Freeing Labor Markets by Reforming Union Laws

advertisement

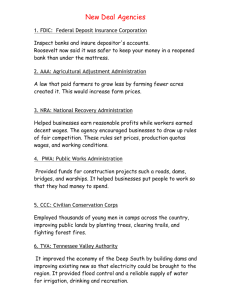

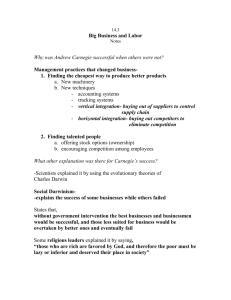

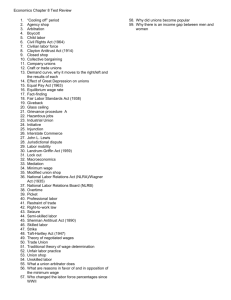

Freeing Labor Markets by Reforming Union Laws by Charles W. Baird∗ June 2011 Overview The Rise of Unions Davis-Bacon Act of 1931 Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 National Labor Relations Act of 1935 Reforming Labor Union Laws Overview In a market economy, interactions between people take place within the context of voluntary exchange. The principal role for government in a market economy is to enforce the rules of voluntary exchange by protecting individual rights. That limited-government role allows for the largest degree of personal freedom, while also spurring economic growth and promoting general prosperity. However, one area of the U.S. economy where the federal government violates the principle of voluntary exchange is in labor union law. In the 1930s, the government and the courts imposed a series of laws and decisions that damaged labor markets and did not respect the freedom of individuals and businesses to organize their own affairs and make voluntary contracts. Major federal interventions in favor of unionism—including the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 —were premised on the false idea that business management and labor are natural enemies. In fact, both management and labor are employed by consumers to produce goods and services, and so it makes no sense to assume a sharp divide between these groups. Management and labor are complementary, not rivalrous, inputs to the production process. While labor unions have declined as a share of the overall private-sector workforce, they continue to be important in some sectors. Given that U.S. workers and businesses face rising global competition, it is important for policymakers to reexamine labor union laws and repeal those laws that are harmful to economic growth and inconsistent with a free society. This essay reviews three major pieces of federal labor legislation of the 1930s, and then discusses needed reforms to update our antiquated labor rules for the modern and dynamic economy. The Rise of Labor Unions The union share of the U.S. workforce rose gradually during the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Nonetheless, even by the 1920s the union share was still less than 15 percent of the workforce.1 Federal policymakers generally stayed out of labormanagement relations, except in situations where the president felt compelled to intervene in violent strikes or strikes causing major economic disruptions, such as in the coal and railway industries.2 As the 20th century progressed, there were growing calls for federal intervention in labor relations. In 1913, Congress created a federal Department of Labor, and an official history notes that the department's founding "was the direct product of a half-century campaign by organized labor for a ‘Voice in the Cabinet.'"3 In 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act reflected the rising power of organized labor by exempting unions from anti-monopoly rules and limited the use of injunctions during strikes, which unions had pushed for. During World War I, the Woodrow Wilson administration spearheaded a large expansion in federal control over private industry, including labor relations. For example, the War Labor Board pushed for collective bargaining in the industries that it oversaw.4 These wartime interventions created precedents for later federal legislation on labor issues. During the 1920s, Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge took a laissez faire approach to the economy, and the government generally stayed out of labor issues. The Supreme Court was also restrained in its approach to labor unions. In the 1921 case, American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City Central Trades Council (257 U.S. 184), the Court held that (a) mass picketing, even in primary strikes, and even if peaceful, was inherently intimidating and so pickets must be limited to one picket per entrance; (b) pickets had to be actual employees on strike—they could not be strangers sent from union headquarters or anywhere else; and (c) the right to conduct a business is a property right, entitled to the same protection against trespass as any other property right. This Court decision was made on statutory grounds (interpreting the 1914 Clayton Act), so Congress could reverse it simply by adopting another statute or amending an existing one. Unions tried to get Congress to do so throughout the 1920s, but things didn't start to change until the election of Herbert Hoover in 1928. Hoover supported collective bargaining, and he befriended labor leaders and was accommodating to their demands.5 Hoover signed into law the Davis-Bacon Act in 1931, and followed up with the Norris-LaGuardia Act in 1932. These pro-union laws—along with the 1935 National Labor Relations Act signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—were colossal blunders. In the short-term they exacerbated the damage of the Great Depression, and in the long-term they empowered unions with monopoly privileges, while violating voluntary market relations. As a result of these laws, the share of the private-sector workforce that was unionized soared to about 35 percent by the late 1940s. Since then, structural changes in the economy have put the power of unions on the wane in the private sector, and the union share of the private sector workforce has fallen to less than 7 percent.6 But these pro-union laws of the 1930s are still in place and costing taxpayers and businesses money, while violating the civil liberties of workers in monopoly union environments. The Davis-Bacon Act of 1931 This Davis-Bacon Act, passed at the beginning of the Great Depression, requires that companies pay "prevailing wages" for work on federally funded or federally assisted construction, such as highway projects. The rules apply to contractors and subcontractors on all contracts in excess of $2,000. Prevailing wages generally means higher, union-level wages. The effect of the law is to exclude nonunion firms and nonunion workers from federal projects, which in turn increases taxpayer costs. The unions that support the Davis-Bacon Act want the government to set wages that are more favorable to their members than the marketplace would produce. The "prevailing wage" set by the Department of Labor under the Act is the inflated union wage—not a true market wage. After all, unions are insistent that they make wages higher than market-determined wages. Congress had two main purposes in passing Davis-Bacon. First, policymakers held the backwards economic idea that the government should stop prices and wages from falling during the Great Depression. Davis-Bacon was designed to keep wages artificially high. Yet falling wages and prices were precisely what were needed for labor markets to adjust to the collapse of real incomes and employment in the early 1930s. (Both prices and wages fell from 1929 to 1933, but prices fell by more than wages. Thus the real cost of hiring workers increased and pushed up unemployment). This economic fallacy about high prices and wages misled both Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt, and it did much to deepen and prolong the Great Depression. Second, Congress had a racist motivation for Davis-Bacon. Congress wanted to keep black workers from competing for jobs that had hitherto been done by white unionized labor. The racist motivation behind the legislation is plain when reading the Congressional Record of the debate in 1931. For example, Rep. Clayton Allgood, in support of the bill, complained of "cheap colored labor" that "is in competition with white labor throughout the country." These days, the law may still have racist effects if minority-owned firms are less able to pay unionlevel wages. Economist James Sherk notes "Davis-Bacon's requirements make it extremely difficult for minority, open-shop contractors to employ and train unskilled minority workers."7 By excluding more-efficient nonunion firms from federal work, Davis-Bacon pushes up the costs of all federally financed projects. A careful study by economists at the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University found that the rules increase the cost of construction projects by about 10 percent, which ultimately costs federal taxpayers about $8.6 billion annually.8 The Davis-Bacon rules should be scrapped, because they serve no interest other than protecting unionized construction workers from open competition. Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 The Norris-LaGuardia Act made five significant changes to labor law, each strengthening the power of labor unions. First, it made unionfree (yellow-dog) contracts unenforceable in federal courts. Second, it prohibited federal judges from issuing any injunctions to interrupt strikes. Third, it gave immunity to labor unions against prosecution under the antitrust laws. Fourth, it gave legal standing to strangers in labor disputes. Fifth, it insulated labor unions as organizations from any prosecution for acts committed by any individual members and officers. These changes are discussed in turn. 1. Union-Free Contracts. A "yellow-dog" contract is an agreement between an employer and a worker that, as a condition of obtaining and continuing employment, the worker will abstain from involvement with a labor union. Unions, of course, abhor such hiring contracts. They coined the term "yellow dog" to imply that any worker who entered into such an agreement was cowardly and a traitor to the working class. A more accurate label for such agreements is "union-free" contracts. The NLA made such agreements unenforceable in federal courts. (The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 made them illegal). Contrary to these current federal rules, union-free contracts should be legitimate voluntary contracts. When an employer offers a job to a worker, the offer usually consists of agreed-upon wages, benefits, time, place, and other rules for the employee. A rule that requires a worker to remain union-free would be merely part of the job description so long as there is no misrepresentation, and the worker is free to accept or reject the job offer. But this right of employers to enter into contracts with willing workers was expunged by the NLA and NLRA. Workers who wanted to escape harassment from union organizers lost one of the most important means by which they could do so. In a 1917 case, Hitchman Coal and Coke Co. v. Mitchell (245 U.S. 229), the Supreme Court noted in its decision: "The employer is as free to make non-membership in a union a condition of employment, as the workingman is free to join the union, and . . . this is a part of the constitutional rights of personal liberty and private property." Later Courts and Congresses trampled on those individual rights. 2. Strike Injunctions. The NLA prohibited federal judges from issuing injunctions to interrupt strikes—even violent strikes. Section 7(c) of the NLA says that an injunction cannot be issued unless the court has taken testimony, with witnesses subject to cross examination, and has found "that as to each item of relief granted greater injury will be inflicted upon complainant by the denial of relief than will be inflicted upon defendants by the granting of relief." In other words, the NLA forbids courts to stop aggression unless the damage to the victim is larger than the damage suffered by the aggressor as a result of the order to stop the aggression. The most basic function of government in a free society is to protect people against trespass, aggression, and violence, yet Section 7(c) is still the law of the land. 3. Labor Union Immunity. The NLA gave blanket immunity to labor unions against prosecution under the antitrust laws. Nothing done by labor unions, even if violence is involved, can be enjoined as illegal combinations in restraint of trade. That means that strike targets, their suppliers, their customers, and replacement workers may be prevented from exercising their right to voluntary trading and exchange. Antitrust laws themselves violate voluntary market exchange. Rather than promoting competition, the antitrust laws are often used in practice to protect companies that are failing in the marketplace. In a free society, neither businesses nor unions would be subject to antitrust regulation, and both would be open to challenges by entrepreneurs and new entrants. The issue with the NLA is that it gives labor unions special legal protections not afforded other private groups in society. 4. Legal Standing to Strangers in Disputes. The NLA gave legal standing to strangers in labor disputes. Thus, a company with 150 employees on strike and 700 employees that wish to continue to work can be forcibly shut down by 5,000 picketers sent from union headquarters. These NLA provisions clearly violate voluntary exchange rules regarding property rights, trespass, and contract. 5. Special Legal Protection for Unions. The NLA insulated labor unions as organizations from prosecution for any acts committed by individual members and officers. If picketers murder or maim a replacement worker who crosses a picket line, the on-strike union cannot be blamed. If the perpetrators are apprehended by local officials and convicted by local courts, no punishment may be imposed on the union. In other words, the common law doctrine of respondeat superior, or vicarious responsibility, was made inapplicable to unions. National Labor Relations Act of 1935 Federal intervention in labor markets was ratcheted up further with the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The NLRA (or Wagner Act) is still the major determinant of the structure of private-sector unionism in the United States. The ostensible purpose of the NLRA was to promote equality of bargaining power between employers and employees. Unionists present the history of unionism as a long and bitter struggle of employees as underdogs against employers as their exploitative masters. The real struggle, however, has been between some workers who want to create a union monopoly, or cartel, and other workers who wish to remain independent. The unionist view of history triumphed during the New Deal. The Wagner Act was explicitly pro-union, anti –independent worker, and anti-employer. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 restored some balance to labor relations, but federal labor law is still strongly biased in favor of unions and against independent workers and employers. The NLRA violated voluntary exchange in the free economy in four major ways. It imposed exclusive union representation on companies and workers, it introduced rules for union security or forced union dues, it imposed coercive ("good faith") bargaining rules, and it banned company unions. These four provisions of NLRA are discussed in turn. 1. Exclusive Representation The NLRA imposes "exclusive representation" on employees and employers in section 9(a). That means monopoly unionism. If, in a certification election, a majority of workers in a bargaining unit vote to be represented by Union A, then all the workers who were eligible to vote must submit to those representation services. Union A, by force of law, represents the workers who voted for it; but it also represents the workers who voted for another union, the workers who voted to remain union-free, and the workers who did not vote. It is a winner-takeall election rule. Individuals are prohibited even from representing themselves on the terms and conditions of their employment and other matters that come under "the scope of collective bargaining." Employers may not deal directly with individual workers. Individual workers have no voice. Only a certified union may speak. Unionists justify exclusive representation by analogy to political elections, whereby the winning candidate is the exclusive representative of all voters in a district. Those who voted against the winning candidate and those who didn't vote must accept the candidate as their exclusive representative in the legislature. By analogy, unionists argue, it is proper to force all workers to accept the representation services of a union selected by majority vote, as "workplace democracy." To the contrary: unions are not governments. The Framers of the Constitution drew a bright line separating rules for decisionmaking in government and rules for decisionmaking in the private sphere of human action. Governments are natural monopolists regarding the legal use of force in their respective jurisdictions. Like all monopolists, they are prone to abuse their power. Democracy is a means by which the governed have some control over those who wield governmental power. According to the Framers, it is legitimate to override individual preferences in favor of majority rule only with respect to the enumerated, limited powers of the federal government. Everything else should be left to individuals to decide—irrespective of what a majority of others may prefer. An individual is not forced to submit to the will of a majority in the choice of religion, nor should he be in the choice of a representative in the sale of his labor services. Exclusive representation is a violation of voluntary exchange. It implies that an individual does not own his labor. Rather, a majority of his colleagues own it. It is a violation of a dissenting worker's freedom of association. Freedom of association in private affairs requires that each individual is free to choose whether or not to associate with other individuals, or groups of individuals, who seek to associate with him. Freedom of association forbids any kind of forced association, even by majority vote. The sale of one's labor services to a willing buyer is a quintessentially private act. Current rules that force a minority of workers to subject themselves to the will of a majority of their colleagues in the sale of their labor services is bad enough. Worse yet would be for government to allow unions to gain the exclusive representation privilege simply by collecting a majority of workers' signatures. That is the idea behind the deceptively named Employee Free Choice Act, which is pro-union legislation pending in Congress and supported by President Obama. Currently, signatures collected on authorization cards are used as the basis to call secret-ballot elections. Workers can avoid union intimidation by signing cards and then voting against the union on the secret ballot. But under the Employee Free Choice Act, secret-ballot elections would be replaced with card-check certification of unions as the monopoly bargaining agents for workers. Under card-check rules, a union would become the monopoly representative of all non-managerial workers in an enterprise if more than half of those workers signed a card indicating their support for such representation. Signatures would be collected by union organizers in face-to-face confrontations with workers, and these organizers would likely remind any dissenters that the union knows where they and their families live. The potential for coercion of workers is obvious. Luckily, the election of a majority Republican House in 2010 has likely killed this legislation for the time being. 2. Union Security To help unions enforce their monopolies, the NLRA imposed "union security" rules on the workplace. Union security is the idea that workers who are represented by unions with monopoly bargaining privileges should be forced to join, or at least pay dues to, the union. The NLRA permitted four forms of union security: the closed shop, the union shop, the agency shop, and maintenance of membership. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act eliminated the closed shop, but it still permits the latter three. In a closed shop a prospective employee must already be a union member to be hired. In a union shop, an employee does not have to be a member when hired, but in order to continue employment he must become a union member after a probationary period on the job (usually 30 days). In an agency shop, employees are not required to join the union, but must pay union dues and fees in order to keep their jobs. Under maintenance of membership, no one is forced to join or pay dues, but if a worker voluntarily joins the union that employee may not resign membership as long as an existing collective-bargaining contract between the union and the employer is in effect. Section 8a(3) of the NLRA states that it is an unfair labor practice for an employer, "by discrimination in regard to hire or tenure of employment or any term or condition of employment to encourage or discourage membership in any labor organization [except the employer may] require as a condition of employment membership therein on or after the thirtieth day following the beginning of such employment." In other words, employers may not encourage or discourage membership, they may only agree with a union to require it. Unions justify this coercion on the grounds that under exclusive representation they represent all workers in their bargaining units whether individual workers want such representation or not. Thus, unions say that every worker should be forced to pay for representation; else, some would be "free riders." However, this alleged free-rider problem could be eliminated simply by repealing exclusive representation. If unions bargained only for their voluntary members and no one else, there would be no free riders. After the overreach of labor laws of the 1930s, and a spike in strike activity in 1946, Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act of 1947 over the veto of President Truman. The Act allowed state governments to pass right-to-work laws banning union security provisions. Right-to-work laws are currently in place in 22 states.9 In the 1988 decision in Communications Workers of America v. Beck (487 U.S. 735), the Supreme Court declared that the dues of union members could not be used for purposes not directly related to collective bargaining, particularly for political purposes. In other words, employees forced to pay union dues under the NLRA do not have to contribute to a union's partisan political activities. Unfortunately, the federal government has done little to protect this right of workers. 3. Forced Bargaining Rules The NLRA imposed a duty to bargain on both employers and unions in sections 8(a)5 and 8(b)3. Section 8(d) adds that the duty is a requirement to bargain "in good faith." Case law has established that, in practice, "good-faith bargaining" means that each side must compromise with the other. Such mandatory bargaining obviously violates voluntary exchange. Consider that under ordinary contract law, if any party to the contract is forced to bargain, the contract is null and void. By contrast, no contract reached under the forced-bargaining rules of the NLRA can be a voluntary exchange contract. 4. Company Unions A company union is one formed and administered by an employer, generally designed to improve labor-management relations. In the 1920s, numerous company unions were set up as a means of giving voice to workers in workplace decisionmaking. At the time, these organizations were considered very progressive, and employers such as Goodyear Tire who used this form of labor relations were considered enlightened. In 1922, the Leeds and Northrup Cooperative Association, a company union, instituted the nation's first unemployment insurance plan. The National Industrial Recovery Act was enacted in 1933. Section 7(a) of NIRA said that employers had to: (a) allow their employees to join unions "of their own choosing," and (b) bargain with those unions. To meet this requirement, many employers formed company unions and bargained with them. Independent unions, such as the American Federation of Labor, didn't like this competition, which might have reduced their power and membership. As a consequence, the NLRA of 1935 outlawed company unions. Section 8(a)2 of the NLRA forbids employers to form or support any labor organizations that deal with management on the terms and conditions of employment. These days, under the pressure of global competition, many American companies and employees want to form labor-management cooperation committees to give workers more voice in decisionmaking. These committees are sometimes called "quality circles" or "employee involvement teams."10 Yet in the 1992 Electromation case, the National Labor Relations Board declared these cooperation committees to be illegal company unions.11 Because of that decision, the law today is that labor-management cooperation that is not unionmanagement cooperation is illegal. Reforming Labor Union Laws The ideas embodied in the federal union laws of the 1930s make no sense in today's dynamic economy. Luckily, constant change and innovation in the private sector has relegated compulsory unionism to a fairly small area of U.S. industry. But the damage done by federal union legislation is still substantial. Many businesses and industries have likely failed or gone offshore because of the higher costs and inefficiencies created by federal union laws, while other businesses may not have expanded or opened in the first place. So the damage of today's union laws is substantial, but often unseen, in terms of the domestic jobs and investment that the laws have discouraged. Davis-Bacon, the NLA, and the NLRA serve the particular interests of unionized labor rather than the general interests of all labor. These laws abrogate one of the most important privileges and immunities of American citizens—the rights of individual workers to enter into hiring contracts with willing employers on terms that are mutually acceptable. Unfortunately, no Supreme Court has fundamentally challenged these laws since the 1930s. It is time for Congress to do so, and here are seven important reforms for it to pursue: 1. Eliminate Exclusive Representation. The principle of exclusive representation, as provided for in the NLRA, should be repealed. Workers should be free on an individual basis to hire a union to represent them or not represent them. They should not be forced to do so by majority vote. Unions are private associations, not governments. For government to tell workers that they must allow a union to represent them is for government to violate workers' freedom of association. Restrictions on the freedom of workers to choose who represents them should be eliminated. 2. Pass a National Right-to-Work Law. Short of eliminating exclusive representation, Congress should at least pass a national right-towork law. Under this second-best reform option, workers would still be forced to let certified unions represent them, but no worker would be forced to join, or pay dues to, a labor union. In the 1988 Beck decision, the Supreme Court declared that the dues of union members could not be used for political purposes. Congress should protect this right of private-sector workers by enacting a statute incorporating the provisions granted to government workers in the 1986 Court decision in Chicago Teachers Union v. Hudson (475 U.S. 292). The importance of codifying Beck is illustrated by the NLRB's 1996 decision in California Saw and Knife Works. In that case, the NLRB greatly circumscribed workers' Beck rights, even finding that unions could use their own staff accountants to determine how much of their expenditures were for non-collective-bargaining purposes. 3. Repeal Davis-Bacon Rules. By excluding more-efficient nonunion firms from federal work, Davis-Bacon pushes up the costs of all federally financed projects. The Davis-Bacon rules should be scrapped, because they serve no interest other than protecting unionized construction workers from open competition. Taxpayers would realize savings of about $9 billion annually as federal contracting efficiency was improved. 4. Allow Company Unions . Congress should repeal section 8(a)2 of the NLRA, which bans so-called company unions. Labormanagement cooperation is important for the ability of American businesses and workers to compete in the global marketplace. Workers who want to have a voice in company decisionmaking without going through a union should be free to do so. The current ban on cooperation, as strengthened by court decisions, makes no economic sense. Greater workplace cooperation would increase workplace productivity, and productivity is the ultimate determinant of U.S. wages. So repealing section 8(a)2 of the NLRA would be a win for businesses and workers alike. 5. Protect Replacement Workers. Congress should codify the Supreme Court's 1938 ruling in NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph (304 U.S. 333) that employers have an undisputed right to hire permanent replacement workers for striking workers in economic strikes. 6. Allow Nonhiring of Union Organizers. Congress should repeal section 8(a)3 of the NLRA, which makes it an unfair labor practice for an employer to discriminate against a worker on the basis of union membership. In 1995, the Supreme Court ruled in NLRB v. Town & Country Electric (516 U.S. 85) that employers can be forced to hire paid union organizers as ordinary employees. Unions send paid organizers ("salts") to apply for jobs at union-free firms and, if employed, to promote pro-union sympathies. The Court said that employers could not resist by firing or refusing to hire salts. In other words, employers must hire people whose main intent is to subvert their business, which is like telling a homeowner that it is illegal to exclude visitors who want to burglarize their home. That makes no sense, and Congress should repeal this section of the NLRA. 7. Create Greater Union Financial Transparency. The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 required unions to publicly disclose basic financial information so that their members can see how their dues are being spent. However, the Act was never very effective, as unions stashed different piles of money into a variety of trust funds that were not disclosed. In the George W. Bush administration, Labor Secretary Elaine Chao tried to fix these problems by creating new forms and reporting requirements to provide greater union financial transparency.12 Unfortunately, it appears that the Obama administration is shelving some of these reforms, so Congress should step in and make sure that the Chao reforms are fully implemented. ∗ Charles W. Baird is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, California State University, East Bay. 1 Claude Fischer, "Labor's Laboring Effort," Berkeley Blog, http://blogs.berkeley.edu/2010/09/09/labor%E2%80%99s-laboring-effort. 2 R. Boeckel, "Strike Emergencies and the President," CQ Researcher, August 1, 1925. 3 Judson MacLaury, "History of the Department of Labor, 1913–1988," Department of Labor, 1988, chap. 1, www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/hs75menu.htm. 4 C. E. Noyes, "Labor in Wartime," CQ Researcher, July 20, 1940. 5 H. M. Cassidy, "Organized Labor in National Politics," 6 Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Union Members 2010," CQ Researcher, August 31, 1928. news release, January 21, 2011. 7 James Sherk, "Davis-Bacon Extensions: The Heritage Foundation 2010 Labor Boot Camp," Heritage Foundation, January 14, 2010. 8 Sarah Glassman et al., "The Federal Davis-Bacon Act: The Prevailing Mismeasure of Wages," Beacon Hill Institute, Suffolk University, February 2008. 9 See "Right to Work States," National Right to Work, www.nrtw.org/rtws.htm. 10 For further discussion, see James Sherk, "Declining Unionization Calls for Re-Envisioning Workplace Relations," Heritage Foundation, January 21, 2011. 11 Charles W. Baird, "Are Quality Circles Illegal," Cato Institute Briefing Paper no. 18, February 10, 1993. 12 James Sherk, "Congress Should Block Union Transparency Rollback," Heritage Foundation, December 16, 2010. Cato Institute 1000 Massachusetts Avenue N.W. Washington D.C. 20001-5403 Telephone (202) 842-0200 Fax (202) 842-3490 Source URL: http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/labor/reforming-labor-union-laws