Classics in Cultural Criticism

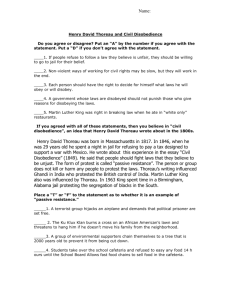

advertisement