LECTURES ON COMPARATIVE LAW OF CONTRACTS

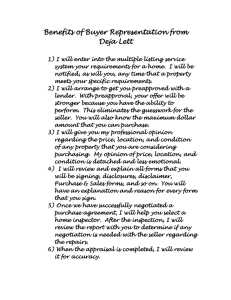

advertisement