Economic History Association

Cambridge University Press

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3875012 .

Economic History Association

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History.

http://www.jstor.org

THE JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC HISTORY

VOLUME65

SEPTEMBER2005

NUMBER3

A CompromiseEstimateof GermanNet

National Product, 1851-1913, and

its Implicationsfor Growthand

Business Cycles

CARSTENBURHOPAND GUNTRAMB. WOLFF

We develop a compromiseestimate of the GermanNet National Productfor the

years 1851-1913 based on four estimates from Hoffmann(1965) and Hoffmann

and Miller (1959) by recalculatingindustrialproduction,investment,home and

foreign capital income. Because differencesremainduringthe early decades, we

compute a weighted average compromise series. Economic activity is shown to

be higher than the older estimates suggest. The average growth rate is lower.

The average business cycle lasted five years, with high volatility in the early

decades. The typical Griinderzeitpatternof boom then prolongedrecession after

1873 can not be confirmed.

R eliable data are centralto empiricalresearch.Some of the most freI'%quently used data sets for economists are the national accounts

from which national product estimates derive. Historical national accounts for the nineteenthcentury are employed to describe and analyze

the industrializationperiod. They are also central for empiricaltests of

The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 65, No. 3 (September 2005). C The Economic

HistoryAssociation. All rights reserved.ISSN 0022-0507.

CarstenBurhopis AssistantProfessor,Institutefor EconomicandSocialHistory,University

of Mtinster, Domplatz 20-22, 48143 Mtinster, Germany. E-mail: burhop@uni-muenster.de.

Guntram

B.Wolffis SeniorResearchFellow,Centerfor European

Studies,UniverIntegration

sity of Bonn, Walter-Flex-Str.3, 53113 Bonn, Germany.E-mail: gwolff@uni-bonn.de.

We would like to thank J6rg Baten, Helge Berger, Jitrgenvon Hagen, Ulrich Pfister, Hans

Pohl, Albrecht Ritschl, RichardTilly, MartinUjbele,participantsof the researchseminarof the

Center for EuropeanIntegrationsStudies, and participantsat the Verein fir Socialpolitik conference 2002, economic history research seminar at the Humboldtuniversity, World Congress

of Cliometrics 2004, and three anonymous referees and the editor for many helpful comments

and suggestions. We would also like to thank Jutta Schmitz and Juliane Schraderfor research

assistance. Remaining errorsare ours. An earlierversion of this article was writtenwhile Burhop was research fellow at the Center for Development Research, Bonn University. Financial

support of that institute and of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft(Burhop) is gratefully acknowledged.

613

614

Burhopand Wolff

long-term macroeconomic phenomenon such as business cycles and

economic growth.

The bulk of research on Germanmacroeconomichistory during the

nineteenth century, long-term investigations of the German economy

since the nineteenth century, and international-comparativestudies

about macroeconomic patterns, are based on data from two seminal

contributionsby WaltherHoffmann and Heinz Mfiller and Hoffmann.!

These monographsinclude extensive estimates of the Germannet national product(NNP) from the income, output,and expendituresides for

the years 1850 to 1913. During the last four decades, these data series,

especially the expenditureseries from Hoffmann, found their way into

many international statistical handbooks and quasi-official publications.2 Taken from the original publications,as well as from the statistical handbooks,these series form the backbone of many writings about

Germanmacroeconomichistory. Studies of the Germanbusiness cycle

and investigations of the German growth performanceemploy Hoffmann's series.3

Although extensively used, the reliability of the data is often questioned. In fact, the data quality has been debated for at least two decades, by such scholars as Carl-LudwigHoltfrerich,Eckart Schremmer,

Rainer Fremdling, Albrecht Ritschl and Mark Spoerer, Rainer Fremdling and Reiner Staiglin,and CarstenBurhopand GuntramWolff.4 The

output, income, and expenditure series by Hoffmann have been criticized: the calculation of industrialproduction,the computationof capital stock and investment, and the estimation of capital income are central points of concern. Nevertheless, German national accounting

figures for the nineteenthcenturyhave not been re-estimated.

In this article, we contributeto the ongoing debate about the data

quality by presenting improvementsof all four available series. In particular, we improve the output series by calculating a new index of inHoffmann, Wachstum.

1Hoffmannand Mfiller, Volkseinkommen;

2

Hoffmann, Wachstum.For examples of handbooks, see Mitchell, InternationalHistorical

Statistics; and Maddison, WorldEconomy. A quasi-official publication is Deutsche Bundesbank, Deutsches Geld- und Bankwesen. However, one should note that the Hoffmann-Mtiller

income series builds on the official income series of the Statistische Reichsamt, which was

includedinto StatistischesBundesamt,Bevdlkerungund Wirtschaft.

3 On the business cycle, see Craig and Fisher, "Integration";Backus and Kehoe, "International Evidence"; and A'Hearn and Woitek, "More InternationalEvidence." On growth perRace and,

formance, see Metz, Zufall and Trend, Zyklus, Zufall; and BroadberryProductivity

How did the UnitedStates.

4Holtfrerich, Growth; Schremmer, Die badische Gewerbesteuer; Fremdling, German

National Accounts (1988) and German National Accounts (1995); Ritschl and Spoerer,

Bruttosozialprodukt;Fremdling and Stiglin, Industrieerhebung; and Burhop and Wolff,

Datenwahl.

CompromiseEstimate

615

dustrialproductionand by basing the index on a revised value of industrial output in 1913. In addition, we significantly enhance the capital

stock and net investment series, and we present new data about capital

income. Furthermore,we present a new series of net foreign capital income. Finally, we add new informationabout "indirecttaxes" to the income and output series, and we thus calculate four series representing

an NNP in marketprices. Despite our significant improvements,differences between the series remain, and we solve this problem in a second

step by computing a compromise estimate of Germany's NNP for the

years 1851 to 1913 as a weighted average of the four correctedoriginal

series.

The remaining parts of the article analyze long-term growth and

business cycles of the German economy employing the new compromise estimate. The revised data show a higher level of economic activity for 1851 as well as for 1913, but with a larger difference for 1851.

Thus, the average growth rate of the Germaneconomy was lower during the industrializationperiod. Moreover, the driving force of this

growth was a growing total factor productivity, which in turn was

driven by structuralchange from agricultureto industry. The business

cycles of the German economy had an average length of about five

years duringthe second half of the nineteenthcentury;the magnitudeof

cycles was weaker in the last quarterof the nineteenth and the early

twentieth century than before. Of special interest is our business cycle

dating for the 1870s: with the new data the well-known pattern of

"Grtinderzeit"-boomand "Grtinderzeit"-depressioncan not be confirmed.

DATA

The net nationalproductat factor costs or marketprices can be calculated in three ways: from the expenditure,income, and output sides. In

the national accounting scheme, the three approachesare based on the

expenditure,output, and income accounts and should lead to identical

aggregates.In Germany,national accounting startedin 1891, and up to

World War I only the income series were calculatedby the Kaiserliche

Statistische Amt (Imperial statistical office). The German economist,

Hoffmann, estimated in two seminal contributionsnational accounting

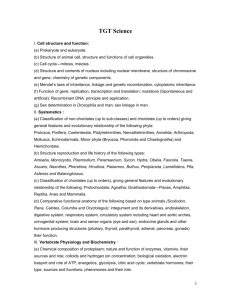

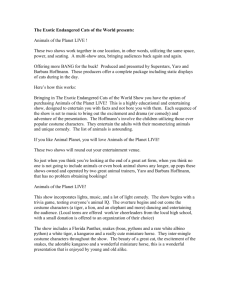

figures for Germany(see Figure 1).5 As can be seen, the four series differ significantly, because of estimation errors and because they represent differentnationalproductconcepts.

5 Hoffmann, Wachstum; and Hoffmann and Miller, Volkseinkommen.

616

Burhop and Wolff

4.00

SIHM

- - - - - I H - - - EH ---OH

3.75

3.50

3.25

3.00

;

2.75

2.50

2.25

2.00

T

16T

1r,

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE

1

COMPARISON OF FOUR ORIGINAL ESTIMATES OF REAL GERMAN NATIONAL

PRODUCTIN LOG OF BILLIONMARK, 1913 PRICES

Source: Hoffmann and Miuller,deutsche Volkseinkommen,p. 39 (IHM, Income Series); and

Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 505 (IH, Income Series), p. 825 (EH, ExpenditureSeries), and p. 459

(OH, OutputSeries).

Some time ago Fremdlingpointed out that there are large differences

in the levels of these series, and recalculationsfor the early 1850s indicate that Hoffmann understatedthe true level of economic activity in

Germany.6So far, however, Germannational accountingfigures for the

nineteenthcenturyhave not been re-estimated.7

The recent literaturepresents two approachesto the re-estimationof

historicalnational accounts. First, the "structure-approach"

of Christina

Romer applies statisticalrelationshipsbetween nationalaccountingsub6 Fremdling, National Accounts

(1988). and National accounts (1995); and Hoffmann,

Wachstum.Differences between the income, output,and expenditureseries are well known for

other countries, e.g., for the United Kingdom, see Nicholas Crafts, Recent Research; and

Greasley and Oxley, Balanced versus CompromisedEstimates.

7 Ritschl and Spoerer,Bruttosozialprodukt,presenta re-estimationfor the years 1900 to 1995.

Compromise Estimate

617

series from modem times to historical data.8 Second, the "new-dataapproach"of Nathan Balke and Robert Gordonuses additionalhistorical data to improve former estimates.9The second approachuses more

information,and it is thereforemore efficient than the first. We decided

In the following we discuss

to follow mainly the "new-data-approach."

the expenditure,the output, and the two income approachseries. Furthermore,we assess the quality of the four estimates and present our

improvedestimates.

The centralpiece of Hoffmann's book is the output-series,which we

label OH. It is based on a voluminous investigation of productionfigures for many sectors.10In general, outputseries are calculatedfrom the

productionside by adding up the net value added of the different sectors. However, value added data were not collected by the statisticaloffices. Hoffmann bases his estimates on output quantities, not values,

and employmentfigures. The calculatedproductionindex is linked to a

base measureof outputin 1913.

One majorproblem is the calculation of the industrialproductionindex by Hoffmann, which was criticized by Fremdling, and especially

Holtfrerich.1 Hoffmann transformsthe productionindices of 12 industries into a Germany-wideindustrialproduction index by multiplying

the 1936 net productionvalue per employed with the number of employed in the 12 industries using employment figures from census

data.12 He therefore assumes a constant relative industrialproductivity

for the subsectors duringthe years 1850 to 1959, the years covered by

Hoffmann's study. The 1861 employment census is used for the years

1850 to 1872, the 1882 census for the years 1872 to 1895, and the 1907

census for the years 1895 to 1913. Finally, Hoffmann estimated the

value of industrialproductionfor 1913 by multiplying the total industrial employment with the average industrialwage, and by adding the

productof the estimatedindustrialcapital stock and return-on-capital.13

He then applies his industrialproduction index to the 1913-industrial

Cycle. Another approachin this line of research is Solomou and

Balanced

Estimates.

Weale,

9 Balke and Gordon,Estimation.

10 Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 344, discusses the quality of his data. The data quality seems to

be good after about 1870.

1 Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 390; Holtfrerich, Growth; and Fremdling, National Accounts

(1988) and National Accounts (1995). For the interwar years, Ritschl, Spourious Growth,

critizised the calculation of output in the metal processing industry, which is based on labor

income and the assumption of a constant labor income share, not on productionfigures. This

means that a large partof the outputseries is constructedfrom income data.

12Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 389.

13Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 459.

8 Romer, Prewar Business

618

4.75

4.50

Burhopand Wolff

-

-

-

Hoffinann's Index

Corrected Index

4.25

4.00

3.75

3.50

3.25

3.00

2.75

2.50

2.25

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

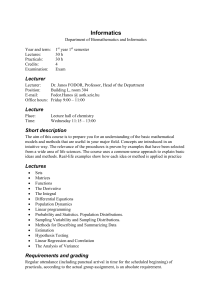

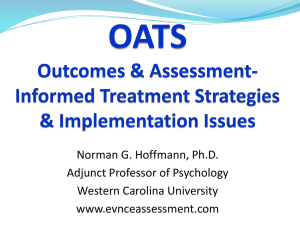

FIGURE

2

INDEX OF INDUSTRIALPRODUCTION,1851-1913. 1913 = 100, IN LOGS

Source: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 390.

productionvalue to calculate the value of industrialproductionfor the

years 1850 to 1913 in 1913-prices.14

We improve this method by using additional industrialemployment

data given by Hoffmann.'5Thus, data from the Zollverein-censusesof

1846 and 1861, and Prussian census data (for 1846, 1849, 1852, 1855,

1858, 1861, and 1867) are used.16 In addition, we linearly interpolated

the data instead of using stepwise constantemploymentmultipliers.Our

re-estimatedindex of industrialproductionis comparedwith the original Hoffmann-indexin Figure 2, the data are in the Appendix Table 3.

The main difference between Hoffmann's index of industrialproduction and our newly calculated one is the higher level of industrialpro14Wagenfiihr,Entwicklungstendenzen,p. 47, calculated an industrialproduction index for

Germany startingin 1860 by combining physical output series of 57 industries.His weighting

scheme is based on 1907 employmentand the amountof horsepowerinstalled. He conceeds on

p. 13 that his constant 1907 weights lead to an underestimationof industrialproductionin the

early decades, which is one of our majorconcernsregardingHoffmann's index.

15Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 196.

16

Germany-widedata on employmentare only available from Zollverein's censuses in 1846

and 1861. This informationis included.Furthermore,Prussiacovered around60 percent of total

employment, and comparisonof the Prussiandata with Zollverein data shows that the employment sharesof differentsectorswere quite similar.

619

CompromiseEstimate

4.20

4.00

3.80

Series

S4.00 OHHoffmann's

CorrectedSeries

3.60 S3.40"

S3.20

3.00

,"

2.80

,2.60 -

..-,

2.40 2.20

..

8

51TF

1

•1

i

I

1 1 -8

17

6I I 1

I

I

I I I I I1i9I

1

-

FF

1901

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE3

COMPARISONOF THE ORIGINALAND THE CORRECTEDNNP CALCULATEDFROM

THE OUTPUT SIDE, IN LOG OF BILLIONMARKS, 1913 PRICES.

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 459; and authors'own calculations.

duction in 1851. The annual growth rates are around 2.9 percent for

the new index, and 3.9 percent for Hoffmann's index. The difference

in levels can be explained by the different employment multiplier

scheme. For 1851 we take linearly interpolated employment weights

between 1849 and 1852. Hoffmann, on the other hand, used 1861

employment shares, thereby giving a higher weight to those

subsectors with higher employment growth in the period 18511861. Thus the level of physical production is weighted too strongly

for the fast-growing sectors. Thus Hoffmann's production index

should be smaller than our index, which is calculated with more accurate weights.17 This higher level of economic activity for the early

years conforms well to the views expressed by Holtfrerich and

17 A similar argumentholds for the jump in Hoffmann's industrialoutput index in 1872. Assuming that some industries grew faster than others over the entire period 1861-1882, then

these sectors will be underweightedin 1871, and overweighted in 1872 after the change to the

weights of 1882.

620

Burhopand Wolff

Fremdling.18 Especially Holtfrerich finds higher values of industrial

production.19

Because this article presents not only a new index of industrialproduction, but also new figures for the capital stock and the return-onalso changes, because it

capital, the value of 1913-industrial-production

is calculated by multiplying the number of employed with the average

wage and addingthe capital stock multipliedby returnon invested capital. Furthermore,output series in general give Net Domestic Productat

factor costs. We adjustedthe series by adding indirecttaxes to get NDP

at marketprices and then foreign income to get NNP. The change from

NDP to NNP is less than 1 percent. The change from factor cost to market prices is about 5 percent,which explains the main componentof the

level difference.Figure 3 presentsHoffmann's estimate and our new estimate of GermanNNP calculated from the output side. The corrected

series exhibits higher values than the old estimateand the differencebetween the two series increases over the course of the period. The level

increase is mainly due to adding a new estimate of indirect taxes, because the output series representsNNP at factor costs. We present all

series at marketprices for reasons of comparability.

For the calculation of an NNP estimate from the expenditure side,

Hoffmann estimates private and public consumption, net investment,

and exports and imports; we label this series EH.20 One of the main

problems is the calculation of investmentexpenditurefor the secondary

sector. In fact, Hoffmann estimates a capital stock index for Germany

based on capital tax (Gewerbekapitalsteuer)data in the GrandDuchy of

Baden, a small state in southwesternGermany.From these tax records

Hoffmann estimates the capital stock in Baden. He then extrapolatesit

to Germanyby multiplying it by around31, a number supposed to reflect Baden's share of total industrialemployment and its overall economic size. He derived the annual capital stock by multiplyingthe thus

calculatedindex value by a capital stock estimationfor 1913. This base

year estimation is independent from the Baden figures, because it is

18Holtfrerich,Growth;and Fremdlig,NationalAccounts(1988) andNationalAccounts(1995).

19The income

per industrialworkerin the Hoffmanndata appearsto be implausiblylow. It is

well below the NNP per employed, namely 555 M vs. 707 M in 1851. Our data, on the other

hand, give a laborproductivityof 1,165 M for the industrialsector, whereas the entire economy

has a productivityof 862 M. Only as late as 1908 Hoffmann's industrialworkersproducedmore

thanthe averageemployed in the economy.

20 Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 825. In fact, Hoffmann(Wachstum,p. 667) estimatedprivate consumption by subtractingexports minus imports, net investment and public consumption from

productionbecause there is little direct informationaboutprivateconsumption.Public consumption was estimatedby using governmentbudgets. Therefore,estimation errorsin the output series are transmittedto the expenditureseries.

CompromiseEstimate

621

based on additionaldata for the years 1925-1929.21 The yearly change

of the thus-calculatedcapital stock is the net investmentHoffmannused

in his expenditureseries. Therefore,the expenditureapproachexcluded

depreciation and leads to an NNP at market prices, not to a GNP.

Schremmer, based on the same and additional archival records, recalculates Hoffmann's base figures for Baden.22Schremmeraccounts

for changing tax legislation in this state, a fact left out by Hoffmann.23

He ends up with investmentfigures, which are significantlyhigher than

Hoffmann's figures for the years up to 1877. In other words, Hoffmann's NNP at marketprices is too low.

In addition, Hoffmann assumes that Baden's industrial structureis

representativefor Germanyas a whole. This is unlikely, as the "firstindustrialization"from the 1840s to the 1860s was concentratedin the

Ruhr-basinand in Silesia, two areas with a significant share of heavy

industry.Thus, Hoffmann's assumptionof an equal capital intensity of

the industrialsector in Baden and in Germanyis problematic.This assumption would make sense if the industrial employment structurein

Baden mirroredthe Germanstructureand if employment development

in Baden and in Germanywere equal. The use of employment census

data does not confirm these assumptions.24Baden's share of industrial

employment in Germanydeclined from 3.7 percent (1846) to 3.3 percent (1895); it then rose to 4.0 percent(1907). Even more problematicis

the structuralchange within the industrialsector. For example, in 1846

the employmentshareof metal productionand the metal working industry (Metallerzeugung-und -verarbeitung)was 19 percent in Baden, but

only 10 percentin Germany.In Baden, this shareremainedconstantuntil 1882, whereas in Germanyit rose to 15 percent. Thereafter,the employment share in Baden rose to 24 percent (1907), and in Germanyto

21 percent. Thus, the employment share of the capital-intensivemetal

industries doubled in Germany during these decades, but rose only

about 20 percent in Baden. On the other hand, textiles had an employment share of 29 percent in 1846-Baden, but 48 percent in Germany.

This changed by 1907: then, 20 percent were employed in textiles in

Baden, but 27 percent were in textiles in Germany.Thus, the growth of

capital-intensiveindustrialemploymentwas much strongerin Germany

21Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 240.

22 Schremmer,Die badische Gewerbesteuer.

23 Schremmer,Die badische Gewerbesteuer,focuses on data quality and says little about the

extrapolationof Baden datato Germany.

24 Employment data for Germany are given in Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 182. Comparable

data for Baden are available in Killmann, ed., Quellen, pp. 23-26, and pp. 58-87 for 1846,

1861, and 1875. For 1882 and 1895 see Kaiserliches Statistisches Amt, ed., Statistik (1899),

p. 252; for 1907 see: Kaiserliches StatistischesAmt, ed., Statistik(1910), p. 254.

622

Burhop and Wolff

than in Baden, and Hoffmann does not take account of this fact. To

quantify capital intensity, informationabout subsectoralcapital intensities is necessary.

Unfortunately,we do not have data on the capital intensities of industrial subsectorsin nineteenth-centuryGermany.Thus, we decided to use

informationfrom modem Germany.We assumed that the average relative capital intensity during 1970 to 1994 equals the relative capital intensity duringthe nineteenthcentury,using the capital intensity in construction as numeraire. For example, we assume for the chemical

industrya capital intensity of 5.9 times the capital intensity of construction.25Taking capital intensities from the late twentieth century might

not accuratelyreflect the economic structureof the period underconsideration.We checked the multipliersby derivingproxies of capital intensities from a study by Ernst Engel, who reportedthe horse power of

steam engines in different industriesfor the year 1878.26 Furthermore,

he estimated the capital cost of steam engines per horsepower and the

capital cost of connected machines. Thereby we were able to calculate

capital intensities. The Pearsonrankcorrelationwith the modem data is

0.89.27 We are thus confident that the use of modem capital intensities

will not seriously bias our results.

We compute an index value of capital intensity of subsector i as the

ratio of capital per worker in the subsectori relative to the construction

subsector'scapitalper worker

K

Ki

IL'

. Thisrelative

Kconstruction

ILconstruction

capital intensity i' is multipliedby the employmentshare of the subsector i in Baden respective to Germany. This yields the index value of

capital intensity of the entire industrial sector in Germany and in

25

The multipliers for the others subsectors are: 5.1 (building materials), 5.5 (metal production), 2.2 (metal works), 3.6 (textiles), 3.5 (leather and paper), 1.1 (clothing), 2.1 (wood), and

3.8 (food). The relevant data on employment and capital stock were made available from the

StatistischeBundesamtand are availableon request.

26

Engel, Das Zeitalterdes Dampfes.

27

We comparedour estimates with estimates taking British capital intensities for 1920 (data

are from tables 101 and 130 of Feinstein, Statistical Tables). The Pearson rank correlationbetween Germancapital intensities of 1970-1994 and British intensities of 1920 is 0.65. As another robustness check, we used data from the 1936 industrial census (Reichsamt ffir

WehrwirtschaftlichePlanung, Deutsche Industrie- und Gesamtergebnisse,pp. 25-29, 44-55).

We took the publishedratio of capital income to total income per subsectoras a proxy for capital intensity of the subsectors.These intensities give a Pearsonrankcorrelationwith the modem

German data of 0.55. Fremdling and Stiglin (Industrieerhebung,p. 422) point out that these

census data are distortedbecause of military-strategicconsideration,which explains why we did

not employ these data.

Compromise Estimate

623

Baden.28 The ratio of the two is the employmentstructurefactor S. S is

multiplied by the employment share factor and the absolute capital

stock of Baden to derive the total capital stock for the Reich. More formally,the employmentsharefactoris calculatedas E = LReich / LBaden,

the employmentstructurefactoras

S =[

urrentGemany

(eich

/

LReich

)

/

u[iurrGeermany(LBadenLBaden)

where K is the capital stock, L is the numberof employed, the index i

represents the industrial subsectors. The capital stock is thus KReich =

KBaden*E * S. The thus-calculatedcapital stock is transformedinto an

index with the base year value 100 for 1913.29 Because we add information abouttotal industrialemploymentand industrialemploymentstructure,we do not use a constantmultiplier (E * S) as Hoffmanndid.

So far, Hoffmann's and our capital stock estimate depend on the Baden capital tax. However, we can complement the index by a second

capital stock index calculated from company balance sheet data for 44

large joint-stock companies for 1885-1913 based on a sample by Rudi

Rettig.30This sample covers the main industriesand the main industrial

regions. Rettig's data do not include any firms from Baden. The two

samples are thus independentand we calculate a second index based on

Rettig. We thus employ for 1850-1884 the improved Baden series,

thereafteran average of the improved Baden series and the independently calculatedRettig index. The weights given to the samples are one28

The exact figures are for Baden / Germany:3.03 / 2.55 (1846), 3.08 / 2.60 (1861), 2.87 /

2.68 (1875), 3.17 / 2.68 (1882), 3.20 / 2.68 (1895), and 3.05 / 2.70 (1907). For the years between the census years we linearly interpolatedthe coefficients. In Baden, the average relative

capital intensitywas constantor declining during 1846 to 1875, whereas in Germanyit rose during these decades. Thereafter,the average capital intensity remained constantin Germany,but

rose in Baden.

29 The base year capital stock estimation was originally calculated by FerdinandGrining,

Versuch,pp. 14-18, and subsequentlyused by GerhardGehrig, Zeitreihe, pp. 13-15. Because

Schremmerpresented data only up to 1912, we assumed Hoffmann's 1913/12 annual capital

stock growth rate to be correct.In addition,by multiplyingthe Baden capital stock with the employment share and employment structurefactor, we end up with a capital stock estimation(in

1913 prices) about 35 percent lower than Hoffmann's estimationfor 1913. Such a difference is

possible because Schremmer,Die Badische Gewerbesteuerextensively describesthe systematic

undervaluationof the Baden capital stock. This undervaluationwas partof industrialpolicy, because it lowered the tax base for companies in Baden and thus fostered industrialdevelopment

in the GrandDuchy of Baden.

30

Rettig, Investitions-und Finanzierungsverhalten.

624

Burhop and Wolff

4.2

4.0

-

Corrected Series

Hoffmann's Series

3.8

3.6 3.4

3.2

3.0

. 2.8

02.6 2

1-4

2.4

2.2

....

2.0

1.8

-6,

1.6

,

.

1850 1855 1860 1865 1870 1875 1880 1885 1890 1895 1900 1905 1910

4

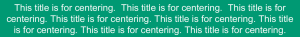

FIGURE

INDUSTRIALCAPITALSTOCKIN GERMANY, 1850-1913, LOG OF BILLIONMARKS,

1913 PRICES

Notes: Investmentis calculatedas the change in the capital stock, it is thus net investment.Like

the industrialproductionseries, the recalculatedindustrialcapital stock series is higher for 1850

thanHoffmann's estimation:5.8 billion marks(in 1913 prices) versus 4.8 billion marks.

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 240; and authors'own calculations.

third for Baden and two-thirdsfor Rettig respectively and are based on

average capital stock during 1885-1912.31

Finally, we multiplied our index value with Hoffmann's 1913 capital

stock estimation.Figures 4 and 5 show our correctedcapital stock and

net investmentseries; the data are in Appendix Table 3.

The investmentdata are presentedin Figure 5.32 A comparisonof the

original Hoffmann and our industrial investment reveals some

difference in cyclical behavior. A shift in investment behavior can be

noticed during the 1870s and late 1880s. Although Hoffmann had an

31Rettig's and Baden's data

jointly cover nearly 10 percent of the German industrialcapital

stock, thus our sample is significantlylargerthan Hoffmann's for the 1885-1913 period.

32Gehrig, Zeitreihe,

connected Grtining's (Versuch) estimate for the capital stock in 1913

with Wagenffihr's(Zur Entwicklung)volume index of investment. The result is a gross investment series for the total economy, a series not comparableto net investment series. Grabas,

Konjunktur,p. 452, presents an investment series only from 1906-1913, based on IPOs and

capital increases of joint stock companies. We do not furtherconsider this series for two reasons: The series is short and the link between capital issues and investment in the entire economy is not self-evident.

Compromise Estimate

625

5,000

4,500

4

4,000

3,500

3,000

-

-

A

Hoffmann'smanufacturinginvestment

Hoffmann'snon-manufacturinginvestment

....3,500 Correctedmanufacturinginvestment

I\

"\

" "*

"

I

""

2,000

0

1,500

500

-500

"

1 185

I

,,,

I

1

11

1',

"

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE5

MANUFACTURINGAND NONMANUFACTURINGINVESTMENT:HOFFMANN'SAND

NEW ESTIMATE,MILLIONMARKS, 1913 PRICES

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 240; and authors'owncalculations.

investmentpeak in 1871, the improveddata only exhibit a peak in 1873,

but with a high level of investmentuntil 1876. Similarly, in the 1880s

Hoffmann's data show a sustained high investment from 1886-1890,

whereas our data have two small downturnsin this period. Finally, after

about 1900 Hoffmann'speaks lead oursby one to two years.

As a robustnesscheck we comparethe two industrialinvestment estimates with nonindustrialinvestment. Hoffmann also presents independently estimated figures for non-industrial-sectorinvestment.33According to his estimation,nonindustrialnet investment startsto grow in

1872, a process lasting until 1876, and followed by a decline until 1880.

This record of the non-industrialsector investmentroughly mirrorsthe

development of our new series. Turningto the early twentieth century,

Figure 5 shows a shift of peaks and troughs. However, the revised

Baden data and Rettig's data, which were employed to constructour industrial investment index, closely co-move and both show the same

cyclical pattern.34We include the new industrialnet investment series

into our revised EH expenditureseries (Figure 6).

33Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 827.

34 After 1885 our cyclical pattern is based on two independentdata series, the Baden-taxseries and Rettig's data.

626

Burhopand Wolff

4.0

3.8

""

EH Hoffmann

EH corrected

p

3.6

3.4

a 3.2

S3.0

2.8

2.6

2.4

1896 19 1 90 1 1

2.2 -- 1856 16

1 --1

11-....

...

1896 1901 1906 1911

1891

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886

FIGURE6

COMPARISONOF THE ORIGINALAND THE CORRECTEDEXPENDITURESIDE NNP,

LOG OF BILLIONMARKS, 1913 PRICES

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 825; and authors'own calculations.

A furtherimportanttopic relatedto the EH series is the calculationof

the implicit deflator.Hoffmannpresentsthe expenditureseries in nominal terms as an NNP and in real terms as an NDP (Net Domestic Product).35From the nominal series we subtractedthe nominal currentaccount balance to get the nominal NDP. The ratio of nominal to the real

NDP then gives the implicit NDP deflator. We comparedthis deflator

with the consumer price index (CPI) of the Imperial Statistical Office,

which is available for the period 1881-1913 and with two wholesale

price indices presentedby Alfred Jacobs and Hans Richter.36 The official CPI exhibits little difference to the implicit NDP deflator for the

availableperiod, whereas Jacobs and Richterdepicts a differing cyclical

behavior.37Thus in this period the implicit NDP deflator appearsto be

superiorto Jacobs and Richter's estimate. In addition,Jacobs-Richteris

a wholesale price index for industrial and agricultural goods only,

whereas the implicit deflator derived from Hoffmann's data is an NDP

35Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 825.

36Hohls, Sectoral Structure;and Jacobs and

Richter,Grof3handelspreise.

37Jacobs and Richter,Grojfhandelspreise.

CompromiseEstimate

627

deflator. In earlier years (before 1878), the Jacobs-Richterindex has a

significantly higher level than Hoffmann's data and converges to Hoffmann's level during 1874-1878. This difference can be explained: As

pointed out, the Jacobs-Richterindex is a wholesale price index of agriculturaland industrialgoods. In the 1870s, however, the relative prices

of industrialgoods comparedto nonindustrialgoods decreased. Therefore the Jacobs-Richterindex overestimates the general price level in

the period precedingthe 1880s because industrialgoods were relatively

more expensive. We decided to deflate our series and most of our subseries with the implicit NDP deflatorused by Hoffmann.38

The third national accounting approachuses factor income. National

income is calculatedby adding up labor and capital income in the economy.39 There are two independent estimates available, one by Hoffmann, and a second by Hoffmann and MUiller.Both series lead to an

NNP at factorcosts in currentprices.40

Hoffmann estimated the national income by using employment census data, multipliedwith the average annualincome of employees in the

respective subsectorsof the economy.41This productgives the labor income of the economy. Capital income is calculatedby applying a constant rate of returnon the economy-wide capital stock. As already discussed, Hoffmann's capital stock estimation for the industrialsector is

too low. In addition, he assumes a constant profit rate on this capital

stock of 6.68 percent, a ratherlow value as Fremdlingpoints out.42 We

use here our correctedcapital stock series and apply a newly estimated

rate-of-returnto this capital stock.

Because comprehensivedata on company profitabilityare not available, we decided to use dividend yields of joint-stock companies as a

proxy. Dividends should be high in times of high companyprofitability

and low in times of bad performanceand are probably a good proxy.

However, for the early years it might be problematic,because the German joint-stock companies law was liberalizedin 1870, and before that

date, the number of joint-stock companies was rather low. Further,

joint-stock companies are mainly large corporations.Small and medium

size companies are thus not covered by the sample. Two types of information are needed for our calculation:first, a time series on the average

dividendyield at the Germanstock market;second, data on the relation38Only the capital stock subseriesis deflatedby a differentprice index.

39Rent income andprofits are included in capital income.

40Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 505; and Hoffmannand Milller, Volkseinkommen,

p. 39.

41 Hoffmann, Wachstum, p. 505.

42Fremdling,National Accounts (1995), p. 88. The rate of returnfor the othernonagricultural

sector is constantat 4.788 percent.

628

Burhopand Wolff

ship of companyprofits to dividends. Time series evidence for the dividend yields is available for the years 1870 to 1913.43 For the period

1851 to 1869 we estimatedthe dividendyield from a sample of 11 jointstock companies in 1851; 31 in 1856, 99 in 1862; by 1869 our sample

covers 166 companies.44Our data are thus quite reliable for the 1860s.

The profit-dividendrelation is calculated using a cross-section of 375

joint-stock companies for the year 1880.45 We assume the profitdividend ratio to be constantat 1.189 for the years 1851 to 1913.46 We

estimate the average return on capital to be 9.63 percent during the

years 1851-1913, but the new series, which can be seen in Figure 7,

fluctuatedaroundthis mean.47

We checked the quality of our profit-rateestimation with the independentdata set by EduardWagon.48 Figure 7 also presentsthis alternative, estimated rate of return.Wagon's and our estimate based on the

data by Richardvan der Borght and Otto Donner have similar properties, we thereforebelieve that our estimate accuratelydepicts the return

on capital in the investigatedperiod.

Because we calculate NNP and not NDP, the income series IH includes foreign income.49 Foreign income consists of capital and labor

income. Hoffmannassumes that there was no net foreign labor income.

He thus looked only at capital income. In addition,he assumed a net total investment of 20 billion marks for 1913, and he assumed zero investment for 1871 and the years before. We do not change Hoffmann's

43Donner,Kursbildung,p. 98.

44 Van der Borght,StatistischeStudien,p. 222.

45 Van der Borght,StatistischeStudien,p. 290.

46 We checked the assumptionof a constantprofit-dividendrelationwith data from 50 industrial firms and nine banks covering the years 1880-1913 taken from Rettig, Investitions- und

Finanzierungsverhalten;and Burhop, Executive Remuneration.In this period the ratio was

nearly constant.

47 There could be a bias in this estimate if the "surviving"companies receive a larger return

on capitalthan a sample of all companies. Tilly, Public Policy, calculatedan approximatesurvivor bias of joint stock companies. He showed that during 1871-1883 the stock marketreturnof

489 companieswas 2.6 percent,whereas the stock marketreturnof the 294 survivingcompanies

was 4.4 percent.Adjusting our returnby this percentagedifference, however, has very little influence on national income. Tilly's data are furthermorenot really comparableto our return

data, because we have returnon capital, whereas Tilly calculates stock marketreturn.In addition, the period 1871-1883 was markedby significant stock marketfluctuations.Furthermoreit

can be assumed that the survivorbias is procyclical, thereby our data should underestimatethe

cycle.

48Wagon, Finanzielle Entwicklung,pp. 175-212. This data set informs us about capital and

profits of a large sample ofjoint-stock companiesfor the years 1870 to 1900. The sample covers

93 companies in 1870, 430 in 1880, and finally 830 in 1900. The two estimationsare quite similar, with a correlationof 0.8. The only majordifference occurs duringthe stock-marketboom of

1872/73, but even this difference of around 11 percent leads to an NNP estimationerrorof less

than 1.5 percent.We thereforethinkthat our profitabilityestimationis quite reliable.

49Hoffmann, Wachstum,pp. 261 and 510.

CompromiseEstimate

18

-1van

- - -

16

629

der Borght-Donner

Wagon

14

12

•

10-

6

4

,

.

2

1851

1856

1861

1866

1871

1876

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE7

RETURN ON INDUSTRIALCAPITALIN PERCENTAGES,1851-1913

Sources: van der Borght, Statistische Studien, p. 222; Donner, Kursbildung,p. 98; Wagon,

Finanzielle Entwicklung,p. 175; and authors'own calculations.

foreign asset series, but do change his rate of return. He assumed a

3 percent rate of returnfor 1913, and he calculated this rate backward

by using a seven-year moving average of Germanlong-termbonds. Instead, we are using the rate describedabove (Figure 7) of returnfor the

Germaninland capital stock and data on the returnat the Germanbond

market.50 The portfolio-mix (bonds vs. shares) is given by Hoffmann.

Figures 8 and 9 present the applied rate of returnand the net foreign

income.

Figures 8 and 9 show an upwardcorrectionof the internationalrate of

returnand thereforealso of Hoffmann's total foreign income data. His

rate of returnin the earlier decades appearsto be implausibly low. In

addition,because our interestrate is not smoothed,the cyclical behavior

of internationalincome is better capturedby our series. Our interestrate

estimation representsa lower bound, because we assume the same interest rate for national and foreign investments.Thus, no risk premium

is containedin our series. Karl ChristianSchaefer shows a higher return

50

Donner,Kursbildung,p. 98.

630

6

Burhop and Wolff

6a-a -

Hoffmann's Series

-

Corrected Series

5

4

b3

2-

.

1871 1874 1877 1880 1883 1886 1889 1892 1895 1898 1901 1904 1907 1910 1913

FIGURE 8

RETURN ON NET FOREIGNCAPITALIN PERCENTAGES,1870-1913

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,pp. 261, 510; Donner, Kursbildung,p. 98; and authors' own

calculations.

for international investments than for national investment for some

countries.5"However, representativefigures on investment abroad are

not available. See Figure 10 for our correctionto the IH series.

Hoffmannand Miiller present a second income estimate,NNP at factor costs, based on the official income calculation of the Kaiserliche

StatistischeAmt, which published such a series from 1891 onward, See

Figure 11.52 Hoffmann and Miiller extend the official series back to

1851 by using archival material from several tax offices, startingwith

Prussia in 1851.53 Data for other states become available from 1871,

and for 1913 over 90 percent of population is covered by these data.54

We label this series "IHM."

Schaefer,Deutsche Portfolioinvestitionen.

Hoffmannand Mtiller, Volkseinkommen,

p. 39.

53 We linearly interpolatedthis income series for the missing values in 1867, 1868, and 1870.

54 From 1851 to the mid 1860s, Prussiandata cover around48 percentof the Germanpopulation. After the "unificationwars"(1864-1866), this figure rose to 60 percent.Prussiawas a very

heterogeneous state (agriculturein the east, industryin the west) and later studies showed that

the Prussianincome developmentwas representativefor Germany.For 1874, data from Prussia,

Saxony, Hesse, Hamburg,and Bremen are available and 70 percentof the Germanpopulationis

covered.

51

52

CompromiseEstimate

631

7

5I3

0

M M-M

Foreign income, Hoffmann

Foreign income, corrected

I

1871

1875

1879

1883

1887

1891

1895

1899

1903

1871

1875

1879

1883

1887

1891

1895

1899

1903

1907I

I I

I

1907

I

I

I

11

1911

FIGURE

9

NET FOREIGNINCOME,IN LOG OF MILLIONMARKS, 1870-1913 (1913 PRICES)

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,pp. 261 and 510; and authors'own calculations.

Four shortcomings of tax office data are raised by Ritschl and

Spoerer.55The taxation base is only large enough to compute precise

estimates after the Prussian tax reform of the early 1890s and similar

reforms in other states. A second problem is the fact that tax payers

declared only a part of their income.56Hoffmann and MUillercorrected

for this bias using results of a 1913 Reichstag commission.57 Third,

there was a tax-free minimumincome, which is not covered in the data.

Hoffmann and MUilleraddress this issue by taking an estimate of the

average income below the tax-thresholdin 1913. They extrapolatedthis

numberbackwardsusing a wage index. The total tax free income was

then calculatedby multiplying the numberof employed people less the

Ritschl and Spoerer,Bruttosozialprodukt,p. 30.

Hoffmannand Muiller,Volkseinkommen.

After the introductionof the new Prussianincome

taxation code in 1891 this problem became apparent.Hettlage, Finanzverwaltung,briefly describes the Germantaxation system. The highest tax rate on income in Prussiawas 3 percent,

incentives to evade taxes were thus ratherlow. Yet, one should note that the state income tax

was supplementedby local income taxes and thus the tax rate could be as high as about 9-10

percentin some Prussiancities.

57 This bias appearsto create a level ratherthan a cyclical difference.

55

56

632

Burhopand Wolff

4.5

.- - -

4.0

_

Hoffmann's Series

CorrectedSeries

3.5

. 3.0

2.5

1851 1855 1859 1863 1867 1871 1875 1879 1883 1887 1891 1895 1899 1903 1907 1911

FIGURE

10

COMPARISONOF THE ORIGINALAND THE CORRECTEDINCOME-SIDENNP

SERIES(IH), IN LOG OF BILLIONMARKS, 1913-PRICES

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 505; and authors'own calculations.

number of tax payers with the average below threshold income.58

Fourth, before the reform of 1891, two types of income were

distinguished in Prussia: fixed ("fundiert")and variable ("unfundiert")

income. Fixed incomes were taxable in the year of payment,whereas in

the case of variable incomes, taxes had to be paid one year after the

income flow. Sometimes these incomes were averaged over the last

three years. This means for business cycle analysis that the cycle could

be shifted and dampened. Because large parts of the population are

covered by the taxation base approach,the data are relatively reliable

even before the 1890s.

Both income series, IH and IHM; and the output series OH yield an

NNP at factor costs, not an NNP at marketprices like EH. We thus add

taxes on productionand imports (indirect taxes) to get NNP at market

prices.59 Spoerercalculated the indirecttaxes for 1901 to 1913, and he

roughly guessed that the growthrates of indirecttaxes for Germanywas

58The income distributionis stable over time. In Saxony-other data are not available-the

lowest quartileof the populationearned8.2 per cent of the total income in 1874, and 7.2 percent

in 1913 as calculatedfrom Jeck, Wachstum.The bias from this source seems quite small.

59 We left out any correctionsfor subsidies because in 1913 they amountedto only 30 million

marks,whereas the indirecttaxes were around2,867 million marks.

CompromiseEstimate

633

4.00

- - -

CorrectedSeries

Hoffmann'sSeries

3.75

7

3.50

3.25

3.00-7

Of

2.75 •I

2.50

--

1 11

I

I

I

I I

7

I--TT-,

.

.

, .. ..-I

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE11

COMPARISONOF THE ORIGINALAND THE CORRECTEDINCOME-SIDENNP

ESTIMATE(IHM), IN LOG OF BILLIONMARKS, 1913 PRICES

Sources:Hoffmannand Mtiller, Volkseinkommen,

p. 39; and authors'own calculations.

around7 percent from 1850 to 1880, and circa 1 percent from 1880 to

1900.60 We used a mean value of 4 percent. Startingwith Spoerer's figure for 1901, we calculated the amount of indirect taxes backwardto

1851 by using this growthrate guess.61

The resulting four estimates of German NNP at market prices are

presented in Figure 12. The data are in Appendix Table 2. To summarize our main corrections:We add new net investment data to the expenditureseries (EH), new industrialproductionfigures and foreign income to the output series (OH), capital income and foreign income

corrections to the income series (IH). In addition, indirect taxes were

added to OH, IH, and IHM. Therefore, we have four NNP series at

market prices. National accounting requires them to be equal, differences in the series are thus a result of imprecise estimations.There are

importantlevel differences in the new series. Especially in the 1850s

60

Spoerer,Taxes, 178.

61We deflated thep.indirect taxes with the Hoffmann

implicit NDP deflator discussed above.

There is no generally acceptedway of deflatingtax revenues,however, these taxes are levied on

a wide range of productsand thus using an NDP deflatorseems appropriate.

Burhopand Wolff

634

4.1

.

.

EHcorrected

- - - - OH corrected

3.9

-----I

3.7

H corrected

-------IHM

corrected

3.5

3.

S3.1

2.9

2.7

2.5

2.3 2.

1

-

-

,7

1

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

12

FIGURE

COMPARISONOF THE FOUR CORRECTEDESTIMATESOF REAL GERMANNNP, IN

LOG OF BILLIONMARKS, 1913 PRICES

Source:Authors' own calculations.

and 1860s the IHM series is considerablyhigher, also it has more pronounced cyclical movements. In 1892 the four series almost converge

and the differencesbetween the series stay relatively small.

Table 1 presentssummarystatisticsof the four revised and of the four

original series. The coefficient of variationof the four series varies. The

IHM series has the lowest coefficient of variation and also the lowest

standarddeviation, it is thus the smoothest series with the fewest fluctuations. The IH series on the other hand has the largest coefficient of

variation.The EH and OH series are in between, they also differ somewhat.

Since the work of CharlesR. Nelson and CharlesI. Plosser it has become standardto test macroeconomic time series for the existence of

stochastic trends (unit roots).62 This has fundamentalimplications for

the analysis of business cycles, because in the case of a unit root all innovations to the series have permanenteffects, while in the case of a deterministictrend,innovationswill only have temporaryeffects. We em62Nelson and

Plosser, Random Walks.

CompromiseEstimate

635

TABLE1

DESCRIPTIVESTATISTICSOF THE SERIES

1851

1913

Coeff. of

Variation Growth

ADF Test

KPSS Test

Breitung

Test

EH revised

EH

OH revised

OH

IH revised

IH

IHM revised

IHM

do not reject do not reject

46.9

2.58

10,379 51,540

reject

do not reject

2.6

47.8

reject

10,379 52,440

reject

2.47

do not reject

do not reject

46.0

11,890 55,252

reject

do not reject

2.64

do not reject

48.6

9,390 48,480

reject

do not reject

54.1

2.93

9,019 55,578

reject

reject

do not reject

do not reject

51.6

2.79

8,803 49,696

reject

do not reject

41.8

1.99 do not reject

15,370 53,271

reject

do not reject

1.94 do not reject

40.8

15,011 50,404

reject

Notes: Coefficient of variationis standarddeviationdivided by mean. Growthrefers to annual

average growthrates over the period 1851-1913. ADF test with Ho:series has a unit root with

drift;KPSS test with Ho series is trendstationary.Breitung's test has Ho of unit root with drift,

while H1 is trendstationary.

ployed the augmentedADF test, which has the null hypothesis (Ho) of

unit root. We were able to rejectHo for the series EH and for the revised

IH. However, the ADF test has low power to reject comparedto near

unit root alternatives.63We therefore also employed the KPSS test,

which tests the Ho for trend stationarity.64In all cases we were able to

reject trend stationarityexcept for the EH series. As a furtherunit root

test, we employed the test developed by JOrgBreitung.65Breitung's

variance ratio statistics is similar to the test statistics suggested by

KPSS, but it assumes nonstationarityunderthe null hypothesis. The results of the Breitung test are in line with the results of the KPSS test.

We thereforeconclude that the IHM, IH, and OH series, both the original, as well as the revised, exhibit a unit root. The EH series, on the

otherhand, is trendstationary.66

COMPROMISE

ESTIMATEOFGERMANNNP

National accountingrequiresthe four estimates of GermanNNP to be

equal. This identityrequirementis a naturaltest for our correctedseries.

As Figure 12 shows the four series are not equal. A pragmaticsolution

could be to averagethe four improvedseries.

63See, for

example, Rudebusch,Uncertain UnitRoot.

64The optimal truncation

lag length was calculatedaccordingto an automaticbandwidthselection routine as presented in Hobijn et al., Generalizations.The routine is implemented in

STATA. The optimaltruncationlag was five for all series.

65Breitung,NonparametricTests

66The unit root tests were conducted on the log-transformedseries. We performedthe unit

root tests in additionon the original series. In this case, all four series have a unit root.

Burhopand Wolff

636

Assumethat all four estimatesdeviateby an error sj fromthe true

developmentof GermanNNP, thus Y,= Y*+ e where Y* is the true

GermanNNP, and Y1representsthe estimate.To calculatebalancedestimatesof NNP, whichcome closestto the trueseries,we follow Solomou andMartinWeale,who calculatebalancedestimatesof U.K. GDP

from1870-1913.67As for the Germandata,the startingpointis the observationthatdifferentestimatesof GDPfromoutput,expenditure,and

income sides yield differences in the series, even though they should be

equivalent. The aim is now to find an estimate, which comes closest to

the true GDP. Supposewe know the variance,vi, of the error,Ee,of

each of the independentestimates.Thena least-squaresis given as the

solution,Y,*,whichminimizes68

it t

Ui

t

) 2t t3t

V2

U3

If the threeestimatesareindependent

andequallyreliable,thena simple

estimate.In the case of

arithmeticaverageof the seriesis a least-squares

the UnitedKingdom,SolomouandWealeuse informationprovidedby

Feinsteinto allocatedifferentdegreesof reliabilityto eachof the series

andtherebyderivea balancedestimateof U.K. GDP.69Hoffmannand

Hoffmannand Miller, however,do not providemuch informationon

the differentdegreesof reliabilityof theirestimates.

Thequalityof the outputseriesseemsgoodbecausemanyproduction

figureswere surveyedduringthe nineteenthcentury.In addition,we increasedthe numberof datapointsfor the OH series,therebyimproving

its cyclicalproperties.On the otherhand,productionfiguresfor the tertiarysectorarebarelyincluded.We amelioratedthe qualityof EH significantlyby includingnew investmentdata.However,becauseprivate

consumptionis estimatedvia a residualconcept,measurementerrors

to the EH series.The qualfromthe OH seriesarepartiallytransmitted

the

of

third

national

the

accountingseries, IH series,was quintessenity

on the

tiallyimprovedas we includeda variablereturn-on-investment

67Solomou and

Weale, Balanced Estimates.

68

Solomou and Weale, Balanced Estimates; and Feinstein, National Income. The least-

squaresapproachdatesbackto Stoneet al., Precision.It was takenup againby Weale,Testing

LinearHypotheses.

69

The balanced and compromise estimates are shown to be significantly different. Greasley

and Oxley (Balanced Versus CompromisedEstimate) take up the issue and compare the time

series properties of the estimates. One main difference between the two estimates is the fact

that the balanced estimate is difference stationary,whereas the compromise estimate is trend

stationary.

CompromiseEstimate

7.0%

7.0%-Using

-

IHM original

-

-"

Using EH original

6.5%

6.0%

5.5%

637

.

A

,

I

5.0% -

00

?

4.5%

4.0%

3.5%

186

3.0%

8F-T1F

1881T18861811896T-91I90-I 1T

9Ti

~~,8661871-yT76

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE13

THE EVOLUTIONOF CIVIL GOVERNMENTEXPENDITUREAS A PERCENTAGE

OF NNP

Sources: Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 724; and authors'own calculations.

industrialcapital stock and new capital stock data. In the same way, we

enhancedforeign income data.

The two major advantages of IHM are its independence of Hoffmann's three estimates of NNP and its large data base, as the overwhelming part of the Germanpopulation is covered by IHM. On the

other hand it shows a significantly higher level for the early decades.

We checked the plausibility of this higher level of IHM by calculating

government shares of NNP. In fact, one can plausibly assume that the

shareof civil governmentexpenditurein NNP should not be falling during a prolonged period of economic growth.70 Figure 13 compares the

civil governmentexpenditureshare over EH with the same over IHM.71

The respective share is decreasingusing EH until 1869, a finding which

is unlikely, especially in view of rising employment. The share of civil

governmentemployees in total employmentwas increasing in the same

70 The

public finance literaturelabeled the growth of the government expenditureshare in

GDP over time "Wagner'slaw."

71Civil expenditureis taken from Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 724. The evolution of the share

with IH and OH is similarto the one with EH.

638

Burhop and Wolff

4.0 3.8

3.6-

S3.4

3.2.

5 3.0 2.82.6

2.4

1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE14

EVOLUTIONOF COMPROMISEESTIMATEOF GERMANNNP, IN LOG OF BILLION

MARKS, 1913 PRICES

Source:Authors' own calculations.

period from 1.03 percentin 1849 to 1.21 percentin 1867.72 The shareof

personnel expenditure to total expenditure was constant. A falling

government expenditure share combined with a rising employment

share would imply a decrease in the relative wage of public sector employees over nearly two decades, a very unlikely finding. On the other

hand, the governmentexpendituresharefor the IHM series was roughly

constant, which is a sign of the better quality of the level estimate for

IHM.

To sum up, all series have advantagesand disadvantages,and to assign relative degrees of reliabilityis difficult. We thereforesuppose that

the three series of Hoffmann are equally reliable and form a balanced

estimate of them as a simple arithmeticaverage of the three series. Because IHM is an independentestimate we assign a weight of 50 percent

to it for calculatingour final compromiseestimate.

The resulting compromise estimate is presented in Figure 14. The

compromise series obviously has an average coefficient of variation.

72

Hoffmann, Wachstum,p. 203.

CompromiseEstimate

639

TABLE

2

DESCRIPTIVESTATISTICSOF THE COMPROMISEAND OLD COMPROMISESERIES

1851

1913

Compromise 12,900 53,700

EH

10,379 52,440

Notes: See Table 1.

Coeff. of

Variation Growth ADF Test

47.00

47.80

2.33

2.60

KPSS Test

Breitung

Test

do not reject

do not reject

reject

do not reject

reject

reject

The average annual real growth rate of the best estimate of German

NNP is 2.3 percentduring 1851-1913. Just as in three of the four single

series, the compromiseestimatehas a unit root.

Table 2 presents the properties of the compromise series and compares it with the original EH series by Hoffmann, which is the most

widely used series for Germannational accounting.73The compromise

series has a higher level of economic activity in 1851 and also in 1913.

Its growth rate is lower and the coefficient of variationof the compromise series is slightly lower. Turningto per capita values, the compromise series leads to an estimate of 362 marks in 1851, whereas the

original EH series was 291 marks. This difference diminishes in the

course of the period and both estimates end up with roughly 800 marks

per capita, which representsan average annual real per capita growth

for the compromiseseries of 1.3 percent and 1.6 percent for the EH series. Remarkableare the differences in unit root properties:The compromise clearly has a unit root, as all three tests confirm.In contrast,the

old EH series is trendstationary.

TRENDSIN GERMANNNP

FLUCTUATIONS

AND LONG-TERM

Long-TermTrends,1851-1913

The average yearly growth rate of the compromiseis 2.3 percent.As

mentioned previously, this growth rate is lower than that of the often

employed EH series. The growth rate difference of 0.3 percent annually

reduces the 20-percentinitial level differenceto nearly zero.

A graphicalanalysis of the log-transformedcompromisedoes not reveal a break in the trendgrowth rate. A growth accountingexercise can

be performedon this long-term growth rate and might yield additional

insights because the new series not only exhibits lower growthrates,but

73See, for example, Maddison, World Economy; and Mitchell, International Historical

Statistics.

640

Burhop and Wolff

TABLE

3

GROWTHACCOUNTING:AVERAGE CONTRIBUTIONTO GROWTH,1851-1913

(percentages)

Contributionto NNP Growth

EH

Compromise

Industry

Source:Authors' own calculations.

Labor

Capital

TFP

27.7

25.4

44.2

11.8

10.7

30.5

60.5

63.9

25.9

also includes a higher capital stock series.74 Startingfrom a linear homogenous productionfunction (for example, a Cobb-Douglastype) and

factor remunerationat marginal product, growth of output can be decomposed into the contributionof growth of capital, labor, and a remaining term, the Solow residual, which is interpretedas a measure of

the contribution of technological progress. Employment and capital

growth must be weighted by the respective income shares of the factor.

We took the average income shareof capital for the entireperiod, which

is 0.244 for the Hoffmann's data and 0.241 for the revised data.

Table 3 shows that the relative importanceof the three factors labor,

capital, and technology is alteredby our data modifications:Labor and

capital accumulationcontributeless to growth than before; total factor

productivity(TFP) gains importance.Because TFP is calculatedas a residual, a smallerpartof growthcan be explainedwith the new data.75

Figure 15 shows the evolution of TFP over time, normalizedto 1851

equals one. Both decompositions for the NNP give a tremendous increase in TFP of 158 percentwith the old data and 182 percentwith the

revised data. The TFP level of the revised data is similar or largerthan

for the unreviseddata for the entireperiod.

This residual TFP growth is unexplainedby growth accounting. According to Broadberry,structuralchange within the German economy

could be a reason for increasedTFP growth.76Factorswere reallocated

from low-productivity agricultureto high-productivitymanufacturing,

which increased the aggregate productivity level of the economy. In

fact, Figure 15 shows that TFP growth in the industrysector was much

74Note that our economy-wide capital stock series includes the value of land. Hoffmanndid

not include it in his economy-wide capital stock. On page 234, Hoffmannpresents the value of

land in currentprices and on page 569 the land price index. Dividing the two indices gives a

constant value of land in 1913 prices of 73 billion. This implies that TFP growth is high, because a large partof the capital stock is fixed.

75 Schremmer (Wie gross war der 'technische Fortschritt') did a similar exercise with

Hoffmann's original IH series. He calculated a TFP share of 43 percent, a value close to our

calculationwith the EH series if we do not include land. Schremmerneglected the role of land

as capital in production.

76

Broadberry,ProductivityRace.

641

Compromise Estimate

2.4

-

Economy-wide,Hoffmann'sdata

correcteddata

2.2Economy-wide,

Industrialsector, correcteddata

2.0

A

1.8 -*

1.61.4-

1.2

1.0

0.81851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911

FIGURE15

DEVELOPMENTOF TOTALFACTORPRODUCTIVITY,1851-1913

Source: Authors' own calculations.

lower than for the entire economy, growing only by 57 percent. Performing standardgrowth decompositionfor the industrysector it can be

seen that growth of this sector was mainly drivenby additionallabor input. One reason for this additionallabor input is the labor productivity

difference between industry and the other sectors as can be seen in

Table 4. Over the entireperiod the laborproductivitywas always higher

in the industrialsector for the correctedseries. Workersthereforehad an

incentive to move to the industrialsector.77

Because we have productionindices for each industry and employment data for each industry,we can decompose the growth of output

into two components: A productivity component and the increase in

employment. We calculated the average increase in the productionindex for each industryas the geometric mean of the yearly growth rates

for the availableyears. Similarly,we computedthe averagegrowthrates

of employment in each industry.Subtractingemployment growth from

77 In the original series, until 1907 labor productivitywas lower in the industrialsector, an

unlikely finding.

642

Burhopand Wolff

TABLE 4

LABOR PRODUCTIVITYOF THE ORIGINALAND CORRECTEDDATA: ENTIRE

ECONOMYAND INDUSTRIALSECTORIN 1913 MARKS

1851

Compromise

Total economy

863

Industry

1,161

Original

Total economy

694

553

Industry

Sources:Authors' own calculations.

1880

1913

1,057

1,456

1,732

2,232

1,047

979

1,692

1,899

production growth yields average increases in labor productivity for

each industry for the investigated period. These labor productivityincreases reflect two components that we cannot furtherdecompose: increases in the capital stock per workerand increases in efficiency of the

work process.

The average industrialoutputgrowth rate in the investigatedperiod is

2.85 percentper annum(see Table 5).

Output, employment, and productivity grew in all industries. Employment growth in the investigated period was 1.77 percent per year.

Outputand also employmentgrowthwas highest in the gas, water, electricity, paper production,metal production,and the chemical industry.

Productivity increases were similarly very high in these sectors. For

1851 the employment shares were highest in clothing, textile, food and

wood production.The shares of textile and clothing, however, dropped

significantly over the period by 10 percentage points. On the other

hand, the metal processing industryand constructionindustryhad significantly higher employmentsharesin 1913 than in 1851.

In a second step we can deriveaggregatelaborproductivityincreasesby

weightingthe sectorswith their 1851 employmentsharerespectiveto their

1913 employmentshare.Aggregateannualproductivitygrowthwas 1.725

percentgiven the employmentsharesof 1851, and 1.848 percentgiven the

structureof 1913. Thus,the structureof the economychangedsuchthatsectorswith a higherproductivitygrowthincreasedtheiremploymentshare.

The GermanBusiness Cycle, 1854-1910

In this section, we present and discuss the business cycle ramifications of the compromiseestimate of GermanNNP for the years 1854 to

1910.78 To obtain a business cycle, we need to decompose the univar78 Due to the filteringtechnique,we

are losing the first and final threeyears

CompromiseEstimate

643

TABLE

5

DECOMPOSITIONOF PRODUCTIONIN THE AVAILABLE INDUSTRIALSECTORS:

OUTPUT, EMPLOYMENT,AND PRODUCTIVITYGROWTH,EMPLOYMENTSHARES

IN 1851 AND 1913

Sector

Output

Employment

Productivity

Stone and soil production

Metal producingindustry

Mwtal processing industry

Chemicalindustry

Textile

Leatherproduction

Clothing industry

Wood

Paper

Food

Gas, water, electricity

Construction

All sectors

4.15

6.90

6.00

6.23

2.78

2.48

2.46

3.24

7.36

2.57

10.32

3.14

2.85

2.56

3.58

2.96

3.90

0.50

0.92

0.98

1.48

3.80

1.63

7.64

2.47

1.77

1.59

3.32

3.04

2.32

2.28

1.56

1.49

1.76

3.56

0.94

2.68

0.67

Share

1851

Share

1913

4.47

1.42

8.80

0.77

23.06

0.97

24.05

10.56

0.80

14.89

0.03

10.19

100

7.21

4.24

18.08

2.78

10.55

0.57

14.79

8.85

2.70

13.67

0.92

15.62

100

Sources: Hoffmann Wachstum,pp. 196 (employment) and 390 (output); and authors' own

calculations.

iate time series of GermanNNP into the components of a cycle and a

trend. Numerous statistical techniques have been proposed for that

purpose. Fabio Canova examines the business cycle propertiesof time

series using a variety of detrendingmethods.79 He shows that different

filters extractdifferentinformationfrom the time series. Thus, business

cycles vary considerablywith the choice of differentfilters.80Marianne

Baxter and Robert King develop a band-pass filter, which allows the

isolation of business cycle fluctuationsin macroeconomictime series.81

The approximatefilter extracts a specified range of periodicities, and

otherwise leaves the propertiesof this extractedcomponentunaffected.

The filter does not introducephase-shifts, so the extractedtime series

will also be stationaryif the original series is integratedof the ordertwo

79Canova,Detrending.

80 Burhopand Wolff, Datenwahl and National Accounting,comparethe cyclical propertiesof

four GermanNNP estimates during 1851-1913 with four differenteconometrictechniques.The

four estimates by Hoffman, Wachstum;and Hoffmannand Mtiller, Volkseinkommen,are shown

to have differing cyclical properties, irrespective of the methodology chosen. Furthermore,

Burhopand Wolff find thatbusiness cycles in some periods vary with differentmethodologies.

81Baxter and King, Measuring Business Cycles. Another standardmethod, the HodrickPrescott (HP) filter, has been shown to generate artificial cycles if the series contains a unit

root (Cogley and Nason, Effects). We therefore do not employ the HP filter. The HP cycle,

however, looks very similar to our presented results, if 2 = 100 as a smoothing parameteris

chosen. The precise dates are in some cases shifted by a year for booms and recessions. Thus

employing anothernonstructuralfilter gives very similar results. We opted against employing

a structuralfilter, such as a Kalman filter (for an applicationto historical data see Crafts et al.,

Climacteric).

644

Burhopand Wolff

or less.82 Furthermore,the extractedbusiness cycle is unrelatedto the

length of the sample period. The filter is basically a moving average

with weights chosen in such a way as to approximatethe ideal filter,

which only allows specified periodicities to pass. In their choice of periodicities Baxter and King follow the classical definition of Arthur

Bums and Wesley Mitchell, who specified that business cycles were

cyclical components of no less than six quartersand less than 32 quarters (eight years).83This filter thus has well determinedproperties, is

very suitable for a business cycle analysis, and is employed here to extractthe cycle.

Our main points of interest are booms and recessions.84We define a

boom as a period of actual NNP higher than trendNNP until it reaches

the local maximum, a recession is defined as a period of actual NNP

lower than trendNNP until the local minimum. In this context, "local"

refers to the intervalbetween two crossings of the trendline.85

Figure 16 depicts the percentagedeviation of actual NNP from trend

NNP for the years 1854 to 1910 measuredby the band-passfilter.

The business cycle reveals strong fluctuationsduring the late 1850s

and early 1860s, thereafterthe normalized cycle appearsto be of constant magnitude. Table 6 shows the exact dates of booms and recessions, using our definitions and compares the dating with Knut

Borchardtand Craig and Fisher who both employ the original EH series.86

In total, 11 booms and 12 recessions are reported,with an average

length of a cycle (from peak-to-peak)of aroundfive years. Besides the

dating we also reporta measure of the intensity of a boom or a recession. For the intensity measure, we calculated the total trend deviation

duringa boom or recession period and divide this figure by the average

total trenddeviations of all boom respective recession periods.

The first decade under consideration can be characterizedby very

strong fluctuations: Two of the three strongest recessions and the

strongest boom fall in the period 1855-1862. During the 1860s, many

"noneconomic"factors influenced the Germaneconomic development,

82 It is

thereforeirrelevant,whether we employ the log-transformedseries or the original series. The filteredbusiness cycle was in both cases virtuallyequivalent.

83 Burns and Mitchell, MeasuringBusiness Cycles.

84 We do not investigate in detail questions such as the length of the cycle. For evidence on

this in a historicalcontext, see A'Hearn and Woitek, More InternationalEvidence.