PDF - University of Illinois Law Review

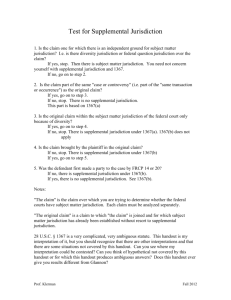

advertisement