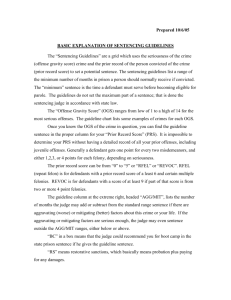

responding to the model penal code sentencing revisions

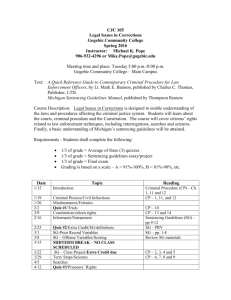

advertisement