Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems Coupling Agroecology

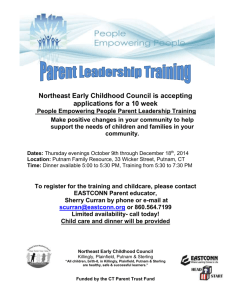

advertisement