Hecuba Study Guide - Westminster College

advertisement

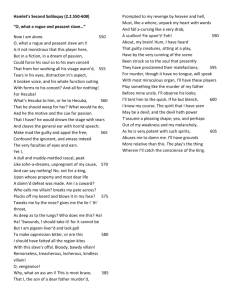

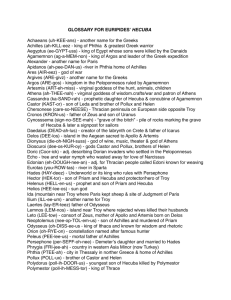

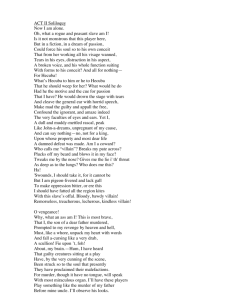

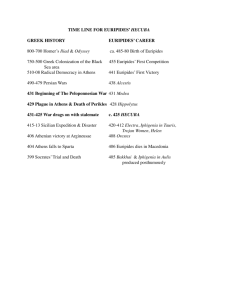

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A STUDY GUIDE FOR EURIPIDES’ HECUBA ! ! ! BY ! JAMES T. SVENDSEN I BACKGROUNDS MYTHIC: “The survival into captive slavery of Hecuba, queen of Troy, her further misery in seeing or learning the cruel deaths or slavery of all her family, and her own grotesque end, transformed into a bitch, were perhaps all unvarying facts of myth; they became so after Euripides. The poet inherited from the Epic, Lyric and perhaps earlier Tragic traditions differing accounts of Polyxena’s death, including her sacrifice to honour Achilles; but the emphasis in Hecuba on the girl’s willingness to die seems to be his innovation, like the particular role of Polydorus; and he appears to have invented Polydorus’ murderous host Polymestor for himself. Euripides’ conception of the play, bringing together in their remarkable effect on a previously broken and passive Hecuba the two successive deaths of her two children, had caused, it seems, another innovation: the setting in the Thracian Chersonese. The setting in Thrace stands together with the invention of Polymestor; he can be as freely barbarous as Euripides’ theatrical imagination requires.” ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! C. Collard HISTORICAL: “Hecuba dates from the 420’s, from the first decade of the great Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and their various adherents - the war recognized by its participants as unprecedented in scale and importance, a war whose course and conduct seemed to many of them to imperil almost everything that was fixed in standards of behavior. Hecuba is a product of the war’s uncertainties. It is tragic in its view of Hecuba suffering from the inescapable consequences of Paris’ Judgment and from man’s selfish and unpredictable cruelty; it is more unsettling for its audience in what those consequences and that cruelty provoke in Hecuba, her revenge, than it is reassuring about nobility and resilience amid such tragedy.! ! ! C. Collard DRAMATIC: “ Hecuba was first performed in about 424 BCE, some ten years before Women of Troy. It comes at the mid-point of Euripides’ career, in his most prolific period. Like Women of Troy, it has nothing in common with the kind of tragedy described by Aristotle. It belongs to another group ignored by him: plays which explore the character of an individual driven to extreme behavior by great suffering.... The style of Hecuba is remarkably rhetorical. It manner is almost as self-conscious as that of (say) Racine’s Britannicus, and there is a large amount of music and distracted song. Dons down the ages have complained that Hecuba is broken-backed, that it is artistically incompetent to write a first half in which your central figure is all grief and a second half in which she is all rage. This may appear to be the case in the study, but in the theatre -as in real life - it can seem an entirely plausible way for someone of this character, in these circumstances, to behave. Apparent oddity, in fact, both mirrors human experience and ‘makes’ the play.” ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kenneth Macleish II PLOT SUMMARY “Troy has fallen to the Greeks, Hecuba and the other captured women have started their journey to Greece and have paused in the land of Thrace, where Polymestor rules. There Polydorus, Hecuba’s youngest son, has been sent for safety but was murdered by Polymestor as soon as he heard the news of Troy’s fall. Polydorus’ ghost speaks the prologue. The chorus inform Hecuba that the Greeks are considering, whether to sacrifice her daughter Polyxena as an offering to the dead Achilles. Odysseus and Hecuba debate the fate of her daughter, Polyxena entering to say that she will die gladly rather than endure the life of a slave. Talthybios, the herald of the Greeks, describes how she died nobly, and Hecuba asks that she be allowed to give Polyxena a proper burial. A servant girl brings in the body of Polydorus which they have found floating in the sea, and, her grief now doubled, Hecuba asks Agamemnon to allow her to take revenge on Polymestor. Polymestor and his two sons are enticed into the women’s tent, where he is blinded and his sons murdered. Agamemnon judges a final debate between Polymestor and Hecuba and finds for Hecuba. Polymestor predicts the imminent demise of Hecuba as Odysseus’ ship returns to Greece.” ! ! Storey & Allen The plot thus can be viewed as a 1) bipartite action with the tragic death of Polyxena followed by the Hecuba’s successful revenge on Polydorus; 2) a tripartite action focusing on Hecuba’s three debates with Odysseus, Agamemnon and Polydorus; and 3) an action alternating scenes in iambics (e.g. monologues and debates) with musical scenes (arias, duets and choral odes). III CHARACTER: “And what of Hecuba herself? This is one of the great roles of Greek tragedy. She enters supported by her women, and she faints, falling to the ground on her back. Yes it becomes increasingly hard to think of her as a victim. It is not simply because she can talk with such intellectual reach and energy. She can even find some comfort in Polyxena’s courage.In fact the first part of the play may have led us to believe that she will succeed in reconstructing herself - in raising herself from the ground - in a positive way by learning through suffering. If that is our expectation, we shall be seriously disappointed. Whatever sympathy the audience may feel with Hecuba’s motivation in her treatment of Polymestor, the language of the play is insistent that a deed has been done, and Hecuba herself insists on the primacy of deeds over words. What she has done surely affects the way in which we now view her. Thus it is scarcely surprising that the general consensus among critics is that Hecuba’s prophesied transformation into a dog is in some ways a reflection of the dehumanization she has suffered during the action of the tragedy.”! ! ! ! ! ! ! James Morwood IV THEMES “The play is a staging ground for many familiar Euripidean themes and techniques: the opposition between virgin and mother, slave and free, Greek and barbarian, public and private, enemy and friend, male and female, beast and human; the contrapuntal ironies of shifting roles and relationships that involve forms of doubling, identification, and exchange among all the characters.”! ! ! ! ! Froma Zeitlin “Freedom (and slavery) is clearly a major theme of the play. Agamemnon is in institutional terms the character that enjoys the greatest freedom, but morally he is the slave of the military mob. Hecuba, in contrast to the king of Mycenae, has no institutional power, but is prepared to demand that moral right prevail and then to act herself to vindicate it. But if everyone is a slave, how can Hecuba, who is a slave in the most literal sense be an effective moral agent? The answer is a nice paradox: those who are literal slaves with no future can still exert enough physical freedom to vindicate their moral convictions. Precisely because they are slaves, they have nothing to lose and therefore no vulgar self-interest to corrupt their morality.” Stuart Lawrence “Necessity (anagke) in various forms is an important feature of the play. Polyxena stresses its force, Hecuba tries to make play with it, the chorus refer to it, and the final words of the play, appropriately enough, are ‘Necessity is harsh’, 1295. There are more instances of anagke in Hecuba than in any other play by Euripides. Abstract necessity seems to be a substitute for more anthropomorphic deities in this play. “At one level, charis might simply mean gratitude, favors exchanged for favors given. This is the reading that provokes charges of Hecuba’s utter debasement as a woman who would traffic in sex and abandon her moral standards for the sake of revenge. But charis is also an erotic term, suitably used for the pleasures of the night. Gratification and gratitude here coincide in this network of human relations.” ! Froma Zeitlin “One of the most important contrasts in the play is between Greek and barbarian, a contrast which coincides with that between dynastic figures like the Trojan queen and princess and members of a democratically run commonwealth like Odysseus and Agamemnon. This contrast is exploited not only in explicit speeches such as that of Odysseus to Hecuba (326f.) but also in the way Greeks, Trojans and Thracians are portrayed. Around this distinction other political and ethical distinctions group themselves, so that the contrast invites us to look for a meaning larger than the accidents of race.”! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! David Kovacs “Tarkov is correct in observing the obsessively numerous references to children and lineage in the play.... He reads the theme of children in terms of what they are supposed to represent (innocence, hope, and progress) and reduces the moral tensions and dramatic intricacies of the play into a sentimental homily, a ‘sad lesson’ that teaches us that in hard and inconsistent times, the continuity of family relations fails to serve as a measure of ‘constancy and permanence’ or to sustain the idea of ‘ hereditary nobility.’ On the contrary, it seems that ‘the lesson of the play,’ if any, is that men ignore or destroy those bonds to their peril, a typically tragic pattern.” ! ! Froma Zeitlin Other prominent themes include fate/chance (tyche), rhetoric and persuasion (peitho), traditional Greek values of friendship/loyalty (philia), honor (time), glory/ reputation (kleos) and justice/revenge (dike). V DRAMATIC STRATEGIES “As we have seen, there are several unusual and significant features; in general it is noticeably full of lyric, which unleashes a good deal of emotion early in the play. The musical pattern of the beginning of the play thus runs as follows: anapestic monody by Hecuba, parodos by chorus in anapests, monody by Hecuba, lyric exchange between Hecuba and Polyxena and monody by Polyxena.” ! ! ! J. Mossman “At 273ff. Hecuba makes a formal supplication gesture to Odysseus. She refers to his supplication of her at Troy, and she makes the same gesture as she says he did, kneeling, clasping the (right) hand and her garment.... The scene with Agamemnon is in many respects a mirror-scene to that of Odysseus, and this is marked visually by the supplication at 752, which employs the same gestures as the earlier one: kneeling and clasping the right hand and chin. This visual similarity is intended to recall the earlier scene to the audiences’ mind and thus act as a bridging scene.”! J. Mossman “Several scholars have written about Euripidean debates and their internal structure, and in general it seems that the dramatist the formalities of these contests with some subtlety. In the first Odysseus, whose counsel prevails, speaks second, as do the majority of successful speakers in Euripides; but Hecuba, as the character who holds both our sympathy and attention, has the longer rhesis. Late in the play Agamemnon stands in the role of a judge, but, as in the first agon (debate), the second speaker Hecuba will carry the day.! ! ! ! ! ! ! J. Mossman “The chorus, then play a very important role in articulating and illuminating the action. The odes are not interchangeable or unconnected with their context like the interludes of later dramatists. They are also very beautiful poetry, and provide a great deal of the aesthetic pleasure which, though it can not be said to lighten the grim tone of the drama, enhances it greatly by providing a lyrical counterpoint to its events. That the chorus sympathize with Hecuba throughout the play is important, but cannot of itself imply that Euripides meant us to take the same view: they are not omniscient, though they can be one factor in the presentation of the play’s moral issues.” J. Mossman V INTERPRETATIONS “Like so many Euripidean plays, the tragedy of Hecuba is not the tragedy of an individual but a group tragedy, its apparently random and disconnected episodes bound together by a single, overriding idea, forced up in ever more inclusive complexity by the development of the action. Uniting the Hecuba, underlying Hecuba’s transformation, and joining persecutors and persecuted in a common tragedy is a bleak logic of political necessity, a concern that brings the Hecuba close to Trojan Women and Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue.”! ! ! ! ! ! ! William Arrowsmith “ The Hecabe presents a spectacle of suffering, rage, and revenge, endured and enacted by women, who, as Euripides realized, suffer first and most from war. So long as we live in a world all but defined by violence, Euripides’ Hecabe will offer compelling witness to the courage and solidarity of those who suffer most and a fierce challenge to the simplistic assurance that suffering is somehow for the better of us all.” R. Meagher “Hecuba acts in harmony with her retributive morality. But does she act in harmony with the implicit morality of the play? We have seen that no other character objects to her treatment of Polymestor. Therefore, as nasty as retribution is, it is much more acceptable to conventional Greek sensibilities than to ours. Even so, acts of revenge in Euripides tend to be morally unsettling, and even an ancient audience is surely meant to find this one so. The play therefore does not offer comfortable moral closure. Hecuba does what has to be done since no one else will act for her, and she acts out of moral outrage and a sense of utter loss, performing the final significant act in a life that would be henceforth meaningless.” ! ! ! ! ! ! Stuart Lawrence “ For this play is about the bestialization that violence produces. The animal imagery in not incidental but essential. Violence treats Polyxene as a sacrificial victim; it brings Polymestor to crawling like an animal; it turns the women to savagery and the queen into a hellhound. Agamemnon, Cassandra, and Polyxene are all victims of violence. Only Polyxene rises above the violence, and, as Arrowsmith puts it, ‘her death, futile in itself, exposes, by the quality of its commitment, the dense ambiguity of the moral atmosphere for those who cannot die.’ Even she cannot arrest the escalation of the violence; but once she is removed the degeneracy and degradation steep the scene like some foully increasing fallout and poison all they touch. It was happening in the Greece that Euripides knew, and his play was a warning and a protest.”! John Ferguson “It would be difficult to exaggerate the blackness of this play, or the horror of the closing scene, as three doomed protagonists exchange hatred and predictions of death and degradation. The watchword of Hecuba is ugliness, to aischron. By throwing aside the heroic, the play grapples directly with evil. Yet evil and pain in themselves are alien to poetry, since they carry with them the constant threat of grotesquerie, of the ludicrous that lies always so close to the horrible, or of a lack of proportion, grace, and measure.... Like the Sophistic itself, the play is both false and valid, empty and futile, yet filled with a demonic energy that is itself a celebration of the aspirations it mocks. In the end, Hecuba creates its beauty, not by ennobling what is ordinarily shameful/ugly (aischron), but of the very elements of the aischron itself.” ! ! Ann Michelini “Hecuba has been criticized for being persistently and defiantly rhetorical -it was criticized for being so even in antiquity. Its structure has been condemned as brokenbacked. Its stage effects are deliberate, and sometimes elaborate, variations on the common patterns of tragedy, and have been seen as lurid travesties of them.... In fact, Euripides’ Hecuba contains some of Euripides’ strongest writing. It should be admired for the brilliance and poignancy of its rhetoric, for the subtlety of its exploration of intellectual themes,and for its masterly evocation of pathos. It is innovatively and excitingly plotted and carefully structured, and it makes effective use of the visual resources of the Greek theatre. The chorus’ role is perfectly adapted to the play, and their odes are moving and powerful. It should stand in the first rank of Euripides’ work.” ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Judith Mossman “The Trojan women are the survivors of a vanished world of wealth, dynastic power, and traditional morality, a world where family and personal allegiance were important and where the gods stood surety for the sanctity of the basic human emotions of pity, gratitude, and honor. The fall ofd Troy brings these women into sharp conflict with those whose way of life is the polar opposite of these, and by destroying the city which upholds these values puts them to the test in the crucible of absolute powerlessness. It is in the light of this contrast - what we might call the heroic and the non-heroic in the political dimension - that the action of the play assumes its wider significance, the two halves of the play cohere, and the anachronistic speeches make their contribution to an artistic whole.”! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! David Kovacs “ Like all tragedies, Hecuba is a drama of human relations, involving friend and enemy, kin and nonkin. Like most, it is structured around the distinctions between the world of women and the world of men. It goes further, however, in several ways. First, gender relations are radically polarized in the distribution of power. Second, there is an increased complexity in the dynamics of these relations. Third, most notably, all human relations in the play are expressed and determined by the body, whether in contact or disjuncture, supplication or slaughter, embrace or lament. No other play forces upon us so insistently the sheer physicality of the self and its component parts: the head, face, cheek, neck, throat, eyes, breasts and bosom, hands, arms, flanks, knees, flesh and blood. Our attention is drawn to the body, upright or prone, vigorous or weak, naked or clothed, free or constrained, alive or dead.”! ! ! ! Froma Zeitlin