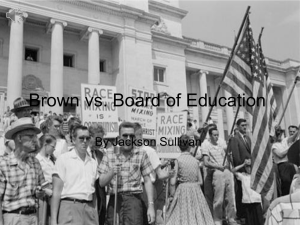

Separate but equal - Racial segregation in the United States

advertisement