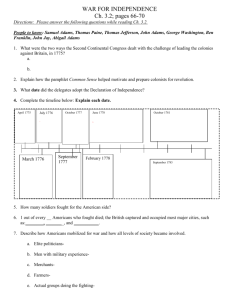

John Adams: Pioneer American Conservative

advertisement

John Adams: Pioneer American Conservative A. Owen Aldridge DR.BENJAMIN RUSH,one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, once called John Adams and Thomas Jefferson “the North and South Poles of the American Revolution.”’ This observation places Adams at the head of the conservative ranks in the early years of the republic and Jefferson as the leader of the contrary liberal current. Paradoxically, however, the private lives of the two statesmen almost entirely reverse these positions. Jefferson, a member of the landed aristocracy of Virginia, owned slaves throughout his entire life and surrounded himself with every available comfort and luxury. Adams, although by no means plebeian, was descended from sturdy New England settlers, worked on his own farm, and lived frugally even while serving as a diplomat in Paris and as president in Washington. Adams himself noted t h a t Jefferson was generally regarded as “eternally in opposition to government, and myself constantly in favor of it.”2Today, of course, it is the conservative attitude that is associated with opposition to big government. Adams and Jefferson, however, thought alike on many political, aesthetic, and moral issues from the time of their collaboration on the Declaration AOWEN .&<RIDGE isprofessorEmeritus in the comparative literature program at the Unioersity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. of Independence to the moment of their deaths on the same day in 1826. Many of the differences between the two leaders and the popular belief that these differences were extreme came about because of political party divisions. Both were Federalists in the original meaning of the word as comprising merely support of colonial independence. Both were republicans, however, in their opposition to monarchy during the framing of the Constitution. But when the Republicans became a party favoring the French Revolution, Jefferson became an ardent adherent while Adams remained in the Federalist fold. Later in his life Adams regretted that they should have been “separated by mere differences of opinion in politics, religion, philosophy, or anything else.”3 George Washington and Alexander Hamilton are sometimes seen as rivaling Adams for the title of preeminent American conservative, but each comes far short of Adams in qualifications. Washington wrote very little and did not expound a formal political philosophy of any kind. Hamilton was more of a pragmatist than a theorist, influenced by contemporary conditions rather than ideology, and his activities were chronologically subsequent to those of Adams. Russell Kirk also places Hamilton in a different class from Adams, describing 217 Modern Age LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED him as “thefirst American businessman” in contrast t o Adams as “the founder of true conservatism in A m e r i ~ a . ”Kirk ~ is not stinting in his praise, affirming that Adams’s “body of political thought exceeds, both in bulk and penctratim, any other work on government by an American.” Strangely enough, Irving Babbitt in his Democracy and Leadership (1924) extols Washington, but has littletosayabout Adams. He does quote as an epigraph, however, from a letter from Adams to Jefferson, 15 November 1815, a passage formulating “the fundamental article” of his political creed that “despotism or unlimited sovereignty or absolute power is the same in a majority of a popular assembly, an aristocratical council, an oligarchical junto, and asingle emperorequally arbitrary, cruel, bloody and in every way diabolical.” The word conseruative derives from a verb meaning to keep, t o retain. A political conservative is usually considered one who advocates a political system based upon a constitution or a collection of laws designed t o provide legal equality for every citizen. A social conservative must ideallyreveal acapacity for compromise and maintain an intelligent interest in human affairs other than finance and politics. Of equal importance, he must adhere toaprivatecodeof behavior based on high ethical standards, standards based in large measure on a knowledge of the historical and literary bulwarks of his culture. In Adams’s society, these foundations were considered to reside in their purest formamong the classics of ancient Greece and Rome. From the days of his youth, Adams acquired a thorough foundation in this heritage, basing upon it a considerable amount of his political theory. He also engaged in exemplary moral conduct throughout his entire life, earnng the enviable cognomen of “Honest John Adams.” As a young student, wavering between law and divinity as prospective careers,’ he maintained that the most important objective in life is not money, honor, political office,or scientific knowledge, but “Habits of Piety and Virtue.” He resolved to study thescriptures four nights weekly and a Latin author on the other three.6In later life,he expounded the view that for humanity at large the quest for honor surmounts any other motivation. From youth to old age, Adams found inspiration and respite in reading, includingclassics such as Homer, Virgil, Horace and Cicero.If hewereascholar, heaffirmed, he would have read military Consequently in a letter to a general of the Revolution, he cited a host of examples from ancient Greek history to support his opinion “that Courage and reading were all that were necessary to the formation of an Officer.’18In the early years of the republic he envisioned the establishment of an academy for the “improving and ascertaining of the English language.” The example of Greece and Rome, he believed, “would be sufficient, without any other argument, to show the United States the importance to their liberty, prosperity, and glory of an early attention to the subject of eloquence and language.” He accurately predicted that English in the next and succeeding centuries would be “moregenerally the language of the world than Latin was in the last or French is in the present age.”9 In one of his earliest published works, Thoughts on Government (1776), Adams declared, “All sober inquiries after truth, Pagan and Christian, have declared that the happiness of man, as well as his dignity, consists in virtue.’”O In connection with the same work, h e wrote to a friend, “I hold the Principle of Honour Sacredbut am not ashamed to Confess myself so much of a Grecian, or Roman, if not of a Christian as to think the Principle of Virtue of higher Rank in the Scale of moral Excellence, than Honour.”” In the same spirit Adams observed in his diary, 28 April 1756,that themost important objecSummer2002 218 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED I tive in life is not money, honor, political office, or scientific knowledge, but “Habits of Piety and Virtue.” The meanest of men who endeavor to promote the happiness of their fellow men should be esteemed higher than the greatest magistrate who works for his own pleasure or ambition.I2Adams drew no line between social and private virtue, considering them parts of the same quality. In remarks instigated by the death of his mother-in-law, he maintained that both natural morality and Christian benevolence “make it our indispensable Duty to lay ourselves out, to serve our fellow Creatures to the Utmost of our Power of promotingand supporting those great Political systems, and general Regulations upon which the Happiness of Multitudes depends.”l3To one of his relatives, aminister who had assured him that God would impart wisdom and guidance for “Establishingthe Liberties of America on a perpetual basis,”Adams replied that political liberty depends not upon God, but upon the religion and morality of the populace. “The only foundation of a free Constitution, is pure Virtue, and if this cannot be inspired into our people, in a greater Measure than they have it now, they may change their Rulers, and the forms of Government, but they will not obtain a lasting Liberty.”14 Translating the Latin adage Omnium Rerum Domina Virtus, “Virtue is the Mistress of allThings,”Adams reasoned in his diary that “a Nation that should never do wrong must necessarily govern t h e World.”I5He added that the power of virtue is unfortunately not a very common topic. One of the advantages of Christianity, heperceived, is bringing the principle of loving your neighbor as yourself to the attention andvenerationof theentirepopulace so that “Children, Servants, Women and Men are all Professors in the science of public as well as private Morality.” Adams’s most sensitive comment on virtue consists of a profession in his mem- oirs of his own sexual purity. “NoVirginor Matron ever had Cause of Grief or Resentment for any Intercourse between me and any Daughter, Sister, Mother, or any other Relation of the Female Sex. My Children may be assured that no illegitimate Brother or Sister exists or ever existed.”16 Not all leaders of the Revolution were able to make such a declaration. That of Adams has never been contested. Since Adams began public life as a lawyer, it is not strange that the title of his first major publication A Dissertation on Canon and Feudal Law (1765), should reflect legal terminology, although the content of the workitself deals primarily with the principles of liberty and freedom in America. These are contrasted with “the twogreatest systems of tyranny”that have grown out of Christianity, feudalism, which tied serfs to the land, and priestcraft, which harnessed a people’s minds. The temporal grandees and the spiritual grandees collaborated with each other to obtain a blind and implicit obedience to both systems. Neither the theme nor the content of the Dissertation may properly be labelled as either primarily conservative or liberal, even though Adams observed that the “poor people” have seldom had an opportunity to defend their rights, “Rightsthat cannot be repealed or restrained by human law^.''^' Contrary to the servile belief imposed upon the common people by the twin tyrannical systems of feudalism and priestcraft, “government is a plain, simple, intelligent thing, founded in nature and reason, quite comprehensible by common sense.” Reminding his readers that so-called “British liberties are not the grants of princes or parliaments,” Adams described the struggles and sufferings of the early settlers in New England. “Let us recollect it was liberty! the hope of liberty,forthemselvesandus andours, which conquered all discouragements, dangers, and trials.”But libertywas not to beeither obtained or preserved without educa- Modern Age 219 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED I tion, without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right to knowledge from the frame of their nature. Revealing his personal devotion to history and the classics, Adams urged, “Let us study the law of nature; search into the spirit of the British constitution; read the histories of ancient sages; contemplate the great examples of Greece and Rome; set before us, the conduct of our own British ancestors, who have defended for us the inherent rights of man against foreign and domestic tyrants and usurpers.” Adams’s earliest publication placing him squarely on the side of conservatism, Thoughts on Gouemment (1 776), came as the result of three Southern gentlemen shortly after the Declaration of Independence asking for advice on drafting constitutions for their colonies. Although the main thrust of his argument was levelled against the concept of a single legislature as advocated by Thomas Paine in Common Sense, Adams also stressed the merits of keepingseparatethelegislative, executive, and judicial powers, an arrangement that was by no means universally accepted at the time. He differed from Paine on both the form of the legislatureand the division of powers, particularly on the former, charging that Paine’s “crude,ignorant Notions of aGovernment by one Assembly, will do more Mischief, in dividing the Friends of Liberty, than all the Tory Writers. He is a keen Writer, but very ignorant of the Science of Government.”Is Adams introduced his own views by means of a generally accepted principle, although one more frequently expressed by liberals than by conservatives: “the form of government which communicates ease, comfort, security, or in one word happiness to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best.”lg He immediately joined this principle, however, with a highly conservative one-the form of government that best promotes happiness is that “whose principle and foundation is virtue.” In government, he added, ‘‘apeople cannot be long free, and never can be happy, whose laws are made, executed, and interpreted by one assembly.” He opposed a single legislative assembly on the grounds that it is “liable to all the vices, follies and frailties of an individua1,”is“aptto be avaricious,and likely to grow ambitious and eventually vote itself perpetual.”20To avoid these hazards, Adams advocated the election of two distinct representative bodies each operating to check and to arrest the errors of the other. He also proposed that the governor be elected by both houses and be given a negative upon the legislature. Recognizing the importance of the judicial power, Adams affirmed that it should be separate and independent of both the legislative and the executive powers so that it could be a checkon both and they a check upon it. Paine in a further pamphlet, Four Letters on Interesting Subjects (1776), published shortly after Adams’s Thoughts on Gouernment,objected to both of Adams’s principles.21Two houses, he affirmed,“may fall out about forms and precedence, and check one another’s honour and tempers, and thereby produce petulance and ill-will, which a more simple form of government would have prevented.” On the subject of the separation of powers, Paine argued that onlytwoexist in government, “the power to make laws and the power to execute them; for the judicial power is only a branch of the executive, the CHIEF of every country being the first magistrate.” The two opposing conservative measures of a bicameral legislature and an independent judiciary upheld by Adams, however,were later incorporated in the Constitution of the United States and that of a bicameral legislature became the focus of his most significant publication, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the Unitedstates of Summer 2002 220 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED America (1787). Adams was also largelyresponsible for the provision for two houses in the Constitution of Massachusetts. Although present in the convention for drawing up the document for only the months of September and October 1778,he was acknowledged as its “principal engineer.”22 It clearly and succinctly states Adams’s doctrines: “the legislative, executive and judicial power shall be placed in separate departments, to the end that it might be a government of laws, and not of men,” and the legislative department “shall be formed by two branches, A SENATE and HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.” Before this constitution was formally adopted, Adams was sent by the Continental Congress to represent the colonies in a treaty of peace in Paris, where he met two of the major French writers on political theory, Anne-Robert Turgot and Gabriel Bonnot de Mably. The latter, soon after making Adams’s acquaintance, conceived the notion of writing a history of t h e American Revolution and approached him for advice and assistance. Instead of encouragement, however, Mably received a blunt written disparagement of his project on thegrounds that he lacked both time and research facilities for a work of such magnitude. As a result, Mably abandoned his ambitious enterprise, but wroteand published in its stead Observationson the GovemmentandLaws of the United States o f America (1784), based almost entirely on the state constitutions that were then being circulated throughout France, largely through the efforts of Benjamin Franklin. In his text Mably several times affirmed that Adams had asked him to write on the topic of the American constitutions. Although Adams was offered the opportunity of denying these assertions, he declined to do so on the grounds of not wishing to enter “into the Fracasseries of the Men of Letters in F r a n ~ e . ” ~1787 ~ I n he proceeded to do just that, however, by publishing two volumes of A Defence o f the Constitutions o f the Governmentofthe UnitedstatesofAmerica and a third volume in the next year specifying on the title page Against the Attack ofM. Tuigot. Adams almost certainly had Mably in mind when he began writing, but shifted his attention to Turgot when Richard Price in England published in 1784Observations on the American Revolution, including in his appendix a letter from Turgot written in 1778 indicating dissatisfaction with every one of the state cons t i t u t i o n ~ .Adams ~~ may have added Turgot to his title as a ploy to attract increased European readership even though the text of the Defence gives the French statesman only incidental treatment. Inaletterto Jefferson in 1787,Adams argues that his Defence is a refutation of Turgot: The two volumes [ 1&2,1787] are confined to one point, and if a City is defended from an attack made on the North Gate,it may be called a Defence of the City, although the otherthreeGates, theEast, West andSouth Gates were so weak as to have been defenceless, if they had been attacked.-If aWarrior should ariseto attackour Constitutions where they are not defensible, 1’11 not undertake to defend them. Two thirds of our States have made Constitutions, in no respect better than those of the Italian Republicks,andassureas thereisanHeaven andanEarth, if theyarenot altered theywill produce Disorder and Conf~sion.2~ According to this metaphor, thesingle gate that needed to be defended against Turgot was that of a legislature of two houses and vindicating it was equivalent to defending the constitutions of all the states. In his text Adams posed the “great question” as “What combination of powers in society, or what form of government, will compel the formation, impartial execution, and faithful interpretation of good and equal laws, so that the citizens may constantly enjoy the benefit of them, and may be sure of their 221 Modem Age LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED continuance?”26Adams does not, however, give a clear idea of Turgot’s ideal state and how it differs from his own. The main issue is not the same as that in Thoughts on Government in which both sides accept a separation between executive and legislative powers and differ merely over whether the latter should be vested in one or in two houses. Turgot had in mind a single assembly-conceived as the nation in which all three powers were united. In his preface, Adams affirms that “M. Turgot intended that an assembly of representatives should be chosen by the nation, and vested with all the powers of government; and that his assembly should be the centre in which all the authority was to be collected, and should virtually be deemed the nation.” Although Adams maintains that the rest of his book is devoted to explaining the consequences of this idea and collecting opposing authorities, in reality it consists almost entirely of a historical survey of systems of government in which are found elements favorable to his own scheme. Here he draws upon his previous study of history, both ancient and modern, citing Herodotus,Thucydides, Diodorus Siculus, as well as Machiavelli, Harrington, and Hume. In explaining his motive for writing, he includes an extensive Latin quotation from Cicero containing the latter’s famous sentence “Respublicaest res populi.” Comparing the three branches of government to the treble, tenor, and bass in music, he opposes the placing of unlimited power exclusively in the hands of any one of the three.27He also cites theTeutonicsystem described by Tacitus and Caesar to illustrate the evils of attempting to mix “the authority of the one, the few, and the many, confusedly in one assembly.” In a single house it would be impossible to maintain equal virtue among its representatives, who would cluster by nature into groups or divisions based upon vir- tue, experience, education or envy.28 The largest part of the Defence is devoted to separate chapters describing past republics in Italyand elsewhere. In a chapter on the opinion of philosophers, he includes a treatment of Franklin, who, while ambassador in Paris, had been closely associated with Turgot. In his private correspondence Adams affirms that it was under Franklin’s influence that Turgot had come to admire the Constitution of Pennsylvania with its single legis1atu1-e.~~ His Defence admits that he does not know all the details of Turgot’s system, but presumes that he did not favor a simple monarchy or aristocracy, but rather a single house representing all the people and that, according to “the most benign construction,”the representatives would be chosen annually.30 Adams knew even less about Franklin’s system and even that knowledge was based upon general reports indicating that Franklin had presided over the convention that had drawn up the Pennsylvaniaconstitution that provided for asingle legislature. Beyond this Adams was aware only of the widely circulated report that Franklin had said in the convention that “two assemblies appeared to him like a practice he had somewhere seen, of certain wagoners, who when about to descendasteephillwithaheavyload,ifthey had four cattle, took off one pair from before, and chaining them t o the hinder part of the wagon drove them up hill; while the pair before and the weight of the load, overbalancing the strength of those behind, drew them slowly and moderately down the hill.” Adams’s summary of Franklin’s illustration is completely different from one given by Thomas Paine in which Franklin compares a bicameral system to “putting one horse before a cart and the other behind it, and whipping them both. If the horses are of equal strength, the wheels of the cart, like the wheels of government, will stand still;and if the horses are strong Summer2002 222 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED enough, the cart will be torn to pieces.”31 Even though Adams on several occasions accuses Franklin and Turgot as agreeing on the merits of a single house, he had no trouble in interpreting Franklin’s illustration as a vindication of two assemblies. The weight of the load itself, he affirmed, “would roll the wagon on the oxen and the cattle on one another, in one scene of destruction, if the forces were not divided and the balance formed, whereas, by checking one power by another, all descend the hill in safety and avoid the danger .” In reply to Turgot’s assertion that republics are “founded on the equalilty of all the citizens, and, therefore, ‘orders’ and ‘equilibriums’ are unnecessary,” Adams underscores the ambiguity of the concept of equality.32He asks whether citizens are supposed to be “all of the same age, sex, size, strength, stature, activity, fame, wit, temperance, constancy, and wisdom.” He denies that there could even exist “a nation whose individuals were all equal, in natural talents, and riches.” In his native state of Massachusetts as in all the others, he acknowledges, there exist inequities in wealth, birth, talents, and virtue implanted by God and by nature, which no act of legislature can eradicate. When Adams returned to America, he produced a sequel to the Defence praising the same theme of the separation of powers and based upon the same technique of seeking parallels in remote history to contemporary political problems. Originally appearing throughout 1790 as articles in the Gazette o f the United States stimulated by another French commentary, that of the Marquis de Condorcet, Un Bourgeois de New Haven, sur 1’Unite‘ de la Le‘gislature, the work was published in book form as Discourses on Davila. It consists largely of a translation with accompanying commentary on a history of French civil wars in the seventeenth century by Enrico Catarino Davila. Drawing a parallel between these internecine hostilities and the contemporary French Revolution, Adams was able t o include topics inculcating his conservative principles beyond those contained in the Defence. He begins with the doctrine that “the passion for distinction” is at the heart of man’s nature and behavior, a doctrine that he had earlier set forth in a letter to Jefferson, 9 October 1789, maintaining “that neither Philosophy, nor Religion, nor Morality, nor Wisdom, nor Interest, will ever govern nations or Parties, against their Vanity, their Pride, their Resentment or Revenge, or their Avarice or Ambition.”33In the same letter he observes that “the Loss of Paradise, by eating a forbidden apple, has been many Thousand years aLesson to Mankind; but not much regarded.” This doctrine of the desire for eminence as the ruling passion of mankind is so firmly apparent in Adams’s own personality and career that a modern Belgian scholar, Jean-Paul Goffinon, has published a book with the title Aux origines de la re‘volution amgricaine:John Adams La Passion de la distinction (1996). In his Discourses, Adams relates this psychological principle to his favorite political doctrines of the separation of powers and a bicameral legislature. He vindicates the continued use of titles, forms, and ceremonies and distinguishes between equality before the law and equality of talents. He explains the distinction for passion as a universal characteristic responsible for human gregariousness in every stage of civilization.34“A desire to be observed, considered, esteemed, praised, beloved, and admired by his fellows, is one of the earliest, as well as keenest dispositions discovered in the heart of man.” Comparable to hunger as a natural human trait, this psychogenetic drive serves as the foundation of all society. Just as it is a principal function of government to regulate this pas- Modem Age 223 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED sion, government relies upon it as a principal instrument in carrying out its other functions. Adams discards as fleeting and soon neglected such distinctions as beauty and elegance, mastery in music and the arts, and even education. The important ones are those related to birth and social recognition. Comparing the differences in the breeds of men t o those in horses, he admits that all that philosophy can say is “that there is ageneral presumption, that a man has had some advantages of education, if he is of a family of note.” Noble blood, whether hereditary or elective, like wealth, stimulates esteem, and it would be foolish to despise either one. Honors and distinctions exist in the humblest levels of society and are as eagerly pursued as in the highest. Titles, decorations, and differences in clothing serve the same purpose today as they did in Roman times. “When the love of glory enkindles in the heart, and influences the whole soul, then, and only then, may we depend on a rapid progression of the intellectual faculties.” In the light of the recognition that emulation next to self-preservation is “the great spring of human actions,” Adams affirms that the “great question will forever remain, whoshall work?”Theanswer he finds in the agency of government which will mediate between “therich and the poor, the laborious and the idle, the learned and the ignorant, distinctions as old as the creation, and as extensive as the globe.” Extending the classical concept of the great chain of being from the realm of biology to that of human relations, Adams asserts his fundamental doctrine that all men are subject by nature to equal laws of morality, and in society have a right to equal laws for their government, “yet no two men are perfectly equal in person, property, understanding, activity, and virtue.” The moral aspect of this cornerstone of conservatism manifests itself forcibly in a literary genre Adams utilized in his old age, the dialogue ofthe dead, a genre originating in classical times and revived in the eighteenth century. Directly inspired by news of Franklin’s death in 1790, Adams recorded under the title “Dialogue of the Dead, Charlemagne, Frederick, Rousseau, Otis” a scene in the afterworld in which the four political leaders engaged in c o n ~ e r s a t i o nAfter . ~ ~ inquiring whether Franklin has yet crossed the River Styx, the group agrees that during his life he had purveyed some pretty moralviews from the head, but some very immoral ones from the heart. Frederick describes his philosophy as chiefly hypothetical and conjectural and admits that he owed his own renown to amaxim that Otis had previously applied to Franklin, Populus Vultdecipidecipistus. Headds that if greatness is to be measured by its effects, Otis was one of the greatest statesmen that ever lived; the town of Boston contributed more to civilization than imperial or republican Rome; and Harvard College more than all the scholars of the Sorbonne. Charlemagne then admits that his own grandeur was likewise d u e t o t h e “detestible Maxim” imputed to Franklin. Adams uses Charlemagne’s admission to make explicit his targets in his earlier Dissertation on Canon and Feudal Law: “Leogavemethetitleof Caesar and Augustus and Magnus, and initiated that Superstition Farce of Confirmation, which cheated all Europe for so many hundred Years. I, in my turn, transferred t o the Pope, the authority which the Roman Senate and People had anciently [...I of electingandconfirmingthe Emperor. This infamous Bargain, as contemptible as the Artifices of two Lackeys, established the temporal and Spiritual Monarchies of Europe for many hundreds of Years.” Frederick then gives more encomiums t o Otis, who in turn compliments Rousseau, who modestly affirms that he did nothing but propagate the principles of Locke and Voltaire. Frederick then Summer 2002 224 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED -- praises these two for filling every volume and almost every page of their works with the themes of liberty and toleration. Otis observes that Rousseau had failed to consider the significance of emotion in world history. “The Passions of the human heart are insatiable, an Interest unballanced; a Passion uncontrolled in Society, must produce disorder and tyranny. You have nothing to do therefore to preserve equal Laws but to provide a Check for every Passion, a Reaction to silly Antics, a Contrast to everylnterest, which counteracts the Laws.” Here Adams transfers the concept of checking from the political arena to that of the moral and psychological, prefiguring later notions of the moral check proclaimed by Irving Babbitt and others. Otis also argues that there are even greater evils than those admitted by Charlemagne-that is, the denying o r doubting the moral government of the world, the existence of a future state, o r the presence of an all-perfect Intelligence. He ascribes more honor to the laws of Palestine and Jerusalem than to those of Boston and Cambridge, while affirmingas “the sublime Principle of Right order and happiness in the universe” that “Thou shalt love the Supream with all thy heart and thy Neighbour as thyself.” Adams’s fervent dedication to principle is as cogently revealed in this jeu d’esprit as in any part of his personal correspondence or published works. In both thought and behavior throughout his entire life, Adams balanced a spirit of personal enterprise with a vigilant devotion tovirtue. Somewhat of an iconoclast, however, he subjected his favorite philosophical, religious, and political systems to rigorous analysis, preserving him from intolerance on the one hand, and irrational zeal on the other. He buttressed every one of his opinions by extensive reading in both American and European letters, both ancient and modern. In politics, he combined revolutionary and modern doctrines with rigid principles of order and the containment of power. In the application of his ideals and abilities to political leadership, he was unexcelled by any American of his era. 1. Letters of Benjamin Rush, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Princeton, 1951), Vol. 2, 1127. 2. Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston, 1851), Vol. 10, 49. 3. Quoted from a letter to Benjamin Rush, cited in Page Smith, John A d a m (New York, 1962), Vol. 2, 1104. 4. The Conservative Mind (Chicago, 1963), 65,62.5. The Adams Papers: Diary and Autobiography o f John Adams, ed. L. H . Butterfield, et al. (Cambridge, Mass., 196l), Vol. 1, 23. 6. Ibid., Vol. 1, 35. 7. Ibid., Vol. 3, 305. 8. Ibid., 446. 9. Ibid., Vol. 2, 446. 10. Works (Boston, 1850), Vol. 4, 194. 11. Papers of John Adams, ed. Robert J. Taylor, et al. (Cambridge, Mass., 1977), Vol. 4, 73-74. 12. Diary, Vol. 1, 23. 13. Adams Family Correspondence, ed. L. H. Butterfield, et al. (Cambridge, Mass., 1963-1973), Vol. 1: 316-317. 14. Family Correspondence, Vol. 2, 21. 15. Diary, Vol. 3, 238. 16. Ibid., 260. 17. Papers, Vol. 1, 112. 18. Diary, Vol. 3, 331-333. 19. Papers, Vol. 4, 86. 20. Works (1851), Vol. 4, 195. 21. This work is attributed to Paine by A. Owen Aldridge, in Thomas Paine’s American Ideology (Newark, Del., 1984). 219-238. 22. Works, Vol. 4, 230. 23. The relations between Adams and Mably are described by A. O.,. Aldridge, in “John Adams Meets Mably,” in Dalhousie French Studies, Vol. 52 (ZOOO), 88-99. 24. A. 0. Aldridge, “John Adams Confronts Turgot,” in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, ed. Timothy Erwin and Ourida Mostefai (Baltimore, 2001), 75. 25. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd, et al. (Princeton, 1955), Vol. 12, 291. Russell Kirk inexplicably affirms that Adams wrote his Defense at the instigation of Jefferson and that the latter was at that time Adams’s enemy. In reality Jefferson had no influence upon the work and made no attempt to encourage Adams in the project although he did try unsuccessfully to arrange a French translation. 26. Works of John Adams, ed. C. F. Adams (1851), Vol. 4,406.27.Ibid., Vol. 4, 296. 28. Ibid. 29. Ibid., 623. 30. Ibid., 389. 31. To the Citizens of Philadelphia on the Proposal for Calling a Convention (Philadelphia, 1805). 23. 32. Works, 4, 391. 33. Papers of Thomas Jefferson,Vol. 11 (1953), 221. 34. Works, ed. C. F. Adams, Vol. 6, 232.35. Permission to discuss this document from the microfilm edition of Adams’s Papers has been granted by the Massachusetts Historical Society. : . Modern Age 225 LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED