IDENTITY THEFT: MAKING THE KNOWN UNKNOWNS KNOWN

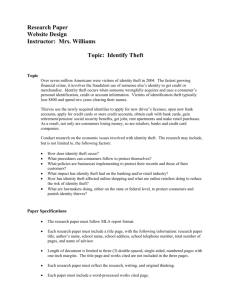

advertisement