YOUREE-THESIS - Digital Collections at Texas State University

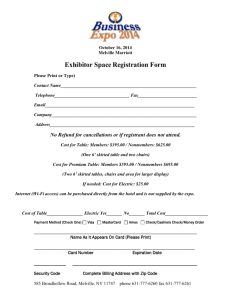

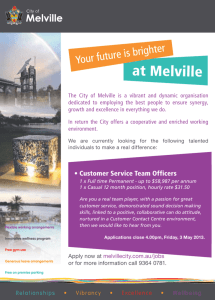

advertisement