GO 221 – Capitalism and its Critics Syllabus

advertisement

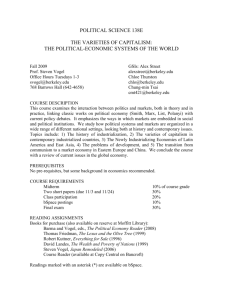

GOVERNMENT 221: CAPITALISM AND ITS CRITICS Monday/Wednesday 1:00-2:15, Diamond 122 Assistant Professor Lindsay Mayka LRMayka@Colby.edu Office Hours: Wednesday/Thursday 2:30-4:00 – Diamond 253, or by appointment Course Description This course examines the interaction between politics and markets, both in theory and in practice, linking classic works on political economy (e.g. Smith, Marx, List, Polanyi) with current policy debates. It emphasizes the ways in which markets are embedded in social and political institutions. We study how political systems and markets are organized in a wide range of different national settings, looking both at history and contemporary issues. The course is divided into six sections, which each look at the social and political institutions behind capitalism. The first section reviews classical theoretical frameworks used to study political economy. In this section, we identify the three major theoretical frameworks: liberalism, Marxism, and mercantilism. The three frameworks differ in their perceptions about the appropriate roles of state and markets in facilitating economic activity. We will discuss the main tenets of each camps, as well as the historical context that gave rise to each of these theories. In the second section, we will examine the analytical frameworks used in different academic disciplines to study market institutions. This section highlights the differing assumptions and methods of analysis used by sociologists, such as Karl Polanyi and Neil Fligstein; economists, such as Douglass North and Oliver Williamson; and political scientists, such as Charles Lindblom. Despite their many differences, scholars from all three camps acknowledge the important role that institutions play in structuring capitalist markets. They may disagree about whether the pursuit of material self-interest is in human nature or how important political power is to study the functioning of markets, but all agree that markets must be constructed through political and social institutions and do not naturally spring into being. The third, fourth, and fifth parts apply these theoretical frameworks to study contemporary challenges for capitalist economies from advanced industrial economies, developing economies, and post-communist economies. For advanced industrial economies, we will examine the different varieties of capitalism that have developed, and will then explore how these capitalist models have responded to the global trend towards deregulation and integration of the past 30 years. Can countries with generous welfare states sustain this model, or should they accept the terms of austerity? Are advanced capitalist economies converging towards an universal model of deregulation and liberalization? And does increased globalization and decreased regulation mean that financial crises, like the one experienced in 2008-2009, are inevitable? 1 During our examination of developing economies, we will ask the question of why some countries have developed while others have not. Do state attempts to guide economic activity lead to economic advancement, or stagnation? What role can and should the government play to foster economic development? Should countries integrate into global markets? And what role can foreign aid play in the development process? Fifth, we will study the diverging fates of countries that have transitioned away from communism. These countries face the difficult challenge of dismantling communist economic institutions while also constructing the myriad political and social institutions needed for capitalism to take root. How can countries overcome the political barriers to economic reforms? Is there a blueprint that countries should follow to construct capitalist markets, or should each country pave their own way? Looking to China and Cuba, we also ask whether economic liberalization necessarily destabilizes authoritarian rule and what will be the fate of the communist parties of these two countries. In the final section, we will examine the changes that have been brought on by globalization and the information revolution. These changes appear to remove geographic barriers, increase the speed of economic activity, and introduce a very different model of capitalist activity than we had during the era of manufacturing and industry. Are states less important in the new globalized world? And how will market institutions change with the new information-based economy? Course Objectives 1. Understand different theoretical frameworks for understanding institutions and institutional analysis. 2. Be able to apply these theoretical frameworks to the study of the political, economic, and social institutions underlying markets. You should also be able to apply these theoretical frameworks to other areas of political science (e.g. new institutionalist economics analysis of elections). 3. Better understand the domestic and global politics behind capitalism, and some of the details of how markets work. This course should make it easier for you to read the newspaper and think critically about current events. 4. More broadly, in this course you will be pushed to strengthen your critical thinking skills, learning to not only identify the causal claims of the authors you read but also to challenge their approaches and assumptions. 5. Improve your writing and critical analysis skills through several paper assignments. Expectations of Students I expect you to make this class a top priority and to treat your colleagues and me with professional respect. You should arrive on time and ready to engage. Students must be fully prepared at all times to discuss the readings and concepts from that day’s material, and that of previous lectures. Please print out the readings and bring a copy to class. Particularly in the first couple weeks, I need you to tackle the readings with enthusiasm. When everyone does that, we will have set an excellent tone for the semester. In addition to readings, every class period will require you to spend some non-reading time preparing for class. Create a habit of setting aside non-reading time to prepare your ideas. 2 Attendance is mandatory, but students are allowed one free absence that won’t count against your grade. However, students may not use this absence on the day of a simulation or a debate. Please show up on time for each class. You can expect me to be tirelessly enthusiastic and to work hard for you, both this semester and in future semesters when you need advising and reference letters. I will hand back work promptly, I will make time for you, and I will provide constructive and encouraging feedback. I encourage all of you to stop by my office hours with a question, or even if you don’t have a question and would just like to chat about the class, what’s going on in the world, or life after Colby. I am available during the scheduled office hours, as well as by appointment in person or by skype. My skype ID is LRMayka. You can reach me best via email at LRMayka@colby.edu. I will respond to you within 24 hours during the week, and within 48 hours on the weekend. Assignments Students will be assessed based on their performance on a takehome midterm exam, two analytical papers, a final exam, four short assignments, and active participation in class. The grade breakdown follows: Takehome midterm exam Analytical paper #1 Analytical paper #2 Final exam Short assignments Class engagement 20% 20% 20% 25% 5% 10% Takehome Midterm Exam In lieu of an in-class midterm exam, students will complete a takehome midterm exam. The midterm exam should be double spaced with 1-inch margins and size 12 Times New Roman font. The midterm will be open note/open book. The exam will be distributed on October 2nd during class and is due October 4th at 5 pm on moodle. Barring a documented emergency, the paper due dates are final and will be marked down a full letter grade for each day late. If you turn it in at 6 pm, that counts as a full day late. Please note that you are responsible for ensuring that you properly upload your final draft onto moodle on time. If you upload a rough draft, that’s the draft I grade. If you have technical difficulties and can’t upload until 5:15, I will count the paper as late. Don’t wait until 4:58 to start uploading. Analytical Papers For Sections III, IV, and V, students will write papers for two sections of their choice. Each paper is worth 20% of your grade. Students also have the option of writing all three papers, in which case I will count the two highest scores towards your final course grade or reweight the 3 grade breakdown to make the papers 50% of your final grade, reducing the midterm to 15% of your grade and the final to 20% of your grade. All papers must be 6-7 pages double-spaced, size 12 Times New Roman font with 1-inch margins. In response to a paper prompt, students will construct an argument by utilizing evidence from two countries: one that is covered in course materials, and another country that has received less attention. For example, in the section on developed economies you might write a comparison of Germany (covered in lectures/readings) and France (covered less in lectures/readings). I encourage you to come in to my office hours to discuss your selection of country cases for these papers, and to confer with library staff on research strategies. The principal objectives of the analytical papers are: 1, to give students with a greater opportunity to engage with the course material than is possible with a time-crunched in-class exam; 2, to provide feedback on writing; 3, to give you an opportunity to explore course themes as they apply to other countries; and 4, to give you some practice conducting research. These are not research papers, per se, but do require you to do some additional research. Analytical papers are due at 5 pm on the day (not the class) after we complete that section (i.e. on Tuesdays and Thursdays). Please submit your papers electronically via moodle. As with the midterm, papers will be considered late if turned in after 5pm and will be marked down a full letter grade for each day late. Final Exam Students will take a written final exam during the officially designated period – no exceptions. The final exam will be cumulative and will consist of essays, short answer questions, and identification of key terms. The final exam is worth 25% of your grade. Short Assignments Students will complete four short assignments, which will be submitted via moodle at 10 am before class. The assignments are designed to help you process the readings in advance of class so we can have a productive discussion. These assignments cannot be turned in late. I will grade these assignments with a check plus (A range), check (B range), or check minus (C range). The assignments are worth a total of 5% of your final grade. Class Engagement Students are expected to attend and to be active participants in all classes. The class engagement grade for this class is not a residual category – simply showing up to without engaging with the material is not sufficient! Your grade will include your overall participation during lectures, your performance during one of two simulations we will undertake this semester, and your performance during one of two class debates. Class engagement will be 10% of your grade. Simulation: We will undertake two simulations this semester: one on the 2008 financial crisis, and one on the future of socialist rule in Cuba. For each simulation, approximately 1/2 of students will be participants while the remaining 1/2 will be observers. Thus, each student will participate in one simulation. Each participant will prepare in advance for her or his role. Observers watch the exercise, possibly playing a small role (e.g., casting ballots or asking 4 questions of the core participants). At the end of the simulation, observers will discuss the final outcome and provide feedback on their classmates’ performance. Debates: We will hold two formal debates in this course: one on the potential of foreign aid to advance development, and one on globalization. For each debate, half of the students will be active debaters, while the other half will be in the audience. Each student will serve as a debater in one of the two debates. I will provide the debate topic and debaters will be divided into two opposing teams. Each team will meet outside of class to plan the details of their argument and coordinate the roles of each team member. The teams will also meet with me to discuss their plan. On the day of the debate, those in the audience will have the opportunity to pose follow up questions to each team and will vote to determine who won the debate. Grading The class is not curved; you will be evaluated on your own merits rather than on how you compare to your peers. Written assignments will be graded according to the following criteria: • Critical thinking and analytic rigor • Conceptual clarity and structure • Use of evidence and course materials • Overall quality of writing and mechanics Grading Standards A B C D F Exceptional work. Demonstrates superb understanding of the course material and outstanding critical thinking and analytic rigor. Goes beyond simply answering the prompt to craft a creative and insightful analysis. Communicates information in a clear, concise, and mechanically correct manner. An A grade will only be given if work is exceptional. Good work. Demonstrates a strong grasp of course material and good analytic rigor, but with some errors (e.g. faulty assumptions in logic or some incorrect descriptions of an author’s argument). May have some problems with structure or mechanics but overall easy to understand the main gist. Solid work, but not the most original or insightful analysis. Mediocre work. Applies some course material and themes, but demonstrates considerable misunderstanding of material. Difficult to discern the student’s argument and the logic supporting this argument. A number of problems with structure and mechanics. Poor work. May attempt to apply some course materials and themes, but demonstrates very serious errors or misunderstanding of course material. The student doesn’t appear to have any argument, and the assignment lacks structure entirely and has extensive problems with mechanics. Shows little effort. Very poor work. Assignment is unrelated to course material and fails to address the prompt and guidelines. Reflects a lack of effort. Academic Misconduct Plagiarism and cheating will not be tolerated. Examples include: turning in a paper written by 5 someone else, quoting someone else’s work without proper citation, and turning in a paper written for another class. Any such misconduct will result in an automatic “F” for the class. The work students submit should be entirely their own. From the Colby Catalogue: Plagiarism, cheating, and other forms of academic dishonesty are serious offenses. For the first offense, the instructor may dismiss the offender from the course with a mark of F (which is a permanent entry on the student's academic record) and will report the case to the department chair and the dean of students, who may impose other or additional penalties including suspension or expulsion. This report becomes part of the student's confidential file and is destroyed six years after graduation or the last date of attendance. A second offense automatically leads to suspension or expulsion. Students may not withdraw passing from a course in which they have been found guilty of academic dishonesty. A student is entitled to appeal charges of academic dishonesty to the Appeals Board. The decision of the board shall be final and binding. The College also views misrepresentations to faculty within the context of a course as a form of academic dishonesty. Students lying to or otherwise deceiving faculty are subject to dismissal from the course with a mark of F and possible additional disciplinary action. Student accountability for academic dishonesty extends beyond the end of a semester and even after graduation. If Colby determines following the completion of a course or after the awarding of a Colby degree that academic dishonesty has occurred, the College may change the student's grade in the course, issue a failing grade, and rescind credit for the course and/or revoke the Colby degree. Electronic Devices Laptops may only be used by those with special learning needs that have consulted with me beforehand. Cell phones should be turned off during class. I will reduce your participation grade if I find you using an electronic device to use the internet or to text. Special Accommodations If you need disability-related accommodations in this class or if you have emergency medical information you wish to share with me, please see me privately after class or at my office. Required Texts • Naazneen Barma and Steven Vogel, eds. 2008. The Political Economy Reader: Markets as Institutions. New York: Routledge. All other readings will be posted on moodle. Students will also watch segments from the PBS documentary series, Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy, which can be found at: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/hi/story/index.html 6 SECTION I: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON POLITICAL ECONOMY Wednesday, September 4: Course Introduction • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 1-18. Monday, September 9: Liberalism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 21-40, 87-116. • Watch Commanding Heights, Chapters 2-7 Wednesday, September 11: Marxism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 41-62. • Leo Panitch, “Thoroughly Modern Marx,” Foreign Policy (May/June 2009), pg. 140-45. • *** Assignment #1 due 10 am via moodle *** Monday, September 16: Mercantilism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 63-86. • Alan Blinder. 2013. After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 210-236. • Lee Hudson Teslik. “Backgrounder: The U.S. Economic Stimulus Plan.” New York Times, January 26, 2009. SECTION II: ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORKS TO STUDY CAPITALISM Wednesday, September 18: Economic Sociology: Polanyi • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 117-151. NOTE: This is dense, difficult reading – read slowly and carefully! • *** Assignment #2 due 10 am via moodle *** Monday, September 23: Economic Sociology: Fligstein • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 153-170. Wednesday, September 25: New Institutional Economics: North and Williamson • Douglass North. 1981. Structure and Change in Economic History. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 3-32. • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 171-194. • *** Assignment #3 due 10 am via moodle *** Monday, September 30: Political Economy: Lindblom • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 239-240 (discussion of Lindblom). • Charles Lindblom, Politics and Markets (1977), pg. 3-13, 65-89, 144-57, 170-188, 20121. 7 SECTION III: DEVELOPED ECONOMIES Wednesday, October 2: Early vs. Late Industrialization • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 195-198; 211228. • Eric Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire (1968), pg. 23-78. • *** Takehome midterm distributed in class *** *** Friday, October 4: TAKEHOME MIDTERM EXAM DUE – 5 PM Monday, October 7: Varieties of Capitalism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 289-326. Wednesday, October 9: Economic Reform and Post-Fordism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 329-354. • Steven Vogel. 2006. Japan Remodeled: How Government and Industry Are Reforming Japanese Capitalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1-21, 51-77, 143-156. Monday, October 14: No Class – Fall Break Wednesday, October 16: Financial Deregulation • Amar Bhidé. 2011. “An Accident Waiting to Happen: Securities Deregulation and Financial Deregulation,” In What Caused the Financial Crisis, ed. Jeffrey Friedman. pp. 69-106. • Joseph Stiglitz. 2011. “The Anatomy of a Murder: Who Killed the American Economy?” In What Caused the Financial Crisis, ed. Jeffrey Friedman. pp. 139-149. • Peter Wallison. 2011. “Housing Initiatives and Other Policy Factors,” In What Caused the Financial Crisis, ed. Jeffrey Friedman. pp. 172-182. • Peter Wallison. 2011. “Credit-Default Swaps and the Crisis,” In What Caused the Financial Crisis, ed. Jeffrey Friedman. pp. 238-248. • Listen to: “The Giant Pool of Money,” episode 355 – This American Life. http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/355/the-giant-pool-of-money *** Assignment #4 due 10 am via moodle *** Monday, October 21: Simulation: Reforming the Financial Sector in the U.S. • Alan Blinder. 2013. After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead. pp. 177-209. *** Tuesday, October 22: FLOATING PAPER DUE – 5 PM SECTION IV. DEVELOPING ECONOMIES Wednesday, October 23: Why Are Some Countries Poor? Three Perspectives • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 425-445. 8 • • Theotonio Dos Santos. 1970. “The Structure of Dependence.” The American Economic Review 60(2): 231-236. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. pp. 70-95. Monday, October 28: Development Strategies: The Developmental State • Peter Evans, Embedded Autonomy (1995), pg. 3-73. Wednesday, October 30: Development Strategies: Economic Liberalization • Nancy Birdsall, Augusto de la Torre, and Felipe Valencia Caicedo. “The Washington Consensus: Assessing a Damaged Brand.” 2010. Policy Research Working Paper 5316, Office of the Chief Economist, Latin America and Caribbean Division. Washington: The World Bank. • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 447-473. Monday, November 4: Development Strategies: Market-Friendly Micro-Institutions • The World Bank, World Development Report 2002: Building Institutions for Markets (2002), 3-27. • Deborah Brautigam and Stephen Knack. 2004. “Foreign Aid, Institutions, and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 52(2): 255-285. Wednesday, November 6: Debate on Foreign Aid • Carol Lancaster. Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics. U of Chicago 2006. pp. 1-24; RECOMMENDED: 25-61. • Dambisa Moyo. 2009. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. pp. 29-68. *** Thursday, November 8: FLOATING PAPER DUE – 5 PM SECTION V. POST-COMMUNIST ECONOMIES Monday, November 11: Communism and its Collapse • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 355-357. • Katherine Verdery. 1996. What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? pp. 19-38. • Valerie Bunce. 1999. Subversive Institutions: The Design and Destruction of Socialism and the State. pp. 20-37. Wednesday, November 13: Shock Therapy vs. Gradualism • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 359-398. • Peter Murrell. 1993. “What is Shock Therapy? What Did It Do in Poland and Russia?” Post-Soviet Affairs 9(2): 111-140. • Watch Commanding Heights, Part II. Chapters 8-9, 12-16, 18-20. 9 Monday, November 18: China’s Economic Model • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 399-427. • Jeffrey Sachs and Wing Thye Woo. 1994. “Structural Factors in the Economic Reforms of China, Eastern Europe, and the Former Soviet Union.” Economic Policy 9(18): 101131. Wednesday, November 20: Will China Democratize? • Minxin Pei. 2006. China’s Trapped Transition: The Limits of Developmental Autocracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 45-95. Monday, November 25: Simulation: The Future of Communism in Cuba *** Tuesday, November 26: FLOATING PAPER DUE – 5 PM SECTION VI. THE FUTURE OF CAPITALISM Monday, December 2: Globalization, the Information Revolution, and the State • Naaz Barma and Steven Vogel, The Political Economy Reader (2008), pp. 483-546. Wednesday, December 4: Debate on Globalization and the Future of Capitalism 10