Restoring the Peace: The Edict of Milan and the

advertisement

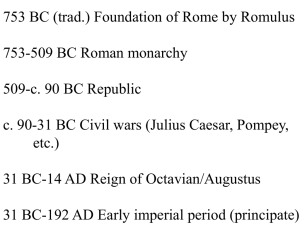

Restoring the Peace: The Edict of Milan and the Pax Deorum Jason A. Whitlark Baylor University, Waco TX 76798 After his victory over Maxentius, Constantine met Licinius in Milan where he gave his half-sister in marriage to Licinius. At that time, Constantine and Licinius drafted letters to be circulated among the governors of the Eastern Empire. One of those correspondences is the so-called Edict of Milan. From the perspective of Christians, such as Eusebius, this declaration constituted the triumph of Christianity over paganism.1 But within the larger imperial discourse the Edict betrays something else. John Curran, in his analysis of the legal texts of Constantine's reign, makes an interesting passing comment about the so-called Edict of Milan. After quoting a key section from this letter, Curran writes, "The pax deorum was best served by the inclusion of Constantine's new god alongside those of the state."2 This article will attempt to demonstrate how the socalled Edict of Milan participates in the imperial rhetoric of the pax deorum. To this end we will examine the imperial discourse about the pax deorum. Then we will examine the Constantine-Licinius correspondence in light of this discourse. Finally, we will consider what this evidence suggests about the "conversion" of Constantine in 312 CE. The Imperial Discourse of the Pax Deorum W. Warde Fowler describes the pax deorum as a quasi-legal covenant that ensued when humanity and the gods were rightly related.3 This restored covenantal relationship was regarded as key element to the success of Rome's worldwide dominion. The discourse of the pax deorum was entrenched in the imperial propaganda of the Augustan principate and persisted even in Constantine's accession to imperial rule. In this section we will examine some key pieces of evidence from the Augustan period that articulated the key features of the pax deorum. Then we will take a look at how Eusebius continued to articulate this aspect of the imperial discourse in his bios and panegyric of Constantine. The Pax Deorum Typified in the Ara Pacis Let us first look at the articulation of the pax deorum during the Augustan principate. In 9 B.C.E. the Senate voted to honor Augustus's military victories in Spain and Gaul with an altar to be erected in the Field of Mars upon his return l Cf. Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 10.1-4; Laud. Const 6.1-18. John Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome: The Legal Evidence," Gfl-43(1996):69. 3 W. Warde Fowler, The Religious Experience of the Roman People from the Earliest Times to the Age of Augustus (London: MacMillan and Co., 1911), 169, 431. 2 PERSPECTIVES IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES 310 to Rome. The altar was to be called Ara Pads Augustae. The altar typified two key elements of the pax deorum: peace achieved through victory over Rome's enemies and peace mediated by the pious emperor. Thus, as one approached the altar from the rear, one would see two images. One of the images depicted the goddess Roma seated and at rest. She is seated atop of shields heaped in a pile indicating victory after war. The other image illustrated the goddess Pax sitting amidst symbols of abundance. The two winds are portrayed on each side of her, one seated upon a goose and the other upon a sea monster. Both creatures are docilely under the beneficent control of each wind. These two images of Pax and Roma together symbolized the abundant gifts Pax had bestowed upon the Empire through Roman victory over its enemies.5 Furthermore, by putting all this imagery on an altar, the Romans typified that their victory was predicated upon a restored relationship with the gods. In fact, military defeat was a sure sign to the Roman mind that the pax deorum had been disrupted and that the populace now lived under the ira deorum. In Livy's Ab urbe condita there are two primary illustrations. First, Book 5 of Livy's Ab urbe condita narrates the destruction of Veii, the sack of Rome by the Gauls, and Rome's deliverance followed by Camillus' speech to the Romans. The defeat of the Romans by the Gauls, according to Livy, was chiefly due to Roman impietas that dissolved the pax deorum. Gabriella Gustafsson has shown that the central theological thread that holds these elements of the narrative together is that victory is due to the pietas of the Roman people. Roman pietas maintained the pax deorum. Gustafsson lists five ways this connection is indicated in the narrative: the performance of correct rituals (19.1, 21.1); showing the gods due respect (22.4); making up for bad omens (19.1); making various vows to the gods (19.6, 21.2-3); and keeping vows to the gods (22.6-7). Further, the favor of the gods could only be acquired by pietas.6 In the concluding speech of Camillus to his fellow Romans, Camillus declares, "things turned out well for us when we obeyed the gods" (51.5 [Foster, LCL]).7 The second illustration comes from Livy's narration of the Second Punic War. During the war with Carthage, the Romans lived in fear of the Carthaginian general, 4 For a succinct discussion of these points see, J. Rufus Fears, "The Cult of Jupiter and Roman Imperial Ideology," ANRW 17.1:36-38. For a fuller discussion see his "Theology of Victory at Rome: Approaches and Problems," ANRW 17.2:736-826. Cf. Klaus Wengst, Pax Romana and the Peace of Jesus Christ (trans. John Bowden; London: SMC, 1987), 1119. 5 For further discussion of these images see, Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age ofAugustus (trans. Alan Shapiro; Jerome Lectures 16; Ann Arbor: Michigan, 1988), 172-79. See also Nancy Thomson de Grummond, "Pax Augusta and the Horae on the Ara Pacis Augustae," AJA 94 (1990): 663-77. Printed on coins was PAX AVGVSTA, indicating that Pax performed her function through Augustus's activity. See J. Rufus Fears, "The Cult of Virtues and Roman Imperial Ideology," ANRW 17.2:885, 889 n. 353, 936 n. 553. By 9 B.C.E., some 20 years after Actium and the two power settlements with Senate in 27 and 23 B.C.E., this altar is representative of the mature propaganda of the Augustan Principate. 6 Gabriella Gustafsson, Evocatio Deorum: Historical & Mythical Interpretation of Ritualized Conquests in the Expansion ofAncient Rome (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Historia Religionum 16; Uppsala: Uppsala University Press, 2000), 95-97. 7 Gustafsson, Evocatio, 97-98. JOURNAL OF THE NABPR 311 Hannibal, because Roman legions were unable to wage a successful campaign against his forces in Italy. Livy writes that, when Quintus Fabius Maximus took the office of dictator to deal with the Carthaginian threat, he first took up the matter of religion in order to discover how the Romans might appease the wrath of the gods (irae deum; 22.9.7) that was frustrating Roman victory over the Carthaginian forces. In these two examples and throughout his history, Livy is supremely concerned with how the Romans placated the deities in order to secure victory and peace.8 The second element of the pax deorum indicated by the images on the Ara Pads is that pax was mediated by the pious emperor. Pietas was the means to the pax deorum. Thus, the reliefs down the side of the altar depict the people in procession to the altar. Leading the people is a pious Augustus, hooded and wearing the toga, and the royal family with the purpose of fulfilling their duty to the gods and thereby ensuring the ongoing peace.9 The scene is completed on the next side of the altar with pious Aeneas preparing to make a sacrifice to the gods. "The relief of the pious Aeneas sacrificing invoked the historical archetype of the pietas ergos deos upon which the peace of the restored order now rested."10 Thus the imagery upon the Ara Pads represented to all the inhabitants of and travelers to Rome that the pax deorum was maintained by piety. Further, the emperor led the senatorial members and the populace in preserving the pax deorum through pie tas. Again, in Livy's Ab urbe condita Camillus is the pious leader who directs the victory over Veii and the deliverance of Rome from the Gauls. Camillus is the type of pious leader who can lead the Romans back to victory.11 Roman piety in the imperial age was chiefly directed to supplicating the gods for the health and well-being of the emperor as Pliny indicates in his panegyric to Trajan.12 Thus the Roman people and the Roman emperor forged a synergistic relationship that ensured the pax deorum. The Pax Deorum Narrated in the Aeneid These aspects of the pax deorum can also be found in the foundational narrative of Roman imperial power, Virgil's Aeneid. In the story of the Aeneid^ the 8 Cf. Ab urbe condita 4.30.9-11; 7.2.2-4; 21.62.4; 22.1.16; 22.9.7-11; 22.57.2; 24.10.1-11.1; 24.44. 9 Many of the statues of the emperor throughout the empire depicted him wearing the toga with a veiled head thus chiefly representing him as the pious Roman (Zanker, "The Power of Images" in Paul and Empire, 74). Constant exposure to such images impressed upon the imperial inhabitants that piety, primarily that of the emperor, maintained the divine peace and prosperity and justified Roman rule. ,0 Fears, "The Cult of Virtues," 886. 1l Cf. Gustafsson, Evocatio, 97-98. There appears to be some connection between Camillus and Augustus. Camillus is implicitly connected to Aeneas and explicitly connected to Romulus as the second founder of Rome (96). We find these connections in the Augustan Principate in both the Aeneid and his forum. Gustafsson notes that three models of interpretation have been applied to this observation: (1) Camillus is put forth as the ideal model for the Roman leader, such as Augustus; (2) Augustus is the realized actuality of Camillus; and (3) Camillus is the critically contrasting image to the actuality of the Augustan Principate (12627). n Cf. Pan. 67.3, 94.2. 312 PERSPECTIVES IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES preeminently pious Trojan, Aeneas, fulfills his destiny to establish the foundations of the Roman Empire. Virgil in the Aeneid declares that Rome's mission was "to bring the whole world under law's dominion" (4.229-30).l3 In fact the mission of Rome is stated explicitly in Aeneid Book 6: "Roman, be sure to rule the world (by these your arts), to crown peace with justice, to spare the vanquished and crush the proud" (851-53 [Fairclough, LCL]). Additionally, none other than Jupiter has bequeathed worldwide dominion to Rome. Jupiter declares that "for these [Romans] I set neither bounds nor periods of empire, dominion without end I have bestowed" (1.279-80 [Fairclough, LCL]). Aeneas's journey, however, from Troy to Rome, and thus the completion of his fated objective, is continually being frustrated by his primary divine antagonist, Juno. She engages in subterfuge all along Aeneas's journey to lay the foundations of what would become the Roman Empire. Not until peace is made with Juno establishing a pax among all the gods can Aeneas make a beginning for the Roman Empire. In the end, Juno is pacified when Jupiter tells her: "From them shall arise a race, blended with Ausonian blood, which you will see overpass men, overpass gods in pietate, and no nation will celebrate your worship with equal zeal" (12.838-40 [Fairclough, LCL]). After hearing Jupiter's declaration, Virgil writes that "Juno assented to this and joyfully changed her purpose" (12.841). Livy records that after the defeat of Veii, the Romans conveyed Juno from her sanctuary there to Rome and removed the objects of the gods "more in the manner of worshippers than plunderers" (Ab urbe condita 5.22.4-5 [Foster, LCL]). In fact Livy writes that one of the Romans asked Juno if she were willing to go to Rome and the statue of Juno responded by nodding her assent. Livy also recounts a speech by Quintus Marcus Philippus who states why Rome ruled the earth: "For the gods support the cause of duty (pietati) and faithfulness (//deique), the qualities by which the Roman people has climbed to so great an eminence" (44.1.11 [Schiestinger, LCL]). What we see in the Aeneid confirms what we saw earlier. Roman dominion was established by and an indication of the pax deorum. Moreover, that peace was founded preeminently upon the piety of the Roman ruler (i.e., Aeneas) and more generally upon the piety of the Roman populace. What is more, pax needed to be established with all the traditional deities for there to be a real pax deorum. Though Jupiter and the other gods do not stand opposed to Aeneas and his divinely-appointed mission, Aeneas does not experience victorious peace and dominion as long as Juno remains unreconciled. The Pax Deorum Exploited by Eusebius These key features of the pax deorum that were foundational to imperial ideology persisted in imperial Rome even with the rise of Constantine to the imperial throne in the early fourth century. For instance, Constantine is the God-chosen ,3 I am following Robert Fitzgerald's translation, Virgil, The Aeneid (Vintage Classics; New York: Random House, 1990), 103.1 am here taking the more "positive" reading of the Aeneid over the "pessimistic" reading of the Harvard School. For a survey of twentiethcentury scholarship on the Aeneid, see S. J. Harrsion, "Some Views of the Aeneid in the Twentieth Century," in Oxford's Readings in Vergil's Aeneid (ed. S. J. Harrsion; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), 1-20. JOURNAL OF THE NABPR 313 emperor who restores peace and order to the world. Eusebius even draws upon the Gigantomachy when he declares that Constantine is "the victor over the whole race of tyrants and destroyer of the God-battling giants" (Vit. Const. 1.5.1).15 Eusebius recounts that God put "all barbarian nations beneath [Constantine's] feet" (Vit Const. 1.46). Thus, by his defeat of tyrants and barbarians, Constantine establishes a new age of peace through victory, "a rebirth to a fresh new life" (Vit. Const. 1.41.2). Again, Empire-wide peace is established through victory and victory is an indication of a restored, at least for Eusebius, pax Dei.16 More importantly, this restored peace with the Christian God was pre­ served by pietas or ευσέβεια. As with the emperors that preceded Constantine, Constantine is supremely pious. The imperial coinage depicts a pious Constan­ tine praying.17 Constantine is the teacher of ευσέβεια (Vit. Const. 1.5.2). As Eusebius declares him, he is ό ευσεβή Βασιλέα (Hist, eccl 10.9.7), and God is "the champion of the pious (των ευσεβών)" (Hist. eccl. 10.2.1 [Oulton, LCL]). Thus, God-given victory was also the indication of piety while defeat was a sign of impiety. Constantine himself in his letter to the provincials of Palestine dec­ lares that ασεβή towards the supreme God of the Christians results in defeat and disaster.18 Just as the pious Augustus restored and built the temples of the gods, the pious Constantine restored and built places of worship for Christians. 9 He built a basilica venerating the site of Jesus' resurrection,20 His mother also vene­ rated other sacred sites of Jesus' life with shrines.21 Further, he destroyed places of pagan worship.22 He also suppressed heresy among the Christians. 14 Cf. Vit. Const. 2.28.2. All quotes follow the translation from Life of Constantine: Introduction, Transla­ tion, and Commentary by Averli Cameron and Stuart G. Hall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999). The Greek text consulted was F. Winkelmann, Eusebius Werke, Band 1.1: Über das Leben des Kaisers Konstantin (Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller, Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1975), 3-151. 16 Cf. J. Rufus Fears ("Theology of Victory at Rome: Approaches and Problems," ANRW 17.2:752) who argues that, for Eusebius, Constantine's victory was the Christian god's victory over imperial paganism. 17 Cf. Vit. Const. 4.14.2. Carlos F. Noreña ("The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues," The Journal for Roman Studies 91 [2001]: 135) has demonstrated that one of the most advertised virtues on the imperial coinage was pietas. ,8 Cf. Vit. Const. 4.24.2-3. 19 Cf. Vit. Const. 1.42; 2.42.2-46.4; 3.47.4-53.4. 20 Cf. Vit. Const. 3.29.1-2. 21 Cf. Vit. Const. 3.43.1-3. 22 Cf. Vit. Const. 2.45,1; 3.54-58; 4.23-25. Earlier imperial policy had been to stamp out some indigenous religions in the frontiers of the Empire and non-traditional religions within the Empire that seemed to be at odds with Rome's imperial mission. See Peter Garnsey and Richard Sailer, The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture (Berkley: University of California Press, 1987), 169, 172-73. 23 Cf. Vit. Const. 3.64-65. 15 314 PERSPECTIVES IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES According to Eusebius, Constantine attended to all things that pertained to the peace with God (τα της ειρήνης του θεού, Vit. Const. 1.44.2).24 Not only was Constantine's piety of paramount importance but the pie­ ty of the Roman populace was vital to this new pax Dei. Just as previous emperors had called upon their subjects to sacrifice to the gods on their behalf for the prosperity of the Empire, so also Constantine petitioned the Christians to pray to God on his behalf for the sake of the welfare of the Empire.25 All of these points reflect the imperial propaganda of the pax deorum filtered through Eusebius's own Christian articulation of the imperial discourse. Eusebius is not only attempting to indicate the superiority of the Christians' god, but he is doing it in such a way that vindicates Constantine as the true God-chosen emperor to an imperial audience. Now in light of this discussion let us look at the so-called Edict of Milan. The Edict of Milan and the Pax Deorum Prior to the rise of Constantine to power, Christians experienced one of their darkest periods of persecution under Diocletian. His persecution had not only targeted the Christians but any religious expression that denied the traditional imperial religion and deities. In one document he states: "A new cult ought not to find fault with traditional practices. For it is a most serious offense to re­ examine matters decided and fixed once and for all by our ancestors" (Coli. Mos. Et Rom. Leg. 15.3.2-3).26 From the imperial perspective, the exclusivist Christian claims upset the pax deorum.21 Christians were blamed for hindering the success of sacrifices and so, in 303 CE., the Edict of Nicomedia was issued in order to suppress Christianity.28 We find a similar complaint by imperial pa­ gans recorded by Tertullian at the beginning of the third century. He writes that whenever there were outbreaks of plague or natural disasters Christians were blamed because they angered the gods by forsaking their worship (cf. Αρ. 40). Roldanus states that historians often depict the failure of traditional Roman religion to secure imperial peace from Decius onwards. Additionally, Plague and depopulation, abandonment of agricultural lands by peasants fleeing as taxes weighed ever heavier on the reducing tax base, the de­ cline of slavery, coinage debasement, inflation, demonetization, of the 24 Rudolph Storch ("The 'Eusebian Constantine/ " CH 40 [1971]: 145-46) lists four aspects of the image of Constantine that Eusebius portrays in Vita Constantini: (1) all success and benefit derive from the favor of divinity; (2) only the pious receive divine favor; (3) di­ vine favor for a pious ruler is primarily indicated by military victory; and (4) with victory secured, divine favor goes on to produce peace and unity in the Empire. These four aspects were not invented by Eusebius but were employed from traditional imperial ideology, exis­ tent from foundations of the Empire (cf. Storch, "The 'Eusebian Constantine,' " 153-55). 25 Cf. Vit. Const. 4.14.2. 26 Quoted in A. D. Lee, "Traditional Religions," in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine (ed. Noel Lenski; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 166. 27 Cf. Johannes Roldanus, The Church in the Age of Constantine: The Theological Challenges (New York: Routledge, 2006), 51-52. 28 In 299 c.E. Diocletian had purged the army of Christians. JOURNAL OF THE NABPR 315 economy, the demoralization of the educated urban elites who had main­ tained classical culture, the expansion of new religions: all these and more were woven into a "theory of everything" to explain both crisis and 29 transformation. What I propose is that, within the Roman imperial context, Constantine's march to victory under the patronage of the Christian's god was not a result of the per­ ception of the failure of the traditional religion (though Eusebius depicts it in this manner).30 If we examine the Edict of Milan in light of the imperial dis­ course of the pax deorum, then one perspective that the document betrays is that Constantine was upholding the traditional imperial religion but restoring peace with all the gods, even the Christian god who had been mistakenly excluded for all this time. Let us now examine the so-called Edict of Milan to this end. The so-called Edict of Milan has been preserved in two sources: a Greek translation in Eusebius's Historia ecclesiastica and a Latin transcription in Lactantius's De Mortibus Persecutorum.31 The Edict lifts the ban on Chris­ tianity but also other previously banned religious devotion to other deities. The Edict grants "both to the Christian and to all the free choice of following what­ ever form of worship they pleased" (Hist. eccl. 10.5.4 [Oulton, LCL]). Thus the Edict is not a declaration for monotheism or the forsaking of traditional imperial religions. The Edict expands the canopy of what counts for officially sanctioned religious expression in the Empire. The purpose of resending the former policies and adopting these new ones was so that "all the divine and heavenly powers that be might be favoura­ ble to us and all those living under our authority" (Hist. eccl. 10.5.4 [Oulton, LCL]). Again, the Edict is issued so that "the Divinity may in all things afford us wonted care and generosity" (Hist. eccl. 10.5.5 [Oulton, LCL]). The Edict ends expressing the hope that "by this method, as we have also said before, the divine care for us, which we have already experienced in many matters will re­ main steadfast continually" (Hist, eccl 10.5.13). In these statements we have what amounts to the imperial discourse of the pax deorum. Constantine and Li­ cinius hoped that in issuing this order that all the divine powers worshipped under the Roman aegis would be placated and made favorable to Roman Impe­ rium. Most of the Edict is concerned with the Christians, the cessation of hostilities against them, and the restoration of confiscated property. Again, the hope is that by implementing these directives the Empire, which was once anta­ gonistic against the Christian god, will now recognize his legitimacy and thus bring about peace with Constantine's patron deity. Roldanus, The Church in the Age of Constantine, 37. Roldanus sees the essential crisis being between the emperor and the management of the army. 30 Cf. Vit. Const. 1.27.1-3. Here, Eusebius recounts how Constantine considered the benefits the Christian god brought to his father and the misfortunes of those devoted to pa­ ganism. 3 'interestingly, Erika Cartunuto ( "Six Constantinian Documents [Eus. Η.E. 10, 57]," VC 56 [2002]:73) has argued that the Constantinian documents that make up Book 10 in Eusebius's Historia ecclesiastica were grouped together in an anti-Donatist context in order to indicate who were the legitimate recipients of the imperial policy of restitution and exemp­ tion. PERSPECTIVES IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES 316 While the Edict is clearly pro-Christian it is not exclusively Christian. Moreover, since the Edict is not a declaration of monotheism nor a denial of traditional imperial religion, what we are dealing with is an articulation of the pax deorum. Here the resolution of the Aeneid provides us a model. In Book 12, the pax deorum is achieved when once the last god antagonistic to Aeneas's fate, i.e., the founding of Rome, is reconciled to Aeneas and his mission. Once Juno's hostilities have ceased, Aeneas, his companions, and the peoples of Italy can begin to lay the foundations of Rome and its march to world rule. Prior to the Edict of Milan, Rome had viewed the Christians and their worship of God as a cause of the ira deorum. Their forsaking of the traditional deities contributed to the declining Empire by disrupting the pax deorum upon which Roman Imperium depended. The Edict of Milan turns this reasoning on its head. Instead of Christian (and others) being part of the problem, they become part of the solution. The Edict calls for the Empire to be reconciled to this god of the Christians. The Christian god (and others) is to be placated and recognized within the confines of officially sanctioned traditional imperial religion. "The pax deorum was thus best served by the inclusion of the Constantine's new god alongside those of the state."32 The traditional religion is not to be forsaken just expanded to no longer be antagonistic to the powers of heaven, one being the Christian god. Further, this god has legitimated himself because he has given victory to Constantine and thus has sided with Roman rule. While a proChristian proclamation, the Edict does not elevate the Christian god above the traditional pagan deities but incorporates him into the traditional Roman pantheon for authorized worship. John Curran concludes about the Edict, "The highly visible and public ceremonies connected with these [pagan] cults would continue."33 The placating and incorporating of deities into the official pantheon was characteristic of Roman religion. J. Rufus Fears argues this point as it relates to the cult of Virtues in the Roman religious mentality. He writes concerning the worship of Concordia, As in the case of the Virtues worshipped at Rome, the cult of Concordia had its origins in a specific manifestation of its numen to the Roman People. Traditionally, the first cult to Concordia was established by Camillus to mark the restoration of civil harmony after the disorders surrounding the passage of the Licinian-Sextian laws. Historical or not, Plutarch's account accurately reflects the way in which such cults came into being. At the height of the crisis Camillus turned to the Capitoline Hill, prayed to the gods to bring the civil turmoil to an end, and vowed a temple to Concordia if the conflict should come to a happy end. When the issue was successfully resolved and the People and Senate reconciled, an assembly was held and the People voted to build the temple vowed by Camillus and to place it facing the Forum and place of assembly to commemorate what had transpired. In short, the introduction of the godhead Concordia into the ranks of the state gods was the result of a votum. If the deity addressed, Concordia, granted the requested benefit, civil peace, then Camillus, as vovens and representative of the Roman People, vowed Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome," 69. Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome," 69. 33 JOURNAL OF THE NABPR 317 that the pledge offering would be made. When the newly invoked divinity manifested its beneficent power by establishing concord, the debt had to be paid, and the temple was then erected and dedicated; cult was established to the deity, now further defined by the spatial localization of her cult in a templum and by the temporal specification of a particular feast day.34 Along very similar lines was the worship of the Christian god instituted by Constantine. Under the patronage and promise of this god, Constantine experienced victory and restored peace. Eusebius even depicts Constantine before his battle with Maxentius considering what kind of god he should call upon to give him aid eventually deciding to venture his fortunes upon the Christians' god.35 As a result of victory, Constantine instates Christian worship alongside the authorized Roman religions. Constantine then goes about honoring the Christians' god for his benefits—ending persecution of Christians, restoring church property, building basilicas, honoring sacred sites. Conclusion What might all this say about the "conversion" of Constantine?36 In studies on Constantine, there have been a range of opinions represented by scholars concerning the genuineness of Constantine's Christian faith as well as his political agenda. Jacob Burckhardt more than 150 years ago set forth the thesis that Constantine was a political opportunist who exploited the Christian religion for his own imperial purposes.3 On the other hand, others have in some measure accepted the Eusebian portrait of Constantine as a genuine Christian convert who embraced the mission to Christianize the Roman Empire over the course of his reign.38 Many have seen this process as gradual in conjunction with the progressive stages of Constantine's acquisition of power. Thus as Constantine's political power grew so did his opposition to paganism.39 Still others like 34 J. Rufus Fears, "The Cult of Virtues and Roman Imperial Ideology," ANRW 17.2:833-34. 35 Cf. Vit. Const. 1.27.2. 36 Thomas G. Elliott, "Constantine's Conversion: Do We Really Need It?" Phoenix 41 (1987): 420-38, has argued that Constantine had converted to Christianity before 312 C.E. prior to his encounter with Maxentius. 37 Jacob Burckhardt, The Age of Constantine The Great (trans. Moses Hadas; Berkley: University of California Press, 1949). The original edition, Die Zeit Constantin der Grossen, was printed in 1853. 38 See, however, Storch, "The 'Eusebian Constantine,' "155. Storch argues that Eusebius's panegyrics do not provide conclusive evidence of the genuineness of Constantine's Christianity. Eusebius's rhetoric is taken from themes traditional to Roman imperial discourse. 39 Cf. Thomas G. Elliott, "The Language of Constantine's Propaganda," TAPA 120 (1990): 349-53; Charles M. Odahl, "God and Constantine: Divine Sanction for Imperial Rule in the First Christian Emperor's Early Letters and Art," CHR 81 (1995): 327-52; Graham Gould, "What Did Constantine Do For Christianity," in Decoding Early Christianity: Truth and Legend in the Early Church (ed. James Leslie Houlden; Oxford: Greenwood World Publishers, 2007), 125-27,130; Timothy D. Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), 44,48-49; Hans A. Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine (Lancaster Pamphlets; New York: Routledge, 1996), 23, 28. Gould goes so far as to assert 318 PERSPECTIVES IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES Harold Drake, while not denying the genuineness of Constantine's conversion to Christianity, have argued that Constantine's political policy was one of relative tolerance that attempted to create a neutral public space for both Christians and pagans.40 What light might the preceding argument shed on this range of opinions? First, Constantine's imperial policy makes clear that Constantine favors Christianity and becomes its most powerfiil patron. He appears by Eusebius's accounts to be interested in Christian affairs and the unity of the churches across his empire. Constantine enters into the both the Donatisi and Arian controversies. Further his advocacy for Christianity appears to grow, especially after his conquest of the East.41 Second, the so-called Edict of Milan is both a political solution and act of devotion by Constantine. The god who gave Constantine victory must be honored. He has shown himself to exist and be worthy of worship. Roman tradition had allowed for newly recognized deities to be incorporated and honored in the traditional Roman religion when they had showed themselves to be beneficent towards Roman rule. By incorporating the Christian god into the authorized religions of the Roman Empire in a traditional Roman manner, Constantine was able to maintain devotion to the Christian god without alienating the majority of the Empire and especially ruling elites who remained pagan.4 Thus, Clifford Moore points out that from the Augustan settlement through three centuries of Roman rule "to many pagans it seemed that the safety of the state and the preservations of a civilization depended on the maintenance of religion with which their national life had been so intimately united that separation appeared utter ruin."43 With such a strong emphasis upon the importance of traditional religion among the imperial citizens, Constantine authorizes Christianity (as well as that Constantine had a divinely appointed mission to convert his subjects to Christianity (131). Barnes states that the apparent ambiguity of Constantine's Christian allegiance at the beginning of his reign was due to his deliberate, cautious, and shrewd changing of the imperial traditions over time, not due to lack of personal convictions (48-49). Pohlsander does express some caution in his claims about Constantine's conversion (23-24). 40 Harold A. Drake, "Constantine and Consensus," CH 64 (1995): 1-15. See also idem, 'The Impact of Constantine on Christianity," in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine (ed. Noel Lenski; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 121-22. Drake has aptly stated that the question we ought to ask is not whether Constantine became a Christian but what type of Christian did Constantine become (112). 41 Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome," 72-76. 42 Throughout the fourth century the Roman Senate remained for the most part pagan (cf. Clifford H. Moore, "The Pagan Reaction in the Late Fourth Century," TAPA 50 [1919]: 128-32). Constantine never seemed to divorce himself completely from traditional Roman religion or at the very least always showed exceeding tolerance for it. For instance, through the end of his reign he remained the Pontifex Maximus (Zosimus 4.36.4). This office made him head, not over Christian religious infrastructure, but over the state cults. He only banned malicious, manipulative magic not beneficial magic (cf. Lee, "Traditional Religions," 172 and Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient cults of Rome," 70). From 319-321 CE., Constantine continued to permit public divination while disallowing its private observance—a policy implemented by previous emperors (cf. Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome," 70). 43 Moore, "The Pagan Reaction," 127. JOURNAL OF THE NABPR 319 other religions) in a way that fortified and affirmed the traditional Roman reli44 gion. What then can we conclude about Constantine's conversion and political policies from our examination of the so-called Edict of Milan? First, Constantine was advocating the acceptance of the Christian god in terms of traditional imperial ideology. Augustus over three centuries earlier had identified his victory at Actium with Apollo. Constantine in like manner identified his victory over Maxentius with the Christian god, while not denying the traditional Roman pantheon as a result of this victory.45 From this perspective we then cannot talk about the conversion of Constantine, if what we mean by "convert" is that Constantine denied his pagan traditions and embraced singly the God of Jesus Christ. Second, the argument of this article also furthers, in some measure, Harold Drake's conclusions about Constantine's imperial policies. He writes, "Constantine's goal was to create a neutral public space in which Christians and pagans could both function, and that he was far more successful in creating a stable coalition of both Christians and non-Christians in support of this program of 'peaceful co-existence' than has generally been recognized."46 The imperial rhetoric of the pax deorum embodied by the so-called Edict of Milan created this "space" for both Christians and pagans on the basis of traditional Roman religious grounds. With Constantine and the issuing of the Edict of Milan, Christianity "entered into the complex of imperial religious life."47 Christianity thus gained a foothold in the affairs of imperial Rome that it did not easily relinquish, and imperial ideology found its way into Christian theology and history. 44 Interestingly, Robert M. Errington, "Constantine and the Pagans," GRBS 29 (1988): 309-18, has argued that Constantine's letter in 324 CE. to the Christians in the eastern provenances was clothed in Christian rhetoric in order to advocate a tolerance for pagans by rescinding an initial ban on pagan sacrifices. 45 Christopher Coleman (Constantine the Great and Christianity: Three Phases: The Historical, the Legendary and the Spurious [Studies in History, Economics and Public Law 146; New York: Columbia University Press, 1914]) rightly observes that Constantine's Christian convictions were not theological or moral but in identifying his fortunes with the Christian god (86). Well known is the fact that coins minted during Constantine's reign continued to display traditional images of Roman deities. 46 Drake, "Constantine and Consensus," 7. 47 Coleman, Constantine the Great, 95-96. ^ s Copyright and Use: As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the copyright holder(s)' express written permission. Any use, decompiling, reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a violation of copyright law. This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission from the copyright holder(s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of a journal typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However, for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article. Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available, or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s). About ATLAS: The ATLA Serials (ATLAS®) collection contains electronic versions of previously published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association (ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American Theological Library Association.