though it was never produced, it may very well have been the original source of what evolved into his screenplay for 1991's New Jack City, indicating a film that may have been more in line with what audiences expected. The film features Wesley Snipes in the Nicky Barnes role and in the original Godfather tradition, includes a climactic sequence that sees parallel events culminate in the eruption of violence during a family social ceremony, here a wedding – all woven together through music. Additionally, 90's R&B star Keith Sweat plays a Johnny Fontane-­‐esque role – Fontane notably appearing in all three Godfathers. The parallels to Godfather even extend to Part Three. Consider the similarities in New Jack City’s church steps shootout with the killing of Mary Corleone on the Opera House steps in the climax to The Death of Michael Corleone. The scene in which Snipes takes his vengeance against the Italian gangsters responsible for the church steps shootout seems very much like a hold-­‐out from the alternate Godfather III script, as does one exchange between Snipes and Ice T, which echoes the dialogue and themes from the Godfather films. In 1990, another film that satisfied the audience's appetites and expectations that Part Three did not was made by the director that Francis Coppola had tapped to helm Part 7 II before the studio rejected the idea: Martin Scorsese. Nominated for Best Picture that year alongside the third Godfather, the film was Goodfellas. Goodfellas was the propulsive, highly kinetic, wildly funny and explosively violent mob picture – complete with a 70s rock soundtrack in line with the expectations of a generation of viewers who grew up with the Godfather franchise. The film even fills in a missing chapter in the cinematic chronicle of America's mafia history between Godfather parts II and III. We see this desire for different periods of the mob filled in on screen in a number of other films beginning around this time. 1990's State of Grace gives us the Irish mob of 1980's Hell's Kitchen, as written about in T.J. English's excellent non-­‐fiction book The Westies. Other notable post-­‐Godfather-­‐Three pictures, like the period-­‐set dramas Bugsy, Casino or Donnie Brasco. More contemporary in production and setting is the six seasons of The Sopranos, which paved the way for the prohibition-­‐era Boardwalk Empire. These and others complete the missing story, as if all of these films and series are in dialogue with one another since they all, along with the Godfather series, draw from the same well: the true stories and legends of America's underworld history. It is as if they all occupy the same universe. There was almost a fourth Godfather film set up in 1999, in the midst of these films, which might have satiated the audience's desire to see those types of stories through the eyes of the Corleones. It would have featured a parallel structure like Part II that would show Leonardo DiCaprio as a young Sonny Corleone, intercut with Andy Garcia becoming a Gotti-­‐like 1980s mob boss. This again would have been more in line with audience expectations, all having learned from the mistakes of Part Three. And yet these films that have come out after Godfather Part Three are precisely what allow us, twenty-­‐two years later, to forget whatever criticisms that were levelled against 8 the third Godfather picture at the time – they fulfill the expectation that was disappointed at that time. We can now judge it not for the film it isn't, but for the film it is – the great qualities it has as a singular film that comments back on the first two, but is not beholden to the purposes they served. Take, for instance, the most hated element: Sofia Coppola’s performance. What is most striking today about the much maligned Sofia Coppola performance in particular is the heartbreaking vulnerability of a young woman on the precipice of adulthood – not yet grown into herself – that permeates all of her scenes. In the years since she played Mary Corleone, Sofia has become an accomplished artist, a critical darling even, as a writer and director in her own right, a Best Screenplay Oscar winner for her much loved Lost in Translation. The question of whether or not she earned the role of Mary Corleone is no longer relevant and we can instead see what she accomplishes having grown accustomed to her. Though her California accent is a little distracting, we need only watch her eyes to see the value in her performance. It is, as Francis says, "an extremely truthful" performance. And is there anything so tender in any other Godfather picture as the doomed romance that develops between Mary and her cousin Vincent, as played by Andy Garcia? Indeed, for this reason Sofia's death scene on the Opera House steps is arguably the most devastating of all the Godfather deaths, if for no other reason than Mary is the family's innocent one. The bullets intended for her father parallel the abuse she received in the media at the time, which was meant to injure her father and director. As Francis has said: "There is no worse way to pay for your sins than to have your children included in your punishment." Lost in these public condemnations is Andy Garcia's performance as the bastard son, Vincent Mancini, which is one of the franchise's greatest assets. He pulls off a remarkable 9 feat, as he embodies the best and worst of the Corleones who came before him: Sonny's brash temper, Michael's calculating cold bloodedness, and Vito's polished, graceful swagger and charisma – often, as in this scene, all at the same time. This again comments back on the series, though recognizing, through the new actor, the distance from that singular story in The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. This commentary is at its most clear during what is, perhaps, one of the most exciting sequences in any of the three pictures: the climactic half-­‐hour that interweaves multiple assassination attempts and double crosses with the production of Petro Mascagni's opera "Cavallaria Rusticana" featuring Michael's son, Anthony, in the lead. Coppola has said that everything about the Godfather films, symbols, themes, characters, and narrative, are rooted in that opera and this is the film that lays this construct bare. It takes what was has existed in the previous two parts and draws attention to its source. Consider the procession that recalls the killing of Fanucci during the festa in Part II. Furthermore, the depiction of biting off an enemy's ear in the opera harkens back to the earlier scene with Vincent and Joey Zaza in which he bites Zaza's ear – we are seeing the influence in the very same film, which is, from a distance, commenting on the first two parts. Ironically, it is Mary whose death ends this significant sequence, because to kill Michael here was not enough punishment in Coppola's estimation. Having learned first hand the pain of losing your own child, Coppola inflicts the most severe punishment imaginable to his alter ego, the murder of his child, which illustrates to what degree this film is a reflection of Coppola’s own life more than a strict continuation of the first two films. To pay for the sin of killing his brother Fredo, Michael loses Mary. Death would only find Michael some time later, an ironically peaceful passing of a man who has caused and known so much suffering and bloodshed in 10 his life, which befits the length of time that separates Part Three from the closely intertwined first two parts. For Michael Corleone, death alone is no punishment. It only marks the end of his tragedy – an epilogue to the Saga. Godfather Part Three may be a disappointing sequel to a series of two films that are basically one, but as The Death of Michael Corleone, it is a fitting epilogue to one of the greatest single film of all time – the collected Godfather Saga – and a worthy addition to the canon of American crime classics.