Urinary Incontinence in Women

Guideline

Background

Prevention

Screening

Diagnosis and Assessment of Severity

Management

Goals

Non-Pharmacologic Options

Lifestyle modifications

Behavioral therapy

Pessaries

Pads and protective garments

Pharmacologic Options

Follow-up/Monitoring

When to Refer to Specialist

Evidence Summary

References

Guideline Development Process and Team

2

2

2

3

4

4

5

5

5

6

7

7

8

8

9

Last guideline approval: February 2013

Guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist patients and providers in choosing appropriate health

care for specific clinical conditions. While guidelines are useful aids to assist providers in determining appropriate

practices for many patients with specific clinical problems or prevention issues, guidelines are not meant to replace

the clinical judgment of the individual provider or establish a standard of care. The recommendations contained in the

guidelines may not be appropriate for use in all circumstances. The inclusion of a recommendation in a guideline

does not imply coverage. A decision to adopt any particular recommendation must be made by the provider in light of

the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

Copyright 2013 Group Health Cooperative. All rights reserved.

1

Background

Prevalence

Urinary incontinence (UI)—the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine—is a common

problem that affects many women of all ages but is more prevalent in the elderly. It is estimated

that UI affects 30–60% of middle-aged and older women in the community, and up to 80% of

female nursing home residents. Despite this high prevalence, UI is both underreported and

undertreated (Goode 2010, Herderschee 2011, Markland 2011, and Keyock 2011). Women are

twice as likely as men to experience incontinence.

Risk factors

Risk factors for UI can be classified as predisposing, obstetric and gynecologic, and promoting factors.

Predisposing factors include race (Caucasian women are more susceptible), genetics, congenital defects

and neurologic abnormalities. Obstetric and gynecologic factors include pregnancy/childbirth/parity, pelvic

surgery and radiotherapy, and pelvic organ prolapse. Promoting factors include increased age,

comorbidities (such as diabetes and vascular disease), changes in mobility, obesity, conditions

associated with increased abdominal pressure, cognitive impairment, urinary tract infection, and

medications such as oral estrogen substitutes, diuretics and anticholinergic agents (Deng 2011).

Types of incontinence

Stress incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine with effort or exertion, sneezing, coughing, or

laughing. These activities result in increased intra-abdominal pressure, which overcomes the sphincter

closure mechanism in the absence of a bladder contraction. It is often caused by weakened pelvic

muscles. Stress incontinence is the most common type of urinary incontinence in younger women.

Urge incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by a

strong desire to pass urine. It is generally caused by an oversensitive bladder. Urge incontinence is more

common in elderly women. In younger women, urge incontinence may be due to interstitial cystitis.

While the term overactive bladder is often used interchangeably with urge incontinence, it has a slightly

different meaning. Overactive bladder is not actually a diagnosis, but refers to a constellation of

symptoms associated with urge incontinence—such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia—which may or

may not include incontinence.

Mixed incontinence is the combination of stress and urge incontinence. Mixed incontinence is the most

common type of urinary incontinence for women overall.

Overflow incontinence is the dribbling and/or continuous leakage associated with incomplete bladder

emptying, often caused by impaired detrusor contractility or, more rarely, by bladder outlet obstruction.

Functional incontinence is any incontinence that is caused by factors outside the lower urinary tract,

such as impaired mobility or manual dexterity, or cognitive impairment.

Prevention

Lifestyle modifications used for treatment are also effective interventions for preventing urinary

incontinence. See page 4.

Screening

Most surveys indicate that fewer than half of women with urinary incontinence report the problem to their

primary care provider. Because UI may have significant impacts on quality of life, including social

withdrawal, depression, and sexual dysfunction, as well as increased risk of falls and urinary tract

infections, it is important that all women are screened for urinary incontinence.

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

2

Screening Recommendation

At every well visit, ask women aged 22 and above: “Is urination or leaking urine a problem

for you?”

This question is included in Group Health’s Well-Visit Questionnaires for women aged 22

and above.

For women who answer “yes,” either on the questionnaire or at the visit, proceed to

diagnosis and severity assessment.

It is important to note that urinary incontinence is primarily a quality of life issue. Many women who have

incontinence do not find the symptoms bothersome enough to warrant treatment. Before going down the

path of diagnosis and treatment, make sure the patient is bothered by her symptoms. If she’s not, no

further action is required.

Diagnosis and Assessment of Severity

History

Assessment of urinary symptoms should include:

• Symptom review

o “Do you ever leak urine when you don’t want to?” (establishes diagnosis)

o “Do you ever leak urine when you cough, laugh, or exercise?” (stress incontinence)

o “Do you ever leak urine on your way to the bathroom?” (urge incontinence)

o “Do you ever use pads, tissues or cloth in your underwear to catch urine?” (addresses

severity of symptoms)

• Past history or current symptoms of urinary tract infection (UTI), dysuria, or hematuria

• Medical problems and prior surgeries

• Consumption of bladder irritants (caffeinated products, alcohol, acidic foods and drinks)

• Excessive fluid intake (more than six to eight 8-oz glasses of fluid per day)

Physical exam

A physical exam may not be required as part of the initial diagnosis, but is recommended if nonpharmacological methods have not improved the patient’s incontinence symptoms. A physical

exam is recommended prior to prescribing medications, and may include:

• BMI (Obesity contributes to incontinence.)

• Abdominal: Palpate for masses, palpate for enlarged bladder

• Pelvic (Use speculum with top blade removed.)

o Rule out vaginal atrophy, pelvic organ prolapse, cystocele.

o Confirm that patient is doing Kegel exercises correctly by feeling for pelvic floor rising and

vaginal narrowing during a bimanual exam.

o Have patient cough to assess for leakage. (Note: The “Q-tip test" is no longer recommended

due to low test specificity.)

• Extremities: Evaluate for edema, which can increase nocturia, especially in frail elderly patients.

• Neurologic: In cases of sudden-onset incontinence, or other neurologic symptoms, test anal wink

reflex, bulbocavernosus reflex, and perineal sensation.

Laboratory evaluation

Urinalysis is recommended to look for:

• Infection (although asymptomatic bacteriuria does not cause incontinence)

• Hematuria

• Dehydration or excessive fluid intake (specific gravity normally 1.010–1.025)

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

3

Management

The goal of management is to reduce urinary incontinence episodes. A multicomponent, stepped

approach focused on the aspects of incontinence the patient considers most bothersome is the key to

successful therapy (DuBeau 2012).

Management Recommendations: Key Points

Start with non-pharmacologic options. Lifestyle modification and behavioral therapy

should be offered as first-line therapy for managing all types of urinary incontinence. These

approaches have no side effects and are more effective than drug therapy. Typically, it

takes a few weeks to 3 months of lifestyle modification and/or behavioral therapy for the full

effects to become noticeable.

Consider adding drug therapy to non-pharmacologic options only for patients whose

urgency or mixed (but not stress) incontinence does not respond adequately to nonpharmacologic options alone. Note that available drug treatments have modest benefit and

are often discontinued because of their high rates of side effects.

Regardless of the approaches used, it is up to the individual patient to determine whether

she considers her incontinence to be successfully managed. Different women will have

different perceptions of what is bothersome and what is tolerable.

Non-pharmacologic options

Lifestyle modifications

Weight loss for moderately and morbidly obese women (see the Adult Weight Management

Guideline).

Dietary change; avoiding foods and drinks that can adversely affect normal bladder function

(caffeinated products, alcohol, and acidic or spicy products).

Smoking cessation for patients with stress UI or stress-predominant mixed UI (see the Tobacco

Use Guideline).

Reduction of fluid intake in patients who are drinking excessive amounts. To avoid the risk of

urinary tract infections, constipation, and dehydration, patients generally should not lower their

intake below six to eight 8-ounce glasses of fluid each day.

Avoiding constipation.

Review of medications that may:

o Cause incomplete bladder emptying (overflow incontinence), such as anticholinergics

(dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl, etc.), antihistamines

(diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, etc.), and beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol,

propranolol, etc.).

o Cause edema, such as calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, felodipine, nifedipine, etc.)

and NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, etc.).

o Cause cognitive changes, such as narcotics.

o Affect bladder function, such as alpha-blockers (doxazosin, prazosin, terazosin), oral or

transdermal estrogen (Premarin, Climara, etc.) and antipsychotics (clozapine,

chlorpromazine, haloperidol, thioridazine, etc.).

o Increase urinary output, such as diuretics (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, etc.)

For those with impaired mobility, reduction of physical barriers to toileting and mobility (e.g.,

selecting clothing that is easier to manage). (See the Fall Prevention Guideline.)

These same interventions are also effective for prevention of incontinence.

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

4

Behavioral therapy

Behavioral therapy, which includes Kegel exercises and bladder training, should be offered as a first-line

therapy for the management of urgency, stress, and mixed urinary incontinence. Behavioral therapy has

been found to be more effective and to provide more sustained improvement in symptoms than

pharmacologic therapy (Burgio1998, Kafri 2008).

Kegel exercises

These should be offered as first-line conservative therapy for women with stress, urgency, or

mixed urinary incontinence.

Kegel exercises are based on the on the principle of strength training, and involve squeezing and

releasing the pelvic floor muscles used to stop urination. These contractions increase the strength

and tone of the pelvic floor muscles, which increases the force of urethral closure, which in turn

prevents stress incontinence during an abrupt increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Kegel

exercises are also helpful in the management of urge incontinence as the detrusor contractions

can be reflexively or voluntarily inhibited by tightening the pelvic floor.

The basic recommended regimen involves 3 sets of 8–12 slow-velocity contractions sustained for

6–8 seconds each, performed 3–4 times a week and continued for at least 20 weeks

(DuBeau 2012).

The success of the treatment depends on the patient’s motivation and ability to perform it

correctly. It is most effective when it is done for at least 3 months, and is more beneficial in

women with stress incontinence. Studies have showed up to 70% improvement in symptoms of

stress incontinence following appropriately performed Kegel exercises (Price 2010).

Bladder training

Bladder training is an appropriate first-line treatment for urgency urinary incontinence, and is also

effective for stress and mixed urinary incontinence. The goal is to have a schedule for voiding

once every 2–4 hours. A woman who feels an urge to urinate outside the schedule should try to

hold it for more and more minutes each time until she can keep the schedule. Timed voiding is

done only when the patient is awake.

Combined Kegel exercises and bladder training

A combination of Kegel exercises with bladder training may be more effective than either one

used alone.

Pessaries

For women with stress or mixed UI with stress predominance, pessaries can reduce episodes of UI.

Pessaries, which can also be used to treat prolapse, are most often used by older women. Younger,

sexually active women tend to be less interested in this option because pessaries must be removed prior

to sexual intercourse, and replacing them can be challenging, especially for women with relatively narrow

vaginas. Fittings for pessaries must be done in the clinic (typically in Gynecology).

Pads and protective garments

Using absorbent products is the most common management strategy among women of all ages with

urinary incontinence. While pads and protective garments are not a form of treatment, they are

useful/effective as:

A coping strategy.

An adjunct to ongoing therapy.

Long-term management of UI after treatment options have been explored.

Long-term management of UI for women who prefer to avoid other forms of treatment.

Pads and protective garments may be the only method of managing UI after treatment of contributing

comorbidities in frail older women with no or minimal mobility, advanced dementia, and/or nocturnal UI

(Thüroff 2011).

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

5

To prevent skin breakdown with the use of pads and protective garments, consider recommending skinbarrier creams, such as Desitin.

Pharmacologic Options

Medications may be effective in some patients with urgency or mixed incontinence (but not stress

incontinence), and may be considered in women who have not achieved satisfactory results with nonpharmacologic options. Caution is advised in prescribing the medications in Table 1, which often cannot

be continued indefinitely because of their side effects, and should be used in combination with behavioral

therapy. All are considered high-risk in the elderly and are contraindicated for patients with dementia.

Drug treatment, when used, should be individualized in light of the patient’s comorbidities and

concomitant medications.

A recent meta-analysis (Shamliyan 2012) showed that drugs used for urgency had a small benefit

compared to placebo and had a high discontinuation rate due to side effects.

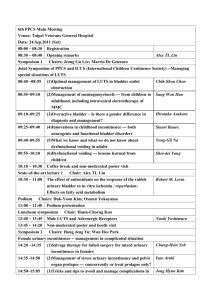

Table 1. Anticholinergic drugs with antimuscarinics effects for patients with urgency or

mixed urinary incontinence

NOTE: Medications are listed in order of preference.

Medication

Dose/frequency

Oxybutynin

immediate-release (IR)

5 mg two to three times daily

For frail elderly patients: 2.5 mg two to three times daily

Oxybutynin

extended-release (ER)

5–15 mg once daily

Oxybutynin

transdermal patch (TD)

3.9 mg/day (one patch) twice weekly (every 3–4 days)

Trospium IR

20 mg twice daily

For frail elderly patients: 20 mg once daily

Trospium ER

60 mg daily

Tolterodine IR

1–2 mg twice daily

Tolterodine ER

2–4 mg daily

Prescribing notes

Side effects of anticholinergics include blurred vision, tachycardia, drowsiness, constipation, urinary

retention, dry mouth, and altered mental status.

Initiation and titration

Begin with a nighttime dose to minimize nocturia and advance as tolerated to the lowest dose with

adequate effectiveness.

Contraindications and cautions

• Anticholinergics are contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow-angle glaucoma or gastric

retention.

• These medications should be used cautiously, especially in elderly women. For elderly/frail

patients, dosing is generally 50% lower.

Trospium is preferred in older adults (over 64 years) with dementia because it has a lower potential to

cross the blood-brain barrier and has fewer drug-drug interactions compared to other oral

antimuscarinics. Also, in limited studies, trospium has not been shown to have a significant impact on

cognitive function in healthy elderly patients.

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

6

Follow-up/Monitoring

Behavioral therapy: Ask patients to follow up in 3 months if they are not satisfied with the results.

Pharmacologic therapy: Consider having patients follow up in 1–2 weeks for assessment of medication

responses, particularly if they are frail and elderly, as these medications can cause especially significant

side effects.

When to Refer to a Specialist

•

•

•

•

•

Refractory incontinence: if the patient desires further evaluation and treatment, refer the patient to

Gynecology or Urology, especially if surgery is being considered.

Significant gynecologic symptoms or uterine prolapse: refer to Gynecology.

Recently diagnosed neurologic changes (e.g., acute-onset urinary incontinence): refer to Urology.

Pessary fitting: refer to Gynecology. May also be performed by women’s health specialists in

primary care.

Patients who don’t understand how to do Kegels or aren’t doing them correctly: refer to PT with

the comment “urinary incontinence.”

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

7

Evidence Summary

Group Health has adapted recommendations from the following externally developed evidence-based guidelines:

•

•

•

•

•

EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence (Thüroff 2011)

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) guideline on treatment of female urinary

stress incontinence (Ghoniem 2008)

French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF) guideline on diagnosis and

management of adult female stress urinary incontinence (Fritel 2010)

NIH/AHRQ guideline on the prevention of fecal and incontinence in adults (Landefeld 2008)

American Urological Association, guideline on diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder

(non-neurogenic) in adults (Gormley 2012)

References

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998 Dec 16;280(23):1995-2000.

Deng DY. Urinary incontinence in women. Med Clin North Am. 2011 Jan;95(1):101-109.

DuBeau CE. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of urinary incontinence. In: UpToDate. Basow DS (Ed),

UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2012.

DuBeau CE. Treatment of urinary incontinence. In: UpToDate. Basow DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA,

2012.

Fritel X, Fauconnier A, Bader G, et al; French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians. Diagnosis and

management of adult female stress urinary incontinence: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of

Gynaecologists and Obstetricians. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Jul;151(1):14-19.

Ghoniem G, Stanford E, Kenton K, et al. Evaluation and outcome measures in the treatment of female urinary stress

incontinence: International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) guidelines for research and clinical practice. Int

Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunc. 2008 Jan;19(1):5-33

Goode PS, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland AD. Incontinence in older women. JAMA. 2010 Jun 2;303(21):21722181.

Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults:

AUA/SUFU Guideline. 2012 May. American Urological Association.

Kafri R, Shames J, Raz M, Katz-Leurer M. Rehabilitation versus drug therapy for urge urinary incontinence: long-term

outcomes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunc. 2008 Jan;19(1):47-52.

Keyock KL, Newman DK. Understanding stress urinary incontinence. Nurse Pract. 2011 Oct;36(10):25-36.

Landefeld CS, Bowers BJ, Feld AD, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement:

prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 18;148(6):449-458.

Markland AD, Vaughan CP, Johnson TM 2nd, Burgio KL, Goode PS. Incontinence. Med Clin North Am. 2011

May;95(3):539-554.

Price N, Dawood R, Jackson SR. Pelvic floor exercise for urinary incontinence: A systematic literature review.

Maturitas. 2010 Dec;67(4):309-315.

Shamliyan T, Wyman JF, Ramakrishnan R, Sainfort F, Kane RL. Benefits and harms of pharmacologic treatment for

urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jun 19;156(12):861-874.

Thüroff JA, Abrams P, Andersson KE, et al. EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2011 Mar;59(3):387400.

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

8

Guideline Development Process and Team

Development Process

To develop the Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline, Group Health adapted recommendations from

externally developed evidence-based guidelines and/or recommendations of organizations that establish

community standards. For details, see Evidence Summary and References.

This edition of the guideline was approved for publication by the Guideline Oversight Group in February

2013.

Team

The Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline development team included representatives from the

following specialties: family medicine, geriatrics, nursing, obstetrics/gynecology, pharmacy, and urology.

Clinician lead: Chris Thayer, MD, Medical Director, Clinical Knowledge Support, thayer.c@ghc.org

Guideline coordinator: Avra Cohen, MN, Clinical Improvement & Prevention, cohen.al@ghc.org

Ladd Carman, PharmD

Kristin Conn, MD, Family Medicine

Mary Jane Lambert, MD, Geriatrics

Kathryn Ramos, Health Education Specialist, Clinical Improvement & Prevention

Nadia Salama, MD, Epidemiologist, Clinical Improvement & Prevention

Karen Severson, RN, Nursing Operations

Wendy Siu, MD, Urology

Ann Stedronsky, Clinical Publications, Clinical Improvement & Prevention

Susan Warwick, MD, Ob/Gyn

Mary Wechsler, ARNP, Urology

Urinary Incontinence in Women Guideline

9