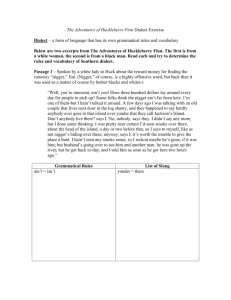

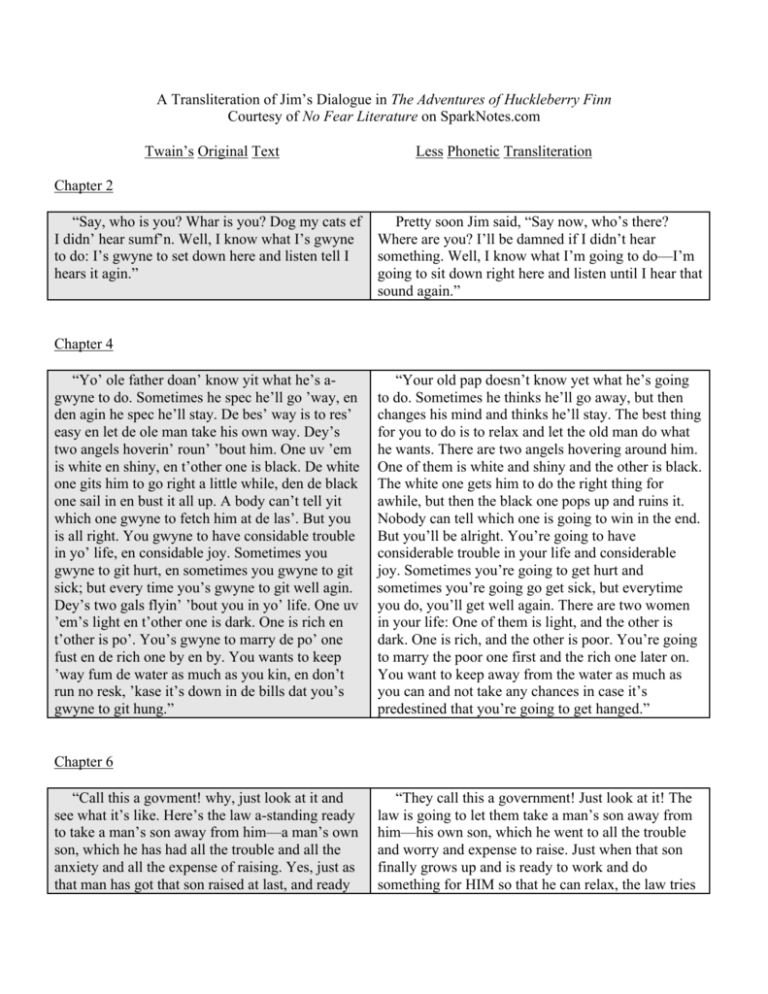

Easier-To-Read Dialogue for Huck Finn--ch. 1

advertisement