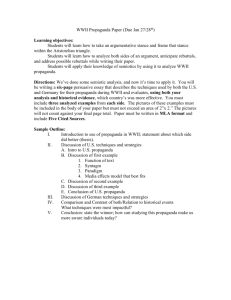

3. Issues in Argument

advertisement