Father(s?) of Rock & Roll: Why the Johnnie Johnson v. Chuck Berry

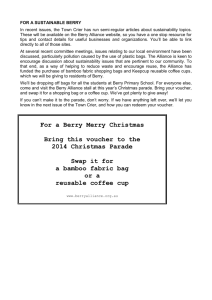

advertisement