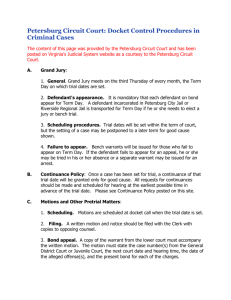

The Right to Counsel in Criminal Investigations

advertisement