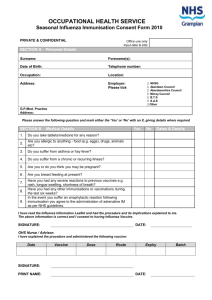

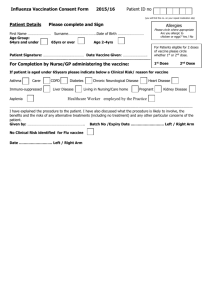

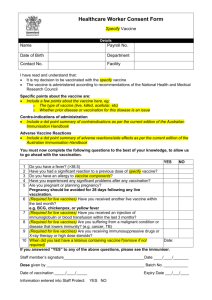

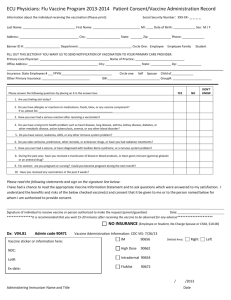

UK guidance on best practice in vaccine

advertisement