Riccardo Muti Conductor David McGill Bassoon Schubert Symphony

advertisement

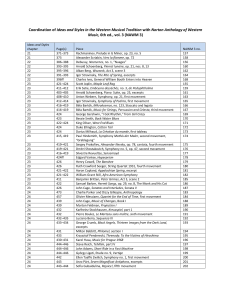

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-THIRD SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, June 12, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, June 13, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, June 14, 2014, at 8:00 Tuesday, June 17, 2014, at 7:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor David McGill Bassoon Schubert Symphony No. 6 in C Major, D. 589 Adagio Andante Scherzo Allegro moderato Mozart Bassoon Concerto in B-flat Major, K. 191 Allegro Andante ma adagio Rondo: Tempo di menuetto DAVID McGILL INTERMISSION Schubert Symphony No. 1 in D Major, D. 82 Adagio—Allegro vivace Andante Allegro Allegro vivace This series is made possible by the Juli Grainger Endowment. Sponsorship of the music director and related programs is provided in part by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to 93XRT, RedEye, and Metromix for their generous support as media sponsors of the Classic Encounter series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Franz Schubert Born January 31, 1797, Himmelpfortgrund, northwest of Vienna, Austria. Died November 19, 1828, Vienna, Austria. Symphony No. 6 in C Major, D. 589 Symphony No. 1 in D Major, D. 82 Schubert’s contemporaries—even the few who understood the magnitude of his talent—did not think of him as a composer of symphonies. Antonio Salieri, who was one of his first teachers and a man who knew the Viennese music scene as well as anyone in the early years of the nineteenth century, called Schubert a genius, and said that “he can write anything: songs, masses, string quartets . . . ,” but he failed even to mention the symphony. Not one of the eight symphonies by Schubert that Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony perform this season was publicly known during the composer’s lifetime. Most of them weren’t even published until the very end of the nineteenth century, more than fifty years after Schubert’s death. In 1894, while Antonín Dvořák was living in the United States, he wrote an article for The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, considering the reasons Schubert “made his way so slowly to popular appreciation,” and why the symphonies, in particular, did not gain the immediate admiration of those by other composers. “He was young, modest, and unknown,” Dvořák writes, “and musicians did not hesitate to slight a symphony which they would have felt bound to study, had it borne the name of Beethoven or Mozart.” The comparison with Beethoven is both inevitable and misleading. Schubert and Beethoven were composing symphonies at the same time in Vienna during the first years of the nineteenth century—never once meeting nor even crossing paths until the very end of Beethoven’s life. Each of Beethoven’s symphonies was premiered to considerable fanfare in one of Vienna’s main public theaters within a year or so of its completion. 2 Schubert’s were privately performed in the same city and quickly forgotten. All nine of Beethoven’s symphonies were published during his lifetime; not one piece of Schubert’s orchestral music appeared in print during his. And yet, for all his apparent lack of public success with the form, Schubert persisted. He started more symphonies than Beethoven and finished nearly as many—all in a shorter period of time. (While Beethoven composed his nine over the span of twenty-five years, Schubert completed seven and left another six unfinished in just seventeen years.) Schubert was working on his newest one—the so-called Symphony no. 10—at the time of his death. (In 1995, the Chicago Symphony performed Luciano Berio’s haunting and imaginative Rendering, which is based on Schubert’s sketches for this symphony.) For Dvořák, writing in 1894, Schubert’s first six symphonies were recent discoveries, as they were for all musicians in the late nineteenth century. (They were published for the first time in 1884 and 1885.) He had recently begun to conduct the symphonies and he highly recommended them to others. “The more I study them,” Dvořák concluded, “the more I marvel.” Written in little more than four years—from sometime in 1813 to February of 1818—they are among the most impressive and substantial of Schubert’s so-called early works (although, as Donald Tovey pointed out long ago, “every work Schubert left us is an early work”). They are so refined and assured that it is difficult to remember that they are the works of a teenage boy. Schubert’s early symphonies come from the busiest time of his life. He was still a schoolmaster then, a prisoner of the classroom who fi lled his free time writing the music that would one day make him famous. Not all this music is important or memorable; Schubert must have been writing at breakneck speed and often well into the night. But much of it is unusually impressive regardless of the circumstances, and some of the songs, in particular, are among his finest works—they reveal a gift too strong and an imagination too vivid to be stifled even by the dull rigor of drilling reluctant boys. Symphony No. 6 in C Major, D. 589 I n November of 1816, the Italian Opera Company made its first visit to the great music capital of Vienna, bringing with it Rossini’s Tancredi and L’inganno felice. This was Vienna’s first taste of Rossini’s operas, and soon the city’s large musical public, including the nineteen-year-old Franz Schubert, could not get enough of this intoxicating music. Word of Rossini’s recent extraordinary successes in Italy had sent shock waves through the musical establishment in Germany and Austria—he had first drawn international attention in 1813 with the serious Tancredi and the comedy, L’italiana in Algeri. In the home of the great classical masters, his music had quickly been condemned: “He could have become one of the most outstanding vocal composers of our time,” wrote the composer Ludwig Spohr, “if he had been methodically instructed in Germany and guided on the one true path through means of Mozart’s classical masterworks.” Schubert went to hear Tancredi and left the theater enraptured. “You cannot deny that he has extraordinary genius,” he wrote to his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner. “The orchestration is highly original at times, and occasionally so is the vocal writing . . . .” In the thrall of the new Rossini rage sweeping Vienna, Schubert composed two overtures “in the Italian style,” trying out a new way of writing that immediately changed his own. Schubert’s Sixth Symphony is the main beneficiary of his discovery of Rossini’s COMPOSED October 1817–February 1818 FIRST PERFORMANCE December 14, 1828; Vienna, Austria FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES February 7 & 8, 1957, Orchestra Hall. Sir Thomas Beecham conducting music. Yet, for all the ways the great Italian composer’s music enlivened and enriched Schubert’s orchestral writing, by 1817, with several symphonies already completed, Schubert had become an assured symphonic composer with a voice of his own. One can still pinpoint influences and cross-references—a Mozartean introduction to open the score, the Haydn-like touch of beginning the allegro with the winds alone, the instrumental fireworks of Rossini through the movement, a speeded-up coda that echoes the effect of Rossini’s signature windup crescendos. The third movement, the first in Schubert’s output to be labeled a scherzo, resembles Beethoven’s in its power and thrust. But more revealing are gestures and ideas, particularly in the finale, that are the seeds of the other C major symphony to come—the one that would eventually be called Great to distinguish it from this somewhat slighter one in the same key. With the Sixth Symphony, we find Schubert steeped in the conventions of the classical symphony, but striving to break free and forge his own path, as only the greatest of symphony composers can. It is a work of consolidation, but more importantly, one of anticipation. After completing this score in February of 1818, Schubert began and abandoned several symphonies, including the one we now know as the Unfinished. But it would be another decade before he would actually finish one last symphony. MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES January 26, 27 & 31, 1995, Orchestra Hall. Zubin Mehta conducting INSTRUMENTATION two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 28 minutes CSO RECORDING 1979. Sir Georg Solti conducting. EuroArts (video) 3 Symphony No. 1 in D Major, D. 82 S chubert knew the orchestra from the inside—he began playing in the student ensemble of Vienna’s Imperial and Royal City College at the age of twelve—and we might well guess from listening to his Symphony no. 1 that closes this concert that, as an orchestral musician, he regularly played symphonies by Haydn and Mozart as well the first two by Beethoven. Schubert enjoyed the luxury of hearing his own First Symphony played by this same ensemble—an invaluable experience for a young composer (he was just sixteen at the time) still getting accustomed to matching the music in his head with the reality A sketch of Vienna of how it sounded in performance. Schubert never heard his First Symphony again during his lifetime; decades passed, in fact, before it was introduced to the public. It was the last of Schubert’s symphonies to be played by the Chicago Symphony in Orchestra Hall, in 1982, more than ninety years after the CSO’s founding—and it has not been played by our orchestra since. Mozart and Haydn may have been his inheritance, and Beethoven an irresistible contemporary influence, but, from the start, Schubert was eager to strike out on his own. The blueprint of Schubert’s Symphony no. 1 in D major follows the great classical model of Haydn’s last London Symphonies in its scoring and broad outlines, with a grand slow introduction to the opening allegro and a light, almost breathless finale. Schubert even “borrows” Beethoven’s Prometheus theme in his first movement—a rare admission of the other Viennese master’s influence. But, as Dvořák pointed out, “Schubert’s musical individuality is unmistakable in the character of the COMPOSED Completed by October 1813 FIRST PERFORMANCE date unknown 4 melody, the harmonic progressions, and in many exquisite bits of orchestration.” In other words, Schubert already sounded like Schubert, even in a work as early as his First Symphony (it is only number 82 in Otto Erich Deutsch’s comprehensive catalog of 998 compositions). The teenage Schubert was unafraid to put his own stamp on the symphonic design that Haydn had perfected in his sixties. Against convention, Schubert brings back his Adagio introduction in the body of the Allegro music that follows (Schubert does not slow the tempo, but merely incorporates the gist of his opening material into the flow of faster music). The entire first movement has a kind of coltish energy that carries to the rousing final measures, with their uncommonly high trumpet lines. Schubert apparently had second thoughts about his extended adaptation of Beethoven’s Prometheus tune, and he later cut an entire passage just before the development section. Clearly, for all his early mastery of smaller forms such as the song, he was already beginning to think in large architectural terms, like a true symphonist. Schubert’s slow movement, spacious and not surprisingly songful, shares much, in spirit and in detail, with the corresponding movement in the Prague Symphony, Schubert’s favorite of the Mozart symphonies. The third movement is an old-school minuet and trio. Although Schubert stays in D major throughout, he achieves a surprising sense of variety in this most rigid of forms by shifting orchestral colors even as the music repeats. The finale is brisk and effective, with subtle reference to thematic material in the opening movement that cannot be explained merely as natural family resemblance. FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES August 16, 1974, Ravinia Festival. David Zinman conducting January 7, 8 & 9, 1982, Orchestra Hall. Dennis Russell Davies conducting INSTRUMENTATION one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 29 minutes SCHUBERT’S SYMPHONIES: FROM THE SKETCHED AND UNFINISHED TO THE NUMBERED AND COMPLETE F only in sketches and was left incomplete at the rom sometime around 1811 until his death seventeen years later, Franz Schubert began composer’s death, has been reconstructed by other hands and published as no. 10. Here is the at least thirteen symphonies. This season, Riccardo Muti and the CSO will play the eight that have come down to us in performable condition, including one famous symphony, known as no. 8, that is itself unfinished. The numbering of Schubert’s symphonies has long presented quandaries. Although Schubert sketched Symphony no. 7 in full, he never orchestrated the score, and it is therefore unplayable (except as orchestrated by others). As a result, some scholars have proposed Gustav Klimt. Schubert at the Piano, oil on canvas, 1899 renumbering symphonies nos. 8 and 9 and as nos. 7 and 8, respectively. (The suggestion has rundown of all of Schubert’s symphonic attempts not caught on; the CSO sticks to the original that survive, with the standard catalog numbers numbering.) A final symphony, which exists assigned by Otto Erich Deutsch in 1951. —P.H. Symphony, D major. First movement only. ?1811 D. 2b Symphony No. 1. D major Completed by October 1813 D. 82 Symphony No. 2. B-flat major December 1814–March 1815 D. 125 Symphony No. 3. D major May–July 1815 D. 200 Symphony No. 4. C minor. (Tragic) Completed by April 1816 D. 417 Symphony No. 5. B-flat major September–October 1816 D. 485 Symphony No. 6. C major. [Sometimes known as the Little C major] October 1817–February 1818 D. 589 Symphony. D major. Two movements in piano sketch May 1818 D. 615 Symphony. D major. Sketches After 1820 D. 708a Symphony No. 7. E major. Sketched in score; not orchestrated August 1821 D. 729 Symphony No. 8. B minor. (Unfinished) October 1822 D. 759 Symphony No. 9. C major. (Great) 1825–1828 D. 944 Symphony. D major. [Sometimes known as no. 10]. Sketches mid-1828 D. 936a 5 Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Bassoon Concerto in B-flat Major, K. 191 Although Mozart may have written as many as five bassoon concertos, this is the only one that has survived. It is the earliest of all Mozart’s concertos for wind instruments, and, despite the fact that it is the work of an adolescent, this is a little masterpiece. The score is contemporary with Mozart’s first piano concerto, in D major, and his first violin concertos—all products of the mid1770s. These are works that show Mozart fully engaged in putting his own stamp on traditional forms and procedures; he is no longer an apprentice—even one with the most astonishing gifts—but a man establishing his own practice. Mozart would never quit learning, borrowing, and assimilating what he picked up in the musical world at large, but the process of transforming and personalizing had already begun. Even though the bassoon was not a common solo instrument at the time, the main thematic material of this concerto was carefully designed expressly for the instrument, showcasing its unique qualities and disguising its limitations in power and range. In this piece, Mozart has already moved beyond mastering the general demands of concerto form to deal, in very COMPOSED 1774 FIRST PERFORMANCE date unknown FIRST CSO PERFORMANCE November 10, 1956, Orchestra Hall. Leonard Sharrow as soloist, Fritz Reiner conducting © 2014 Chicago Symphony Orchestra 6 specific and creative ways, with the individual needs of his client. Mozart often wrote music for performer-friends, but we cannot be certain for whom this concerto was intended. There are several possible candidates, including two bassoonists employed by the archbishop of Salzburg at the time, as well as Thaddäus von Dürnitz, an amateur bassoonist from Munich who apparently had commissioned bassoon works from several composers, including Mozart. The first movement highlights the bassoon’s many virtues, including its extraordinary agility and the ability to trill, leap (nearly two octaves in this case), repeat notes rapid-fire, sing lyrically, and sit comfortably on prominent low notes. The interaction with the orchestra is lively and conversational, not that of a star performer with its supporting cast. The second movement is a dreamy aria, with an elaborately embroidered melody over muted strings—an early essay in the mood of the Countess’s “Porgi amor” from The Marriage of Figaro. The finale is a minuet—not music designed for the ballroom, but based on the lilting rhythms of the standard courtly dance. Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES December 1, 2 & 3, 2011, Orchestra Hall. David McGill as soloist, Jaap van Zweden conducting INSTRUMENTATION solo bassoon, two oboes, two horns, strings CADENZAS David McGill APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 18 minutes CSO RECORDING 1984. Willard Elliot as soloist, Claudio Abbado conducting. Deutsche Grammophon