- Figshare

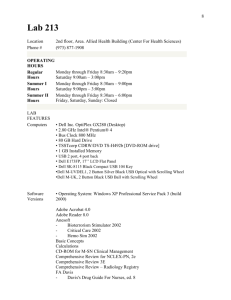

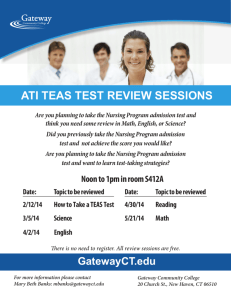

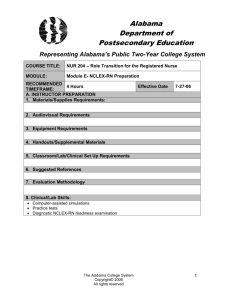

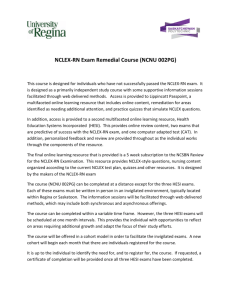

advertisement