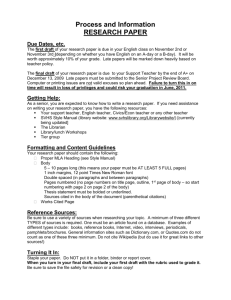

Research Paper Handbook - the Parsippany

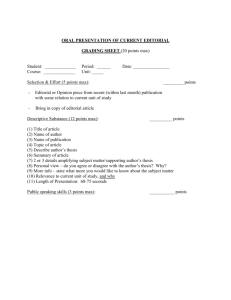

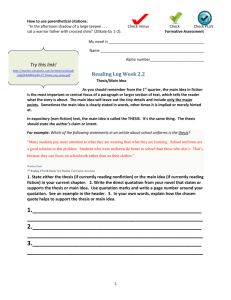

advertisement