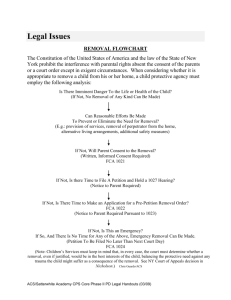

Removal as a Political Question - University of Chicago Law School

advertisement