Living in a Material Society By Cara Campbell I can understand why

advertisement

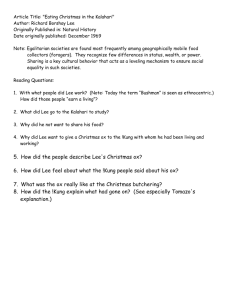

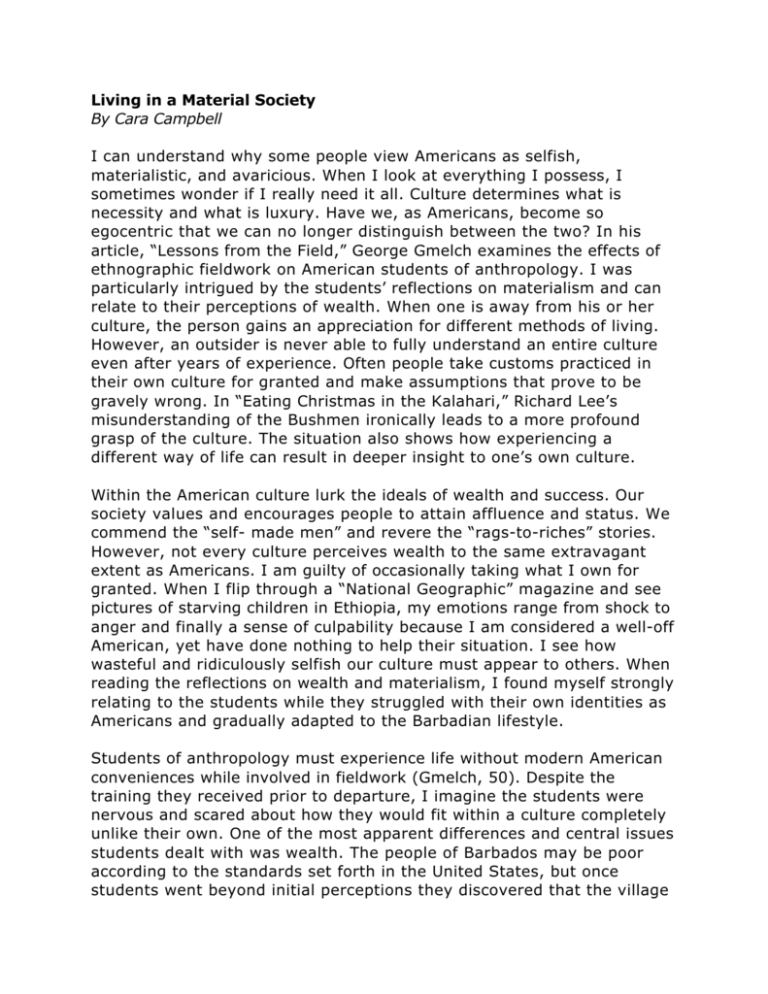

Living in a Material Society By Cara Campbell I can understand why some people view Americans as selfish, materialistic, and avaricious. When I look at everything I possess, I sometimes wonder if I really need it all. Culture determines what is necessity and what is luxury. Have we, as Americans, become so egocentric that we can no longer distinguish between the two? In his article, “Lessons from the Field,” George Gmelch examines the effects of ethnographic fieldwork on American students of anthropology. I was particularly intrigued by the students’ reflections on materialism and can relate to their perceptions of wealth. When one is away from his or her culture, the person gains an appreciation for different methods of living. However, an outsider is never able to fully understand an entire culture even after years of experience. Often people take customs practiced in their own culture for granted and make assumptions that prove to be gravely wrong. In “Eating Christmas in the Kalahari,” Richard Lee’s misunderstanding of the Bushmen ironically leads to a more profound grasp of the culture. The situation also shows how experiencing a different way of life can result in deeper insight to one’s own culture. Within the American culture lurk the ideals of wealth and success. Our society values and encourages people to attain affluence and status. We commend the “self- made men” and revere the “rags-to-riches” stories. However, not every culture perceives wealth to the same extravagant extent as Americans. I am guilty of occasionally taking what I own for granted. When I flip through a “National Geographic” magazine and see pictures of starving children in Ethiopia, my emotions range from shock to anger and finally a sense of culpability because I am considered a well-off American, yet have done nothing to help their situation. I see how wasteful and ridiculously selfish our culture must appear to others. When reading the reflections on wealth and materialism, I found myself strongly relating to the students while they struggled with their own identities as Americans and gradually adapted to the Barbadian lifestyle. Students of anthropology must experience life without modern American conveniences while involved in fieldwork (Gmelch, 50). Despite the training they received prior to departure, I imagine the students were nervous and scared about how they would fit within a culture completely unlike their own. One of the most apparent differences and central issues students dealt with was wealth. The people of Barbados may be poor according to the standards set forth in the United States, but once students went beyond initial perceptions they discovered that the village people “manage quite well on what they have...[and] are reasonably content” (Gmelch, 50). Unlike Americans, Barbadians do not equate happiness and success with the amount of monetary wealth one possesses. Initially, I was somewhat surprised to discover that students found villagers to be “more satisfied with their lives than are most Americans” (Gmelch, 50). Yet, after thinking about the concept, I recognize how much sense it makes. Perhaps Americans in general are not content because in the United States one is relentlessly encouraged to pursue wealth. Being “satisfied” in America would signify one’s resignation to a particular status level. After their fieldwork experience many students say they are “less materialistic” and “no longer take for granted the luxuries” (Gmelch, 51) found in American society. I am skeptical of this. I believe that students returned with new perceptions of wealth in the United States, but after they become accustomed to their old habits once again, they most likely reverted back to the traditional American mindset. A person cannot help being materialistic in America. It is a part of our culture that regretfully will not change. Another aspect of American culture is philanthropy. I believe that along with American wealth comes the desire to spread one’s fortune and give back to the community. Before reading “Eating Christmas in the Kalahari,” it never occurred to me that some cultures might perceive the benevolent act of gift giving as arrogance. Richard Lee was especially confused at the reaction he received from the Bushmen when he expressed his desire to provide the largest animal for the traditional Christmas feast. Lee simply wished to show his gratitude for the hospitality he was granted during his stay in the Kalahari. Acting in a typical American fashion, Lee was “determined to slaughter the largest, meatiest ox that money could buy, insuring that the feast and trance dance would be a success” (Lee, 16). I was astonished as I read the Bushmen’s reactions to Lee’s intentions. They blatantly insulted the animal Lee chose by referring to it as a “bag of bones” (Lee, 17). However, just as Lee’s impulse to find the largest animal and be successful reflects American values, the Bushmen’s mockery was characteristic of their own culture. Within the egalitarian society of the Kalahari, equality is necessary while arrogance is condemned. Even after living with the Bushmen for an extended period of time, Lee did not comprehend their practice of “insulting the meat.” After his humiliating experience with the Christmas ox, Lee saw how the Bushmen “refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride will make him kill somebody. So we always speak of his meat as worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle” (Lee, 21). Although Lee was hurt by the reaction he received to his generosity, the Bushmen’s “thoroughgoing skepticism of good intentions” (Lee, 21) caused him to reevaluate his perceptions of the culture and lead to a greater understanding of his own American identity. Every member of a culture is directly affected by the values and standards found within their society. I have seen how experience with different cultures can result in deeper insight to one’s own culture. In “Lessons from the Field,” George Gmelch shows how the perspective of his students was radically altered after living in poor villages without the comfort of American luxuries. Richard Lee portrays his humbling experience in “Eating Christmas in the Kalahari” and demonstrates that not all efforts of generosity are appreciated. Prior to reading these articles, I had not considered the extent of American materialism or the arrogance associated with gift giving. I think it is essential to recognize one’s own cultural views and why they exist while being tolerant and respectful of another’s perspective. If everyone embraced this principle it is possible that the world would be a less confusing and more enjoyable place to live Works Cited Gmelch, George. “Lessons from the Field”. Conformity and Conflict: Readings in Cultural Anthropology. McCurdy, David M. & Spradley, J. Boston: Macalester, 2003. Lee, Richard B. “Eating Christmas in the Kalahari”. Conformity and Conflict: Readings in Cultural Anthropology. McCurdy, David M., & Spradley, J. Boston: Macalester, 2003.