Ewing v. Goldstein and the Therapist's Duty to Warn in California

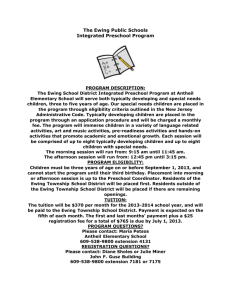

advertisement