The Looming Tower Chapter One: The Martyr (Sayyid Qutb) Sayyid

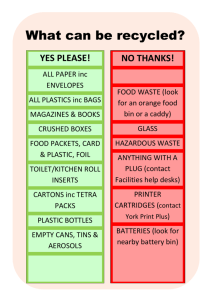

advertisement