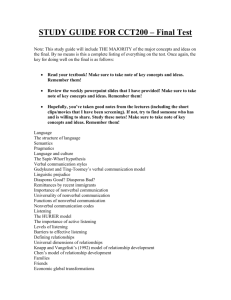

Intercultural Communication I

advertisement

Intercultural Communication I Table of contents Intercultural Communication I I Defining Intercultural Communication __________________ 03 Stella Ting-Toomey's Definition The Iceberg Metaphor II Cultural Values ______________________________________ 04 Models of Value Orientations Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck's Value Orientations Three of Hofstede's Cultural Variables in Organizations ____ 05 III Perception and Intercultural Communication ____________ 06 IV Communication Styles _______________________________ 08 Continua of Communication Styles ____________________ 09 V Non Verbal Communication ___________________________ 11 Developing Non Verbal Communication Competencies ____ 12 VI Culture Shock _______________________________________ 13 Some Strategies for Surviving Culture Shock ____________ 14 VII Bibliography ________________________________________ 15 I Defining Intercultural Communication Stella Ting-Toomey's Definition Although there are many definitions of intercultural communication, the one proposed by Stella Ting-Toomey is especially interesting. According to this scholar, the necessary elements of intercultural communication are: • Two people (or two groups)… • of different cultures (with the definition of «culture» being quite broad)… • in interaction… • who negotiate common meaning. The fourth item in the definition is particularly interesting, because it underlines the importance of not merely trying to communicate but also trying to understand – which is rather more complex and difficult. as those involving power, dependence and influence) can generate contradictions between the two parts of the so-called cultural iceberg, and context also influences how well the metaphor works. But the image remains useful for clarifying important relationships which surround ideas about culture. The image becomes especially provocative when we consider intercultural interaction, or intercultural communication between two icebergs. We can ask: When we perceive another, are we viewing only the visible parts of that iceberg? On what can we base our perceptions and interpretations, when so much of that iceberg is invisible? Can we truly understand what we see in the other, if we are unaware or ignorant of the invisible parts of that iceberg? What if we are also unaware or ignorant of the invisible parts of the iceberg on which we stand? Most of the workshop is designed to make more visible powerful but often invisible differences in cultural values, communication styles, and conflict styles which influence interaction between people and groups from different cultures, and thus influence our ability to negotiate common meaning interculturally. The iceberg metaphor is often used to talk about culture. In an iceberg, there is both a visible and an invisible part, and the invisible part is larger and more important for stability and for those who must navigate near it. In speaking of culture, the visible parts (architecture, food, behaviours, institutions, the arts, etc.) rest upon a larger invisible part (cultural values, norms, beliefs) which provide the foundation and meaning for what is visible. Granted, some cultural interactions (such Christopher Drew The Iceberg Metaphor 3 II Cultural Values When one speaks of intercultural communication, one speaks inevitably of cultural values. Whether we are conscious of them or not, values are an important, generally invisible part of our culture. Values form the basis of all our attitudes and actions, and this brings us into harmony or conflict with the cultural values of groups in which we are members. Values are also the lenses through which we view and evaluate the attitudes and actions of others. As intercultural scholar Stella TingToomey observes, values «set the background criteria for how we should communicate appropriately with others. They also set the emotional tone for how we interpret and evaluate cultural strangers' behaviours.» 4 Models of Value Orientations The importance of the connection between cultural values and behaviour (and specifically between cultural values and communication and conflict styles) can be explored using the work of two well-known models of cultural value orientations. Geert Hofstede and Florence Kluckhohn (working with her colleague Fred Strodtbeck) offer models based on extensive international and intercultural research. These models provide a useful place to start in considering what our own cultural values might be and how these could contrast with those of others we interact with interculturally. Kluckhohn et Strodtbeck's Value Orientations Orientation People and Nature Range of Value Orientations Subordination to Nature Harmony with Nature Mastery over Nature Past Oriented Present Oriented Future Oriented Human Nature Basically Evil (mutable / immutable) Neutral or Good and Evil (mutable / immutable) Basically Good (mutable / immutable) Human Activity Being Being in Becoming Doing Social Relations Lineality (authoritarian decisions) Interdependence (group decisions) Individualism (autonomy) Time Sense Klukhohn and Strodtbeck (1961); summary based on Ting-Toomey (1999) Three of Hofstede's Cultural Variables in Organizations (53 countries surveyed) Individualist Cultures Collectivist Cultures «I» identity «We» identity Individual goals Group goals Inter-individual emphasis In-group emphasis Voluntary reciprocity Obligatory reciprocity Management of individuals Management of groups Groups which Hofstede found had a high percentage of Individualists: USA, Australia, Great Britain, Canada, Holland, New Zealand, Sweden, France and Germany. Groups which Hofstede found had a high percentage of Collectivists: Guatemala, Ecuador, Panama, Indonesia, Pakistan, Taiwan/People’s Republic of China, Japan, Burkina Faso, Kenya. 5 Low Power Distance Cultures High Power Distance Cultures Emphasize equal distance Emphasize power distance Individual credibility Seniority, age, rank, title Symmetrical interaction Asymmetrical interaction Emphasize informality Emphasize formality Subordinates expect to be consulted Subordinates expect directions Groups which Hofstede found tended toward Low Power Distance: Austria, Israel, Denmark, New Zealand, Republic of Ireland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Canada, USA Groups which Hofstede found tended toward High Power Distance: Malaysia, Guatemala, Panama, Philippines, Arab nations, India, Mauritania, Mali, Singapore Weak Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures Strong Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures Uncertainty is valued Uncertainty is a threat Career change Career stability Encourage risk taking Expect clear procedures Conflict can be positive Conflict is negative Expect innovations Preserve status quo Groups which Hofstede found tended toward Weak Uncertainty Avoidance: Singapore, Jamaica, Denmark, Sweden, Hong Kong, USA, Canada, Norway, Australia Groups which Hofstede found tended toward Strong Uncertainty Avoidance: Greece, Portugal, Guatemala, Uruguay, Japan, France, Spain, South Korea Note: The cultures mentioned are based on the majority tendencies in organizations within these countries. Hofstede (1991); summary based on Ting-Toomey (1999). As Ting-Toomey says, cultural values provide both background and fundamental guidelines for most of our behaviors, feelings, judgments and attitudes. Our culture teaches us important values which structure our perceptions, which influence our preferred communication and conflict styles, and which shape the non verbal norms that we develop. III Perception and Intercultural Communication 6 Because of the invisible yet powerful filtering effect of cultural values, we can observe different perceptions and interpretations of «the same» situation or word or moment of silence, even within a single culture. If people are interacting from different cultural backgrounds and values, the potential for different perceptions is even greater. Therefore, the concept of perception is central when we think about intercultural communication. In the workshop, participants first encounter perceptual differences when the group views an image of [a rabbit/duck, an Indian/Inuit] The discussion of these images reveals that, in differences of perception, the question is not, Who is right or who is wrong? but rather, How can we see the same thing so differently that it results in not seeing «the same thing» at all? Next, participants explore a sentence to discover different ways its meaning might be perceived. By the end of this process, dramatic differences in perception clearly emerge, even from statements that seem extremely «obvious». Example of sentences: My son is sick. All parts of this unexceptional sentence can be perceived in many different ways: Who is speaking: Most often, one imagines the mother, but why could it not also be the father? Son: What is a son? A child of my blood? A child I have adopted? A child that concerns me, whom I raise, but not of my bloodline (close family or distant, or from a circle of friends)? Any child of my extended family? Any child of my culture, my people? How old is the son? Child (the usual perception) or adult? Is: Suddenly? Always? Seriously or a little unsettled? Sick: Physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually? I'm going to Kosovo, to participate in a reconciliation project. I: As a foreign expert? A Kosovar? A man or a woman? Reconciliation project: Between who and whom? Albanians and Serbs (the typical perception), or between two Albanian families, or between two brothers of the same family? Am I a participant in the conflict, or do I have a role as mediator? Kosovo: If I had said, «Kosova», what would be the difference, and for whom? The children lower their eyes in the presence of the teacher. Lower their eyes: A sign of having misbehaved, of fear, of shame, or of respect? Is this the normal or an unusual situation in class? Teacher: The title for a Professor? Or for any teacher? Male or female? You are in Zimbabwe. One morning a local colleague tells you that he had a dream about his grandfather who has been dead for several years. The next day, he doesn't come to work.. Dream: The work of the subconscious, or a message from the ancestors? Grandfather: An old man whom one knows vaguely and sees rarely? The most important man in the family or the community? Wise? Forgetful? Dead: No more interaction now possible with this person? Or the beginning of an essential relationship with the ancestor? Second sentence: Is not coming to work related to the dream, or unrelated? Is the first sentence the sharing of a dream (= direct communication) or the announcement of an absence of several days (= indirect communication)? At the conclusion of this module, participants share what they have learned about perception in intercultural contexts: • My perception is justified and OK. • The other's perception is justified and OK. • My perception is relative and incomplete. • The other's perception is relative and incomplete. • Our background, history, and context shape our perceptions. • I need the help of the other to see what he or she sees. • The other needs my help to see what I see. • If I feel my perception is respected, I am more able to respect the perception of the other and to enter into a constructive dialogue, and vice versa. • Experiences in common are a key for expanding perceptions. • Time can help expand our perception of a situation as we reflect on new information, awareness, and experience. • Exploring the perception of another does not mean denying my own. If we genuinely wish to negotiate shared meaning across cultures, we must give up the idea that what we perceive is agreed upon by «everyone» and that our interpretations are «obvious.» What matters in intercultural communication is not whose perception is «right,» but rather why I perceive what I perceive, and why you perceive what you perceive. Once such a conversation begins, we can work toward creating shared meaning. As time passes and we explore our own and others' perceptions, we may become aware that what we perceive when encountering different cultural values can shift, depending on our own values and on what we learn about value while interacting with other cultures. How we perceive the world can change as we learn and grow interculturally. 7 8 IV Communication Styles The manner of expressing oneself with words, of communicating with words, varies dramatically from one culture to another, and indeed from one person to another in a single culture. To be speaking the same language is not necessarily to speak «the same language.» Each person has a preferred way of communicating. The preferred communication style, just like more general cultural values, provides the basic strategies we use to open conversations with others and also the background standards with which we interpret and evaluate their communication – that is, our communication style shapes how we perceive and react to communication events. A variety of communication styles have been developed over centuries and generations, closely linked with cultural values, norms and behaviors of associated groups and individuals. To learn about these styles, to become conscious of one's own styles, and to be able to recognize the styles used by our conversational partners greatly contributes to better intercultural understanding. As with perception, no communication style is better than any other, and all styles allow for the discussion of all subjects. Problems do arise, however, when a person using one communication style fails to understand or respect communication styles that are different. To be able to recognize communication styles and to respect each of them is the first step in developing intercultural competence. To be able to modify one's listening strategies in order to understand meanings communicated in a style different from one's own is the next step. The final step – a bit more difficult but proof of intercultural competence – is to be able to adapt one's own communication style to different contexts and, little by little, learn to communicate in styles which match those of another. Continua of Communication Styles Linear Communication Style Circular Communication Style This style develops an argument that comes to a conclusion and presents it in a very explicit manner. A speaker often tells the listener «the point» or tries to explain precisely the intended meaning. This style gives all necessary contextual elements which listeners can connect to understand what the speaker means. A speaker avoids explicitly stating any one «point». Circular communicators feel that, although they might Linear communicators feel they speak quickly and efficiently, because they use straightforward logic and speak at length, once they have spoken, all elements necessary for understanding are clear. they state points explicitly. They sometimes feel Circular communicators talk too much without ever getting to the point. They sometimes feel Linear communicators are simplistic, leaving out information needed for understanding. Direct Communication Style Indirect Communication Style In this style, the message is to be sought within the words used and not in the surrounding context. Speakers in this style say exactly what they mean and tend to give priority to the content of communication exchanges. In this style, the message is to be sought outside the words used, in a variety of elements: proverbs, metaphors, silence, and surrounding contexts. Speakers in this style tend to give priority to relationships and harmony among those present. Direct communicators feel that they are frank and that they speak honestly. They think that focusing on content is efficient and practical and that how people feel about the content is a separate subject. Indirect communicators feel that they are considerate and sensitive to the complexity of issues, particularly those involving important experiences like birth, rituals, sexuality, death, etc. They feel that focusing on relationships is wise in the long term. They sometimes feel that Indirect communicators are not honest or that they avoid saying «what they really mean.» They sometimes feel that Direct communicators are too blunt and hurtful. Emotionally Expressive Style Emotionally Restrained Style This style prefers to show emotions, such as joy, sadness, disappointment, anger, and fear. The underlying idea is that, in order to respect others and create connected relations, one should let them know what one is experiencing. This style prefers to hold emotions within and manage them there. The underlying idea is that, in order to respect others and maintain harmonious relations, one should avoid forcing one's own feelings on them. Expressive communicators feel alive and engaged when they express and receive emotional expressions, even negative emotions. Restrained communicators feel respectful and responsible when they contain and manage their emotions. They sometimes feel that Restrained communicators are cold or not interested in either the issues or in the other person. They sometimes feel that Expressive communicators are immature because they cannot control their emotions and that they lack respect for the needs of others. Concrete Communication Style Abstract Communication Style This style prefers to use examples, stories, actual cases, and real situations to reinforce communication messages. This style prefers to use theories, concepts, and abstract ideas to explain communication messages. Concrete communicators feel that their stories and cases are the base from which abstract ideas are developed. Abstract communicators feel that theories and concepts provide the framework necessary to understand relationships among concrete details. They sometimes feel that Abstract communicators They sometimes feel that Concrete communicators are out of touch with their listeners and are too vague. are too personal and unsophisticated. In each workshop, participants explore how their own preferred communication styles influence their perceptions of other styles. They then discuss strategies which might allow them to interact more fruitfully with contrasting styles. 9 10 Common suggestions for improving intercultural communication across styles include: Linear Style → Circular Circular Style → Linear • Be patient, do not interrupt too quickly. Stop waiting for the point! • If the response seems too brief, ask questions • Listen to interpret, to make connections among elements • Listen to synthesize and reformulate • Don't forget that relationships matter • Try to select and choose what you will say, perhaps giving a linear response and then adding context Direct Style → Indirect Indirect Style → Direct • Lose faith in the words – look behind words • Try not to feel attacked • Remember that relationships matter • Remember that direct communicators value directness – they tend not to mean or take things personally • Learn to use metaphors and proverbs that communicate the point • Prefer facts to metaphors • Think about the impact of words you choose; practice diplomacy • Try to say exactly «what you mean» A good interpreter is someone who is able to translate not only words but also communication styles. This explains why a long statement in one style may be much shorter when translated to another, and vice versa. It is not necessary to become a trained interpreter, however, to learn to respect and appreciate a variety of communication styles. We can begin by becoming aware of our own preferred styles and then learning ways to show respect for other styles we encounter. In this way, we take the first important steps on a journey toward intercultural communication competence. V Non Verbal Communication Like verbal communication, non verbal communication in intercultural situations requires attention, understanding, and the development of specific competencies. One might say that verbal communication is digital while non verbal communication is analogic. Although verbal communication has many dimensions (such as pauses, word choice and context), the dimensions of non verbal communication are much broader and, often, communicate from a zone which is outside the awareness of both speakers and listeners. As will be understood from the list below, non verbal communication takes place on many levels at the same time and often can be seen or felt as well as heard. Since many levels of non verbal communication are not carried in language, and since non verbal can be simultaneously intentional and unintentional, it can create powerful emotional meaning and misunderstandings in ways both the speaker and the listener may not understand. The main dimensions of non verbal communication are: • Face and body movements – use of arms and hands and head, eyebrows and mouth – in both conscious and unconscious ways • Eye contact • Tone of voice and volume • Spatial orientation – How close or how far apart do people stand when interacting? Are they faceto-face or turned to one side? • Touch • Environment – shape and arrangement of rooms, furnishings, architecture • Time and how it is used in conversation, appointments, etc. • Silence Modern intercultural communication scholars have shown that 65% to 90% of any communication is contained in non verbal cues. What is even more powerful is that most studies suggest that non verbal messages can override the verbal message, either reinforcing or contradicting it. This means, for example, that someone may say verbally, «Welcome! I'm so glad to see you,» but if their non verbal cues (tone of voice, eye contact, turning the head, hand or arm gestures) indicate that we are not really welcome, we are likely to trust the non verbal message more. Just as each culture and each person prefers different verbal communication styles, cultures and persons also use different non verbal communication cues. People use non verbal cues to communicate feelings, to express friendship and humor and irony, warning and power relations, questions and trust. We begin to absorb the inarticulate, non verbal cues of our home culture very soon after birth. But the non verbal 11 12 For example: To express respect in some cultures, children are taught to look at adults who are speaking. In others cultures children are taught not to look directly at adults to express respect. munication partner is operating very differently from you, and be aware of the effort and the uncertainty this generates for you. • Experience films from a «non verbal communication perspective». They can be a rich source of nonjudgmental learning and training. • Train yourself to seek the «why and wherefore» of non verbal expressions, instead of judging them. Learning to recognize non verbal communication conventions of another culture can be as challenging as learning the verbal language, but at least as important. In intercultural interaction around non verbal, there is no simple approach, but there is one golden rule: Observing, trying to understand, and adapting one's own non verbal can contribute to mutual understanding in any intercultural communication process. The non verbal dimension of intercultural communication is fascinating and challenging because, like for the iceberg, we see the visible dimension, and are frequently unaware of the more important invisible dimension that give meaning to the visible. Thus, our perception and interpretation of non verbal is frequently inaccurate, based on our values and norms, rather than on the other person's. codes of others can be hard to identify and decode. It is easy to confuse them with our native codes or to interpret them using our own (often inappropriate!) norms. Developing Non Verbal Communication Competencies In order to develop your non verbal communication competence, try to: • Become more aware of how your own non verbal codes work and of the cultural norms and values which underlie them. • Observe without judgment the non verbal of people around you. • Practice adapting your non verbal (eye contact, use of space, tone of voice, touch) when your com- VI Culture Shock What happens when a human being – by nature resistant to change – must face numerous changes for a long period of time, as is the case when a person chooses to live for months or even years in a new culture? At first, many people find the new world interesting and seem to function quite adequately. But eventually signs of resistance appear, especially for people who truly attempt to integrate themselves with the new culture. Such integration requires us to modify, even to abandon central behaviours, beliefs and values which give meaning to life and which help to define our identity. Whether simple or fundamental, a huge number of changes – in communication styles, in eating habits, in language, in perceptions, in dress – surround people who live in new cultural contexts. And familiar styles, habits, perceptions, and dress are either absent or are misunderstood. Every hour, every day the person is pushed to learn, to adapt, and to develop ways to survive and function in the new world. Reserves of energy are slowly exhausted and the threshhold of resistance is lowered. At bottom, something is falling apart ... and culture shock is near. Culture shock is the temporary disintegration of one’s central identi- ty, one's sense of self. This disintegration occurs when persons are forced to accept that they have become incapable of constructing any stability in their world, incapable of making reliable meaning in a new context. Such disintegration is accompanied by feelings of grief – one is losing the self one has always known, losing the habits and behaviours one has always practiced, losing the values that have always given meaning to things, and which we often were not even aware of. The moment when everything seems to dissolve is potentially a moment of great openness to the world. From the moment we stop clinging to our culture of origin, we open the door to the new world which surrounds us. If the moment of disintegration is accepted with awareness, gentleness and openness, the letting go can be a first step toward genuine integration into the new culture. The process of learning and adapting in a new culture is very tiring and unsettling. It generates uncertainty, stress and resistance, and thus requires a great deal of energy and strength, especially for people who expect themselves to carry on in their work and social life. Yet this energy disappears at some stage of the process, as the cultural adaptation curve shows: 13 14 The Culture Shock acculturation before arrival departure 4 months 8 months 2 years 3 years recovery euphoria of the first weeks first signs of tension identity problems crisis level of good functioning getting back to normal people who leave the country Dinello Some Strategies for Surviving Culture Shock During the time of culture shock, it is important to practice the following: • Try not to judge yourself too harshly – for being tired or for making mistakes or for thinking in negative ways you find uncomfortable. • Try not to blame the host culture for problems. Rather, try to understand how your home culture and the host culture have failed to mesh. • Be quick to laugh, especially at yourself as you learn and learn again from each experience. • Practice safe stress reduction techniques which work for you, for example, meditation, safe exercise, healthy diet, relaxing companions, appropriate dance and music, taking a break from anything that feels like work. Understanding that culture shock is a process which ebbs and flows can help a person survive and even thrive during this challenging but rewarding experience. Being aware of the energy curve, one can be more careful to take care of oneself during times of low energy, and observe and learn from one’s process of integration during the period of «culture shock». And most important, remember : Like a butterfly in a cocoon, you are constructing a new you within the new culture. . .and this takes time. VII Bibliography The art of crossing cultures / Craig Storti. – Boston; London: Brealey Publishing, 2001. – xviii, 153 p. ISBN: 1-85788-296-2 Basic concepts of intercultural communication / Milton J. Bennett (Ed.). – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1998. – 270 p. ISBN: 1-877864-62-5 Beyond chocolate: understanding Swiss culture / Margaret OertigDavidson. – Basel: Bergli Books, 2002. – 239 p. ISBN: 3-905252-06-6 *China wakes: the struggle for the soul of a rising power / Nicholas Kristof. – New York: Vintage, 1994. – 528 p. ISBN: 0679763937 Communicating across cultures / Stella Ting-Toomey. – New York; London: The Guilford Press, 1999. – XIII, 310 p. (The Guilford communication series). ISBN: 1-57230-445-6 *Communication and culture / C. Gallois, V. Callan. – Chichester: Wiley, 1997. – 172 p. ISBN: 0-471-96622-3 Communication highwire: leveraging the power of diverse communication styles / Dianne Hofner Saphiere, Barbara Kappler Mik, Basma Ibrahim DeVries. – Yarmouth; Boston; London: Intercultural Press, 2005. – XVI, 286 p. ISBN: 1-931930-15-5 Cross-cultural dialogues: 74 brief encounters with cultural difference / Craig Storti. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1994. – 140 p. ISBN: 1-877864-28-5 *Cultural intelligence: people skills for global business / David C. Thomas, Kerr Inkson. – San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2003. – XIV, 222 p. ISBN: 1-57675-256-9 Cultural metaphors: readings, research translations, and commentary / Martin J. Gannon. – Thousand Oaks; London; Delhi: Sage Publications, 2001. – X, 262 p. ISBN: 0-7619-1337-8 Culture in Finnish development cooperation / Veikko Vasko… [et. al.]. – Helsinki: Department for International Development Cooperation, 1998. – 190 p. ISBN: 951-724-208-5 *Cupid's wild arrows: intercultural romance and its consequences / Dianne Dicks. – Weggis: Bergli Books, 1993. – 295 p. ISBN: 3952000221 15 *Entertainment education: a communication strategy for social change / Arvind Singhal. – Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 199. ISBN: 0805833501 Exploring culture: exercises, stories, and synthetic cultures / Gert Jan Hofstede, Paul B. Pedersen, Geert H. Hofstede. – Yarmouth, Me.: Intercultural Press, 2002. – xix, 234 p. ISBN: 1-877864-90-0 16 *Improving intercultural interactions: modules for cross-cultural training programs, vol. 2 / Richard W. Brislin, Kenneth Cushner. – London: Sage Publications, 1997. – 321 p. – (Multicultural Aspects of Counseling; Series 8) ISBN: 0-7619-0537-5 Kiss, bow, or shake hands / Terri Morrisson, George A. Borden. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1994. – 440 p. ISBN: 0140095365 Figuring foreigners out / Craig Storti. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1999. – 184 p. ISBN: 1-877864-70-6 Naga and Garuda: the other side of development aid / Rudolf Högger. – Kathmandu: Sahayogi, 1998. – 309 p. GenXpat: the young professional's guide to making a successful life abroad / Margaret Malewski. –Yarmouth; Boston; London: Intercultural Press, 2005. – XIV, 219 p. ISBN: 1-931930-23-6 Navigating culture: a road map to culture and development / Pekka Seppälä. – Helsinki: Department for International Development Cooperation, 1998. – 60 p. ISBN: 951-724-245-X Handbook of intercultural training / Dan Landis (Ed.). – Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004. – XII, 515 p. ISBN: 0-7619-2332-2 Old world, new world: bridging cultural differences: Britain, France, Germany and the U.S. / Craig Storti. – Yarmouth, Me.: Intercultural Press, 2001. – ix, 276 p. ISBN: 1-877864-86-2 The healing wisdom of Africa: finding life purpose through nature, ritual, and community / Malidoma Patrice Somé. – New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1999. – 321 p. ISBN: 0-874-77991-X Images, cultures, communication: images, signs, symbols: the cultural coding of communication / SIETAR Europa. – Paris: SIETAR, 1997. – 485 p. ISBN: 952-90-9075-7 *Improving intercultural interactions: modules for cross-cultural training programs / Richard W. Brislin, Tornoko Yoshida. – London: Sage Publications, 1994. – 354 p. – (Multicultural Aspects of Counseling; Series 3). ISBN: 0-8039-5410-7 *A plague of caterpillars: a return to the African bush / Nigel Barley. – Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. – 158 S. Riding the waves of culture: understanding cultural diversity in business / Fons Trompenaars. – London: N. Brealey, 1995. – 192 p. ISBN: 1-85788-033-1 Ticking along with the Swiss / Diane Dicks (Ed.). – Riehen: Bergli Books, 1993. – 195 p. ISBN: 3-9520002-4-8 Where in the world are you going? / Judith M. Blohm. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1996. – 63 p. ISBN: 1-877864-44-7 Women's guide to overseas living / Nancy J. Piet-Pelon, Barbara Hornby. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1992. – 221 p. ISBN: 1-877864-05-6 The xenophobe's guide to The Swiss / Paul Bilton. – London: Oval Books, 1999. – 64 p. – 2nd ed. ISBN: 1-902825-45-4 52 activities for exploring values differences / Donna M. Stringer, Patricia A. Cassiday. – Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 2003. – XVI, 249 p. ISBN: 1-877864-96-X Websites Films The Centre for Intercultural Communication offers services and programs designed to address the challenges faced by organizations and individuals in international and multicultural settings: www.cic.cstudies.ubc.ca/index. html East is east / Regie: Damien O'Donnell. – Grossbritannien, 1999. – 96 Min. Die Engländerin Ella und der Pakistaner George sind seit 25 Jahren verheiratet und haben sechs Söhne und eine Tochter mit ihrem kleinen Fish&Chips-Geschäft in einem Vorort von Manchester grossgezogen. Am Beispiel der Kinder wird die Auseinandersetzung des Individuums im Schnittpunkt unterschiedlicher kultureller Positionen thematisiert. Besonders deutlich werden diese Positionen im Bezug auf geschlechtsspezifische Verhaltensweisen und Vorstellungen. Konfliktpotenzial entfaltet sich sowohl zwischen Vater und Kindern als auch zwischen den Ehegatten. Intercultural Communication Homepage: This site is intended for those studying intercultural communication as part of career preparation, and contains recommended reading and other resources: www2.soc.hawaii.edu/com/resources/intercultural/Intercultural. html The Integrated Resources Group provides solutions to cross-cultural problems utilizing project-specific and context-appropriate resources, for example resources for expatriates and repatriates: www.expat-repat.com The Web of Culture: a consulting firm and website which seeks to educate its visitors on the topic of cross-cultural communications online today: www.webofculture.com SIETAR: Society for Intercultural Education Training and Research: www.sietar-europa.org The Intercultural Communication Institute is designed to foster an awareness and appreciation of cultural difference in both the international and domestic arenas by educational means: www.intercultural.org ID Swiss / Regie: Fulvio Bernasconi, Christian Davi, Nadia Fares, Wageh George, Kamal Musale, Thomas Thümena, Stina Werenfels. – Schweiz 1999. – Produktion: Dschoint Ventschr Filmproduktion. – 90 Min. Sieben Schweizer Filmschaffende der jüngeren Generation, mehrheitlich ausländischer Abstammung, dokumentieren Begegnungen verschiedener Kulturen in unserem Land: ein junger Mann mit indischer Herkunft versucht, seine attraktive Schweizer Bekannte mit einem Curry-Raclette zu bezirzen; ein ägyptischer Einbürgerungskandidat will von seinen Freunden in der Heimat wissen, ob er ein guter Schweizer werde; ein italienischer Secondo befindet sich im Dilemma, ob er beim Fussball die schweizerische oder die italienische Nationalmannschaft unterstützen soll. Moi et mon blanc / Regie: Pierre Yameyogo. – Burkina Faso, 2004. – 90 Min. Vergnügliche und kluge Komödie, die das (Über-)Leben in der multikulturellen Gesellschaft von heute als eigentliches Abenteuer begreift. Mamadi, ein junger Mann aus Burkina Faso studiert in Paris. Als das Stipendium von zuhause ausbleibt, muss er sich mit Schwarzarbeit das Leben finanzieren. Hier lernt er den Franzosen Franck kennen, mit dem er nach einem grossen Geldfund nach Afrika abhaut. Der Länderwechsel funktioniert als Spiegelungsachse. Ausgehend von den eigenen Erfahrungen, die er als Schwarzer in Paris machte, zeichnet der Regisseur anhand kleiner Alltäglichkeiten die Komplexität kultureller Unterschiede – und Gemeinsamkeiten – auf. Just a kiss / Regie: Ken Loach. – Grossbritannien, 2004. – 104 Min. Casim, Sohn pakistanischer Einwanderer, ist ein erfolgreicher DJ in Glasgow. Seine Eltern sind streng gläubige Muslime. Fürsorglich und familienbewusst planen sie die Heirat Casims mit seiner Cousine. Ihre Pläne drohen sich zu zerschlagen, als Casim Roisin kennen lernt, die Musiklehrerin seiner jüngeren Schwester. Zwischen den beiden funkt es auf Anhieb. Doch Casim weiss nur zu gut, dass seine Eltern, ganz unabhängig von ihren Verheiratungsplänen einer Ehe mit einer Europäerin niemals ihr Einverständnis geben würden. Auch Roisin muss feststellen, dass ihre katholische Umgebung ihrer Liebe eher skeptisch gegenübersteht und sie in keiner Weise unterstützt. Q-Begegnungen auf der Milchstrasse / Regie: Jürg Neuenschwander. – Schweiz, 2000. – 94 min. Drei Viehzüchter aus Mali und Burkina Faso reisen in die Schweiz zu drei Berufskollegen im Seeland und im Berner Oberland. Zurück in ihrer Heimat berichten sie von ihren Erfahrungen im Alpenland. Wo ist das Vertraute im Fremden, wo das Fremde im Vertrauten? Im Wechsel der Perspektiven geraten gängige Vorstellungen von Kuh und Milch, Markt und Fortschritt, Mensch und Natur in Bewegung. Im Film geht es um Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede, um Veränderung, um Vertrautes und Neues in Afrika und in der Schweiz. Va, vis et deviens / Regie: Radu Mihaileaunu. – Brasilien, Frankreich, Israel, Italien, 2005. – 140 Min. Äthiopien, 1984 vor dem Hintergr- 17 und der Rettungsaktion «Operation Moses»: Eine Christin rettet ihren Sohn David vor der Hungersnot, indem sie ihm befiehlt, sich als Jude auszugeben, so dass er an Bord der rettenden Maschine nach Israel gelangen kann. David wird in Israel von einer linksliberalen Adoptivfamilie aufgenommen, die alles unternimmt, damit er sich wohl fühlt. Davids Identität wird immer wieder von neuem im Frage gestellt: Sei es, dass der religiöse Vater seiner Freundin ihn nicht akzeptiert, oder sei es, dass sein zionistischer Adoptivvater von ihm verlangt, Militärdienst zu leisten – immer wieder muss sich David fragen, wer er ist und wo seine Wurzeln sind. 18 The virtual team : managing culture and technology / ed. by bigworldmedia. – USA, 2002. – 20 Min. In this cutting-edge dramatization, you'll take your students on a revealing journey through cyberspace, and discover the profound effects of cultural differences and time on a virtual team. You'll meet the leader of a global operation, and observe the challenges she faces trying to lead her managers on a multicultural virtual team. Designed to stimulate lively discussion and reflection, this program will help everyone find out the secrets to cultural success in the modern workplace. Based on in-depth research and expert articles on implementing a virtual team. Impressum Centre d'information, de conseil et de formation Professions de la coopération internationale Center for Information, Counselling and Training Professions relating to International Cooperation Authors Véronique Schoeffel, cinfo and Phyllis Thompson, consultant Graphic medialink Zürich © cinfo 11/2007 Rue Centrale 121 Case postale CH-2500 Bienne 7 Tél. +41 32 365 80 02 Fax +41 32 365 80 59 info@cinfo.ch www.cinfo.ch 20