1 Booker T. Washington Rediscovered Lesson Plans/Exercises for

advertisement

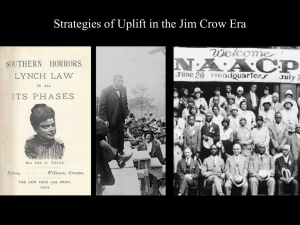

Booker T. Washington Rediscovered Lesson Plans/Exercises for Booker T. Washington Website Prepared by Michael Scott Bieze and Marybeth Gasman Chapter Four: Work 1. Booker T. Washington frequently combined words and images to express his ideas. Such an interaction, or rebus, of the written and visual languages has been interesting to cultural analysts in the Postmodern era. Philosopher Roland Barthes argued that understanding image and text relationships required analysis of three aspects of social context: (1) the historical moment, (2) the site of the text and image, and (3) the cultural formation of the reader. In 1903, Booker T. Washington illustrated his article “The Successful Training of the Negro” with several photographs by the prominent photographer Francis Benjamin Johnston. A. The Historical Moment: Describe the political and social issues of 1903 as they pertain to race, education, and labor relations. B. The Site of the Image and Text: What kind of magazine was The World’s Work? Who was the publisher? Where was it published? How large was the readership? What does the cover of this issue say about the magazine? C. The Cultural Formation of the Reader: What do you think is the educational background of the reader of the article? Which other works by Johnston would have been known to 1 the readers? How would that knowledge affect the way readers understand Washington’s message? 2. Key phrases such as dignity, resistance, self-determination, and racial uplift were frequently used by writers on race during the era of Booker T. Washington. One challenge facing students of the period is that these terms, like others, could greatly vary in meaning. In his 1896 article “The Awakening of the Negro,” Booker T. Washington employed one of his favorite phrases--“the dignity of labor.” Here, in four words, is the essence of Washington’s philosophy on nearly every idea on which he wrote. Many Washington’s critics argue that his brand of self-determination failed. V. P. Franklin writes: In each significant area of black life at the turn of the century, Washington enunciated a “conservative position” that was not only against black interests, but was also contrary to Afro-American cultural values. Self-determinist values that had developed among the black masses meant that black control of black institutions was valued and sought. To most people Washington appeared to be the captain as well as the “wizard” of Tuskegee and his support for black-owned business and other capitalistic enterprises through the National Negro Business League appealed to the self-determinist values of the AfroAmerican masses. But at the same time, Washington’s accommodating political positions 2 were opposed to the Afro-American cultural values of survival with dignity and resistance against oppression (Black Self-Determination, 182). A. What does Washington mean by the phrase, “the dignity of labor”? How does it link with the terms resistance, self-determination, and racial uplift? B. How does V. P. Franklin’s use of the word dignity differ from Washington’s? C. Read the following three chapters in Reading Booker T. Washington: (1) “Why Negro Business Men Should Go South,” (2) “Pensacola, a Typical Negro Community,” and (3) “The Negro Doctor in the South.” Do Washington’s writings on Black control of institutions represent accommodation or resistance against oppression? Why? 3. Edwin Markham’s widely published 1899 protest poem, “Man with a Hoe,” became a powerful symbol of the dehumanization of the agricultural worker in the New Modern era. Based on a painting by the French Realist Jean Francois Millet, it ignited controversy as soon as it was published. For some, the man with the hoe was the embodiment of the exploited worker. For others, the man with a hoe signaled a dangerous call to socialist labor reforms. Further complicating the poem’s meaning is that it was elaborately reprinted in publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, a highbrow publication. Man with a Hoe 3 Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground, The emptiness of ages in his face, And on his back, the burden of the world. Who made him dead to rapture and despair, A thing that grieves not and that never hopes, Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox? Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw? Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow? Whose breath blew out the light within this brain? Is this the Thing the Lord God made and gave To have dominion over sea and land; To trace the stars and search the heavens for power; To feel the passion of Eternity? Is this the dream He dreamed who shaped the suns And marked their ways upon the ancient deep? Down all the caverns of Hell to their last gulf There is no shape more terrible than this-More tongued with cries against the world's blind greed-More filled with signs and portents for the soul-More packed with danger to the universe. 4 What gulfs between him and the seraphim! Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him Are Plato and the swing of the Pleiades? What the long reaches of the peaks of song, The rift of dawn, the reddening of the rose? Through this dread shape the suffering ages look; Time's tragedy is in that aching stoop; Through this dread shape humanity betrayed, Plundered, profaned and disinherited, Cries protest to the Powers that made the world, A protest that is also prophecy. O masters, lords and rulers in all lands, Is this the handiwork you give to God, This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quenched? How will you ever straighten up this shape; Touch it again with immortality; Give back the upward looking and the light; Rebuild in it the music and the dream; Make right the immemorial infamies, Perfidious wrongs, immedicable woes? O masters, lords and rulers in all lands, How will the future reckon with this Man? 5 How answer his brute question in that hour When whirlwinds of rebellion shake all shores? How will it be with kingdoms and with kings-With those who shaped him to the thing he is-When this dumb Terror shall rise to judge the world, After the silence of the centuries? A. How does Booker T. Washington’s archetypal worker compare with the Man with a Hoe? B. There are parallels between Hearst’s printing of this worker poem and the appearance of Washington’s work in elite northeastern magazines. Why would a powerful capitalist print these works? 6