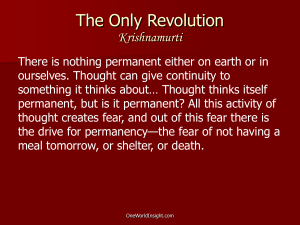

The Awakening Of Intelligence pdf

advertisement