Laboratory Animal Care Workforce Study

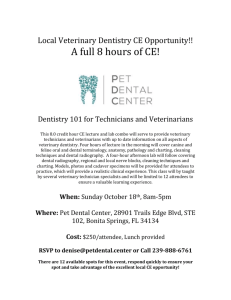

advertisement