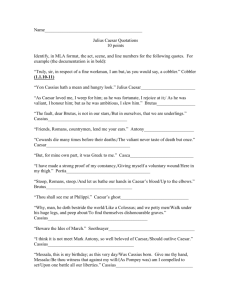

Julius Caesar Act 1, Scene 2 notes (from where we left off on Friday

advertisement

Julius Caesar Act 1, Scene 2 notes (from where we left off on Friday) 1.2.43-46 – B. “veiled his look” and instead of speaking of or sharing his conflicting emotions (presumably about conflicting loyalties to Caesar and to the Republic) he turned inward and adopted a seemingly stoic posture, yet he is in fact “vexed.” Nevertheless, and perhaps most problematically, Brutus doesn’t see that the issue vexing him is NOT merely his own concern (“only proper to himself”) but a concern that could affect the public, one that should be spoken aloud in a public, perhaps political forum (rather than hidden and then acted upon in secret) > This initial characterization of B. ushers in the contrast of B.’s stoicism to C.’s understanding of emotions and C’s ability to use these to his political advantage, esp. where the general public/commoners are concerned. They are, in this sense, foils. 1.2.57-77 Mirror metaphor – Brutus is unable to “see himself” and Shakespeare may be indicating that this lack of self-knowledge - perhaps in part due to his reliance on a stoic position that ignores the inward life in favor of logic, reason and principles – leaves Brutus vulnerable to manipulation. Cassius, in the manipulation, attempts to fill up this missing “knowledge” with flattering reports of how the people view Brutus, flattery which B. may be vulnerable to because he discounts the value of emotions yet, as a human being, is nevertheless susceptible to them Question is: Would a person with more "self-knowledge" – or perhaps “human knowledge”, ie knowledge of human nature, be less likely to be deceived? Or, do we learn nothing from knowing ourselves, except perhaps that we are vulnerable to deception? 1.2.67-68 – Cassius flatters B. with reports that many of the most respected people see B. as worthy and a good leader (they wish Brutus could see himself as they see him, presumable because this would mean he’s accept that role), but even more importantly appeals to B’s sense of honor and duty to the Republic by mentioning that the people are “groaning underneath the age’s yoke” (yoke is what shackles beasts of burden, like oxen, to a cart or plow), an appeal that suggests B must replace Caesar to unburden the people of Rome. 1.2.71 – “That which is not in me” – Brutus doesn’t see himself as a leader, but Shakespeare may also be suggesting that that which a leader must to do be successful – the Machiavellian idea of a good leader who can rule firmly and even dictatorially in the interest of the stability of the state, a leader who will put down insurrections, abandon principles if necessary in the interest of efficacy – is not in B. Question is: is that a good thing or a bad thing? He isn’t corrupt, but is he too principled? Can one be both noble and pragmatic? 1.2.74-76 – Cassius offers to show Brutus that part of himself his doesn’t yet know – denotatively he’s referring to B’s leadership qualities/the people’s justified trust in and affection for B (in the name of his attempt to flatter B), but Shakespeare may also use this line to suggest that Cassius will in fact reveal to B. by convincing him to join the conspiracy a part of himself he did not know he had: the capacity to commit murder of Caesar, to whom he was loyal and whom the people do love. 1.2.85-86 – “I do fear the people choose Caesar for their king” – ironic! Denotatively B is saying he’s fearing C will become a king, against the principles of the Republic, but the line also says he fears the “people choose”, which seems to run counter to the very principles he associates with the Republic: the will of the PEOPLE, the CHOICES of the PEOPLE being honored. 1.2.92-96 – Expresses B’s noble concern for the people and the importance of honor to him (perhaps overly important so as to blind him to pragmatic concerns/dangers?). If whatever Cassius wants to say to him concerns the general public, honor and death are the same to him, ie honor is worth dying for. 1.2.99 – “Honor is the subject of my story” – i.e. killing Caesar to restore honor to the Republic? Or perhaps also Cassius’s own personal honor, since he’s clearly piqued by Caesar being supposedly inferior yet politically more powerful than he 1.2.101-138 – Presents Cassius’s argument that Caesar is no better than the rest of them – ie he’d rather die than have to be “in awe” of, have to ‘worship’ a “thing” like Caesar, because like Caesar, they are born free (not slaves to a king), are equally strong and hardy. In fact, Cassius recalls instances of Caesar’s inferiority, his weaknesses relative to Cassius: *the swimming contest and the epic simile comparing Cassius to the Trojan war hero Aeneas who had to carry infirmed father Anchises (Caesar) to safety serves to show Caesar as weak and Cassius as heroic; Cassius clearly resents having to bow to Caesar (130-131) – jealousy? *Eye and mouth/speech comparisons: in public Caesar inspires fear and respect, in private his weaknesses show (dull eyes with fever, trembling lips begging for drink/water >Shakespeare is highlighting the discrepancy between the appearance, the image of Caesar and the reality that Caesar is just a man, not a god. > Cassius uses this contrast between image and reality to show that Caesar’s claims of greatness that are the basis for his political power and move to be king are unfounded. 1.2.142- Image of the Colossus suggests that Romans, Cassius and Brutus included, are like children grabbing onto daddy’s legs; dishonorable image of men as little children. Colossus also metaphor for Caesar’s rule/potential rule as king: tyrant 1.2.46-148 – Cassius argues that it is not fate or divine will that has made Caesar so powerful and them so subordinate, but rather their own inaction (the fault lies in “ourselves that we are underlings”). This is a call to action, and appeal that assumes something can be DONE to stop Caesar (and Cassius will soon propose what that is). 1.2.149-159 – Now Cassius appeals directly to Brutus through the comparison between B and Caesar’s names – CAESAR no better than Brutus. Irony in the line “’Brutus’ will start a spirit as soon as Caesar” (156) – Caesar able to appeal emotionally to the people – can Brutus with his reasoned stoicism? 1.2.159-166 – Now Cassius appeals to the noble Republican tradition in Rome that until now “made room” for more than one ruler, ie was an honorable Republic rather than a one-man show. 1.2.167- 170 – now Cassius appeals to Brutus’s sense of family honor, since it was Brutus’s ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, who founded the Roman Republic in 509 BC after driving out the last of the Tarquin kings. Cassius claims that Brutus’s ancestor preferred the devil to a king, insinuating that Brutus should feel the same (and get rid of Caesar). 1.2.171-184 – Brutus basically tells Cassius that he will think about what he’s said and that they’ll find a time to talk about it again, at which point he will give him a reply. He then adds that he would rather be a common, presumably poor and unimportant villager than to claim to be a son of Rome (as he is) under the conditions that are likely to be coming, suggesting that he is very concerned about the prospect of Caesar being king. Note that Shakespeare emphasizes that this is not yet the case, but only a possibility that Brutus thinks is likely (that Caesar will be crowned king). Is it okay to act to prevent something from happening if it’s not 100% certain that it will happen? (Caesar becoming king and being a tyrant in that role) 1.2.202-205 – Caesar fears Cassius because he looks “hungry”, ie not satisfied like men who are fat and sleep soundly, ambitious. His observation that he doesn’t like the idea that Cassius thinks too much suggests that Caesar would prefer satisfied, complacent, perhaps even dumb people around him who won’t challenge him. 1.2.208-222 – Caesar is saying that he doesn’t fear Cassius, because he (Caesar) isn’t a coward. He claims that because he is Caesar he tells what is to be feared, not what he fears. BUT, if he were to be one who experienced fear, he would fear Cassius because Cassius is not satisfied, sees too much, can’t be distracted with entertainments and distractions that normal men enjoy. The deafness motif here is important – although the character is literally deaf in one ear, Shakespeare also suggests that Caesar is, ironically “deaf” to the threat of the senators, “deaf” to their demands, while he “hears”, ie understands the common people. Conversely, the conspirators are “deaf” to the populist will. Perhaps Shakespeare is expecting that those in power need to “hear” both in order not to fall/fail? 1.2.245-261 – Casca recounts how each time Antony offered Caesar the crown, Caesar refused it, yet Casca thinks Caesar wanted it and was in fact just “playing” the crowd – the crowd of plebians (commoners) cheered each time Caesar refused it, presumably approving of his modesty/ apparent hesitation to take on such a role (he’s one with the peeps, after all). If this is a sign of political “playing” or gamesmanship, Caesar’s a master, for in seeming to not want the crown, the likelihood that the commoners will want him to accept it later is higher (“Oh no, I couldn’t possibly…well, if you insist”). Note Casca’s scorn for the commoners and their approval of Caesar – he characterizes them as brutes, animal-like, who stink so much they supposedly caused Caesar to swoon (when in fact it was an epileptic seizure). His little joke about not laughing at Caesar’s hesitation to accept the crown (which Casca thinks is feigned) for fear he would swallow the stench punctuates his attitude toward the commoners and toward Caesar’s “playing” them. 1.2.267 – Cassius’ joke that it is they, not Caesar’s who have the “falling sickness” is obviously a pun that suggests they – the otherwise powerful citizens of Rome – are “sick” because they “fall” before Caesar (“servile fearfulness”) and have fallen by letting Caesar have so much power. 1.2.269-286 – Casca compares the Roman people’s reactions to Caesar to the way an audience would cheer or jeer actors at the theater (very different from theater today; back then the theater was not considered to be a “high class” affair, and common people often shouted things at the stage). This comparison suggests A) that the common people are gosh, low class, easily swayed and B) that Caesar is “playing” them by acting a part that will please them. Casca continues with this characterization of Caesar as a clever play actor who convincingly fools and manipulates the people – dramatic gesture of offering for them to cut his throat (he’d sacrifice himself for the people), after he comes to he plays the pity card which elicits sympathy from the crowd. Casca sums up by saying Caesar is such a good actor/clever political player that the people would have forgiven him of anything, even if he had stabbed their mothers, suggesting the people are blind and unconditional in their support of Caesar. 1.2.289-294 –Cicero, another senator, apparently wasn’t buying Caesar’s “play” at modesty and weakness, and he made some sort of joke, which Casca didn’t hear/understand, but other senators there did. 1.2.295 –Casca then reports that the tribunes Marullus and Flavius whom we met in Scene 1 were punished for removing scarves (decorations for honoring Caesar) from the statues. This demonstrates that Caesar deals harshly with political opponents and spurs fears of his consolidation of power among the three here. 1.2.309-314 – Cassius explains that Casca, in acting in a stupid manner is actually politically clever; in appearing to be a “regular” stupid guy (the “sauce”) he is able to make that which he says or wants to get done easier to “digest” – his manner is disarming, but this allows him to win people to his side (compare to the “folksy” presidential candidates today). What Casca appears to be isn’t what he is (a favorite Shakespeare motif of appearance v. reality). 1.2.319 – “think of the world” is Cassius’ attempt to appeal to Brutus’ sense of honor (think of the “general” good”) so B will join the conspiracy 1.2.320-324 – Cassius’ soliloquy after Brutus’ exit cements the suspicion that Casssius is cunning and devious. Shakespeare uses a blacksmithing metaphor that compares Brutus’ honor to “mettle” (temperament, but originally the word comes from “the alteration of metal”) that can be bent by Cassius (the “blacksmith” in the metaphor), suggesting that Cassius plans to exploit Brutus’ sense of honor to his own ends. Cassius admits that Brutus is noble, but that this nobility can be “wrought”, ie beaten out or shaped by hammering, away from what it would normally do or consider correct. Cassius goes on to say that noble people should only associate with others who are noble, since no one is so strong that they can’t be “seduced” or swayed into doing something that is against their principles when in the company of a good manipulator/seducer (like Cassius). Cassius goes on to say that if their roles were reversed and Brutus were trying to influence Cassius, Brutus would be unsuccessful (Cassius has a big ego? Or is it Shakespeare suggesting that the ignoble, more Machiavellian types have stronger wills?). Here is where Shakespeare makes it clear that Cassius is not an honorable man, that he is intentionally trying to exploit Brutus’ sense of honor and duty to the people of Rome, but Shakespeare doesn’t go so far as to necessarily completely vilify Cassius; if Brutus is an honor-and-principles-before all else kind of guy, Cassius may be an ends-justify-themeans Machiavellian figure. Shakespeare makes Cassius’ manipulative, ignoble tactics perfectly clear when Cassius says he is going to forge numerous letters (in several hands) from Romans to Brutus in which Brutus is praised and Caesar’s ambition is alluded to and toss these letters into Brutus’ window – Cassius’ reasoning is that if Brutus thinks the people of Rome want him to act, he will likely respond. Either Caesar will be unseated (assassinated) or worse days are in store for “us” ( for the conspirators? All Romans? That is the question….).