Developments in Environmental Health

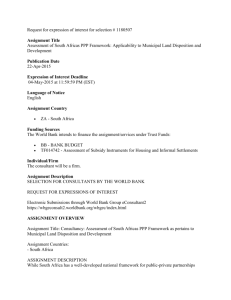

advertisement

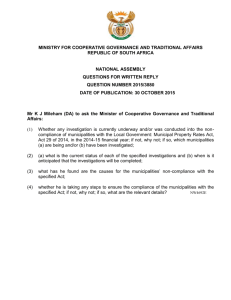

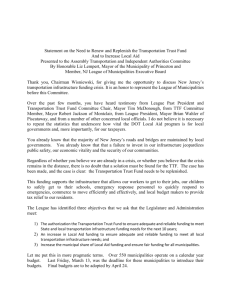

Developments in Environmental Health 10 Authors: Mike Agenbagi Thuthula Balfour-Kaipaii Abstract The importance of environmental health services in Primary Health Care and health services in general, will be highlighted in this chapter. Outlined will be the developments in environmental health services since 1978, including the impact of various new pieces of legislation, such as the National Health Act. Challenges with the devolution of environmental health services to metropolitan and district municipalities are explored. An assessment of some of the main environmental health components such as water, sanitation, food and malaria is provided. Furthermore, the critical issue of human resources for environmental health will be discussed, and recommendations are made for stronger support to be provided for the delivery of environmental health services, especially by district municipalities. i Ukhahlamba District Municipality ii Development Bank of Southern Africa 149 Introduction Environmental health is a critical and integral part of Primary It encompasses the assessment and control of those Health Care (PHC), as it contributes to the promotion of environmental factors that can potentially affect health”.3 wellness and prevention of disease, primarily by controlling environmental factors that negatively impact on health. Investments in the control of hazardous environmental factors, through environmental health, can lead to a reduction in the burden of disease. Globally, environmental health issues have evolved over time to encompass a more holistic approach, as reflected in the Report of the WHO Commission on Health and Environment.4 Sustainable development took centre stage and the effects of environmental degradation, due to human activity, were In 1999, the South African Health Review described South included on the agenda as important contributors to poor Africa as following a path addressing both ‘traditional’ and health. ‘modern’ environmental health issues, due to the history of the country that created two worlds.1 Since then, additional issues regarding sustainability of the modern environment, such as urbanisation, climate change and food insecurity have gained prominence. South Africa needs to move swiftly to address some of the outstanding ‘traditional’ environmental health issues, such as inappropriate and insufficient sanitation, water, waste management, housing and food quality. These issues may be neglected because of international interest, with developed countries pushing hard for action around long-term, emerging environmental issues (e.g. climate change) and these dominating global agendas. A key development since 2004 was the policy of devolution of most environmental health services to metropolitan and district municipalities. This was done in terms of the National Health Act (Act 61 of 2003), as part of a district health system that provides uniform, equitable and accessible health services.2 The legal, financial and staffing arrangements regarding the delivery by municipalities of these environmental health services, have gone through a still-incompleted and protracted period of transition. This Rapid urbanisation, climate change, globalisation, air pollution, poverty and inequity are now additional concerns for environmental health practitioners. Climate change is one of the major challenges to health due to its effects on access and quality of water supplies in the world, food insecurity resulting from a reduction in arable land, and its contribution to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, such as dengue fever and malaria. Globalisation is also adding to the rapid transmission of infectious diseases, such as influenza, around the world, and the potential transmission of diseases including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian flu. The link between environmental health and disease is well established, with ill-health being directly related to environmental hygiene and conversely, improvements to environmental hygiene contributing to better health.5 Medical therapy alone is not sustainable as a public health intervention, if environmental exposures that are associated with diseases are not also addressed and prevented. The burden of disease from environmental factors has been quantified by the WHO (see Box 1). process needs to be finalised to ensure that attention shifts to service delivery, and to the development of an equitable service based on the Alma Ata PHC principles of intersectoral collaboration, community participation, appropriate and Environmental health in South Africa before 1994 evidence-based technologies, access, affordability and equity Environmental health in South Africa was influenced by its to all. origins in England, in the early to middle nineteenth century. Since the early 1800s local government played a key role Background in the delivery of environmental health services in South What is environmental health? Before 1994, environmental health services were provided Environmental health is a diverse science, and its primary environmental health services were run by the homeland’s objective is to prevent disease and create health-supportive health department, with a few capable local municipalities environments. The World Health Organization (WHO) (e.g. Umtata Municipality in the Transkei homeland and perceives environmental health as addressing: “all the Mmabatho Municipality in the former Bophuthatswana physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a homeland) providing services in their area of jurisdiction. In person, and all the related factors impacting behaviours. the rest of South Africa, most environmental health services 150 Africa.7 by different administrative authorities.7 In each homeland, Developments in Environmental Health Box 1: Facts on disease and the environment Worldwide, 13 million deaths could be prevented every year by making our environment healthier. In children under the age of five, one third of all disease is caused by environmental factors such as unsafe water and air pollution. Every year, the lives of four million children under the age of five (mostly in developing countries) could be saved by preventing environmental risks such as unsafe water and air pollution. In developing countries, the main environmentally caused diseases are diarrhoeal disease, lower respiratory infections, unintentional injuries and malaria. Better environmental management could prevent 40% of deaths from malaria, 41% of deaths from lower respiratory infections and 94% of deaths from diarrhoeal disease; three of the world’s biggest childhood killers. In the least developed countries, one third of deaths and disease is a direct result of environmental causes. Environmental factors influence 85 out of 102 categories of diseases and injuries listed in the World Health Report. Source: World Health Organization, 2008.6 were provided by local municipalities. District municipalities, The then municipalities; namely metropolitan (category A), local called regional services councils, provided Constitution promulgated three categories of urban (category B) and district (category C). It gave municipalities communities in small towns, which could not afford their from categories A and C executive authority to deliver own environmental health services. Environmental health municipal health services, as defined by the Municipal practitioners from the Department of Health (DoH) rendered Structures Act and the National Health Act, promulgated environmental health services mainly to government in 2005. The National Health Act defines municipal health premises hazardous services as including a range of environmental health substances in urban and rural areas. These environmental services (see Box 2), but excludes port health services, health practitioners also provided general environmental control of hazardous substances and malaria control, which health services to towns where there were no local have become provincial functions.2,7,11 environmental (i.e. health services hospitals) and to rural monitored and government environmental health services available. 7 Box 2: The dominance of allopathic medicine in health service delivery impacted negatively on environmental health Municipal health services as defined by the National Health Act, 2003 Water quality monitoring practitioners were involved in other activities that were not Food control directly related to environmental health.1,7,8 Environmental Waste management health practitioners without transport became drivers for Health surveillance of premises PHC staff who had access to transport, but who did not Surveillance and prevention of communicable diseases, excluding immunisations of Vector control administration and technical services, neglecting their own Environmental pollution control Disposal of the dead Chemical safety services, to the extent that environmental health have drivers’ licenses.7,8 In other cases, environmental health practitioners became acting managers priority environmental health issues and only focusing on environmental health-related complaints for 10% of their time.7,9 Therefore, before 1994 environmental health services were fragmented and resources depended a Source: Republic of South Africa, 2003. 2 great deal on the resource levels of their administrative authority. Following the promulgation of the Municipal Systems Act, the Cabinet decided in October 2002, that municipal Developments in environmental health services after 1994 The legal framework for the establishment of environmental health services is rooted in the Constitution of the Republic health services would be defined as including a range of environmental health services. In May 2005, the National Health Act came into force and the responsibility for delivering municipal health services was thus formally left to metropolitan and district municipalities. of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996), the Municipal Structures The Cabinet decision and the promulgation of the Act (Act 117 of 1998) and the National Health Act. National Health Act did not have a major impact on 2,10,11 151 10 metropolitan already have pollution control functions.10,16,17 The various were powers, functions and responsibilities for the different mostly well resourced entities. For district municipalities, categories of local government have been determined. the implementation of the decision was fraught with However, there is still uncertainty with regard to some challenges, as these were newly established entities, with environmental health services activities that are divided little revenue generating powers, and were lacking in staff between local and district municipalities. This should be to oversee the process. Progress at this level was thus slow, viewed against the legislative backdrop that has given as it was also seen as an unfunded mandate.12 In 2006, the function for rendering municipal health services the National Treasury provided limited financial resources exclusively to metropolitan and district municipalities for environmental health services, as part of the equitable (see Box 3).2,10,11,16 Most problems with powers and share funding process (basic services component) to district functions between local and district municipalities are municipalities.12,13 The High Court of South Africa, on 10 being sorted out through consultation. Yet the split in April 2008, made a ruling regarding the interpretation of the provision of environmental health services is regrettable, definition for municipal health services, as stipulated in the as it makes planning for the services unnecessarily National Health Act, to embrace PHC, which was rendered complex. providing municipalities, environmental as health these were services, and by municipalities before the Act was enacted.14 This has far reaching implications for municipalities and creates Legal compliance District municipalities have to comply with different further challenges to district municipalities with regard to legislation, which addresses a vast array of issues to the availability of resources, as well as organisational and administrative arrangements. facilitate appropriate service delivery. The Municipal A number of studies have shown that the devolution of 77 and 78, that all municipalities should carry out municipal health services has been uneven; while some investigations (so called section 78 investigations) into provinces such as the Eastern Cape, the Free State and the their current and future capacity, when receiving a Western Cape were doing well, others were struggling. new municipal service or when a municipal service is By February 2007, two thirds of the district municipalities extended significantly.18 The metropolitan and district provided municipal health services, with the other third of municipalities should also be statutorily authorised by local municipalities (category B) still playing a significant the Ministry of Health under the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics role in rendering environmental health services.12 There were and Disinfectants Act (Act 54 of 1972) to enforce this signs of progress, as municipal health services were fairly Act.19 Systems Act (Act 32 of 2000) requires in sections 76, well integrated into municipal planning processes (especially However, long-term processes). Furthermore, resources for services a study by the Development Bank of Southern Africa showed that the section 78 were deemed to have improved at a macro level (i.e. national requirement was not adhered to by 40% of district and provincial) since devolution of service, but at micro municipalities. Additionally, nearly 60% of district level (i.e. metropolitan and district municipal) significant differences continued to occur.7,12 municipalities had not been authorised by the Ministry Studies also show that most of the key national and and Disinfectants Act) by September 2007, to enforce provincial role players, such as the South African Local the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act in their Government Association (SALGA), the national Department respective areas of jurisdiction, to control food quality of Health (NDoH) and the Department of Provincial and issues.7,12,19 Opportunities for improving the quality of Local Government (DPLG), designated to lead the devolution municipal health services rendered were thus missed of municipal health services, played a very limited role in as section 78 investigations gauge the capacity of the giving support and direction to metropolitan and district municipality to render any municipal service. of Health (section 23(1) of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics municipalities.12,15 Staffing levels The following are key challenges for district municipalities Environmental health staffing levels have decreased in implementing municipal health services. in a number of provinces, following the devolution Overlaps and conflict in the allocation of powers of and functions municipalities.12,20 Transfer of environmental health health services to district control, staff from most provincial health departments and where local and district municipalities, as well as the some local municipalities, has yet to take place.12,15,20 Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism The reason for this is due to the uncertainty around This 152 environmental is well illustrated with pollution Developments in Environmental Health Box 3: Illustration of overlaps in powers and functions Air pollution can be categorised into ambient and indoor air pollution. Each requires specific interventions from a variety of role players at different levels. Ambient air pollution control is mainly the responsibility of the Department of Environment Affairs and Tourism and through the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act (Act 39 of 2004) is enforced by national and provincial Air Quality Officers. In section 14(3) of the same Act each municipality is expected to designate an Air Quality Officer to coordinate air quality management within the respective municipal area. Metropolitan and district municipalities are responsible for implementing the atmospheric emission licensing system by issuing atmospheric emission licenses in their respective areas, as required by section 36(1) of the National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act. At the same time, for metropolitan and district municipalities, environmental pollution control is a municipal health service function, legislated by the National Health Act that addresses air, water and land pollution. As part of their powers and functions under section 83(1) of the Municipal Structures Act, local municipalities are responsible for air pollution control in their respective areas. However, the Municipal Demarcation Board of South Africa interprets district municipality’s powers and functions for municipal health services to include air quality control in their respective areas. These examples show how legislation leads to confusion around the exact roles of each entity regarding ambient and indoor air pollution control. Source: Compiled by the authors, originating from different documents.10,11,17 responsibility for the provision of the service. This has control are relatively well established throughout the led to the loss of many practitioners, legal challenges country. An active Inter-provincial Port Health Committee to the transfer of staff from local municipalities, local coordinates activities from the national level. Part of municipalities keeping staff for their own services the success can be attributed to the fact that powers and and municipalities freezing posts.7,12,20,21 The ability to functions are clearly defined and some of these services recruit more staff by district municipalities will largely were already being rendered by provinces. depend on the resources available to each municipality, including funding located within the provincial departments of health that could be transferred. As can be observed, a framework has been put in place for the delivery of municipal health services.2,7,8,10-13,16,18,20,22-24 Although not perfect, there is scope for improvement, if Funding levels there are concerted efforts and coordination by all relevant Funding for municipal health services was a concern stakeholders in environmental health. These include the in 2002.21 This was however partly addressed by the NDoH, the DPLG, SALGA, the South African Institute of National Treasury. Environmental Health (SAIEH), municipalities and tertiary 12,13 According to the Division of Revenue Act (Act 2 of 2006), environmental health institutions.7,8,12 services are basic services, which are funded through the local government equitable share, together with other basic services, including provision of water, basic sanitation, refuse removal and electricity supply.13 The continuing concern is that the amount of the equitable Review of main environmental health components share allocated for this is inadequate, as it was set at Developments in a number of specific environmental health R12 per household per annum (R3.25 per capita) in components will be reviewed, including water and sanitation 2006 and R18 per household per annum in 2008. This as well as food and malaria control. Highlighted will be how allocation was made despite the DoH recommendation these services have evolved, as well as the successes and that R13 per capita should be spent on the service.13,20,22 challenges that have arisen. Despite this alleged inadequacy, not all district Water and sanitation municipalities had accessed, or planned to access the available National Treasury funding by February 2007.12 The provision of sufficient quantities of safe water, facilities A comprehensive costing of environmental health for the sanitary disposal of excreta and promotion of sound services is long overdue, as this will guide municipalities hygiene behaviours can lead to significant improvements in and National Treasury in budgeting sufficiently for the health. Over 9% of the global burden of disease could be service. prevented through better management of water, sanitation Environmental health functions provided by provincial health departments, including port health services and malaria and hygiene.25 Bartram also states that better management Personal communication, E Bonzet, Western Cape Department of Health, 7 August 2008. 153 10 of water, sanitation and hygiene, in turn, could lead to Initially government followed a developmental approach reductions of diarrhoeal disease incidence of between in the provision of sanitation services. In 2000, the NDoH 25 to 37%. envisaged water and sanitation services that involved 25 communities in the planning, design, financing and Water maintenance of services. They also defined competencies for Since 1994, South Africa has made major strides in increasing access to basic water to all communities in the country, and prioritised the areas with the greatest need. Access to ‘basic water infrastructure’ improved from a coverage of 59% in 1994 to 94% in March 2007.,26 Aggregated at a national level, much progress is being made in improving access to ‘basic water infrastructure’, but there are still localities with persisting low safe water coverage. An emerging issue for access to safe water, which is of direct relevance to environmental health practitioners, is the declining quality of water provided by municipalities.21,27 South Africa has always been renowned for high standards of water quality, but this is no longer the case.27,28 The quality of South Africa’s surface and ground water is declining, with chemical and biological contamination, as well as rising salinity as the major causes of this decline.29 Poor investments and maintenance of waste water, and effluent infrastructure has led to the illegal discharging of effluent with high faecal coliform loads into rivers and streams.30,31 In addition to the pollution of water sources, water treatment is also not up to standard. A study in 2004 showed that only 43% of municipalities adhere to drinking water quality standards.32 Although the monitoring of water quality is the responsibility of water service authorities and the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF), environmental health practitioners play a significant role in monitoring water quality as part of their mandate related to municipal health services delivery, with the aim of protecting the health of the population.2,16,24 Environmental health practitioners conduct tests on water quality at the point of use (i.e. the tap) and report back to the municipality, the provincial DoH, and to DWAF. Environmental health practitioners are also required to promote health and hygiene awareness, including hygiene around water issues.21 the involvement of environmental health practitioners. The developmental sanitation approach emphasises to the demand-driven, provision of community-led and participatory methods for the delivery of sanitation services. However, this developmental approach takes time, but the benefits outweigh the time taken to deliver services. The 2001 White Paper on Basic Household Sanitation advocated for: community participation in sanitation; provision of sanitation that was responsive to the demands of people; a strong emphasis on health and hygiene; and local government supporting households in improving their own sanitation.28 With local government taking over responsibility for provision of sanitation and its inclusion in basic services delivered by municipalities, there was a shift from the demand-driven approach to a more supply led approach. Pressure was exerted on municipalities to fasttrack the delivery of basic services, including sanitation. The developmental approach to the provision of sanitation was thus abandoned as municipalities were more concerned with meeting targets for infrastructure delivery.27 The institutional mechanisms outlined in the White Paper on Basic Household Sanitation regarding the provision of sanitation are very complex, with roles for DWAF, the NDoH, the Department of Housing and Public Works, as well as for municipalities. It was envisaged that, with the involvement of municipalities, environmental health practitioners would play a more significant role in sanitation advocacy and hygiene promotion, which are coordinated by the NDoH. Regrettably, these expectations came at a time when the restructuring of municipal health services was also taking place. There was also uncertainty about the future of these services, resulting in under-investment in the service by municipalities and no guidance and support from the NDoH, the DPLG, SALGA and National Treasury.7,12,21,27 Other challenges emerging from the sanitation programme Sanitation are inappropriate technology, design and management. There In 2008, on the occasion of the International Year of are cases, for example, where ventilated pit latrines (VIPs) Sanitation, the Director-General of the WHO was quoted as are full, but municipalities have inadequate knowledge or saying: “Lack of sanitation kills. It degrades health - especially equipment to empty these. This, coupled with contamination that of children - and undermines education. It affects whole of ground water through badly placed VIPs is posing a major communities but consistently those most severely affected health hazard.27 are the poor and disadvantaged”. 32 The Department of Water Affairs and Forestry describes ‘basic water infrastructure’ as availability of infrastructure, without taking into account quality considerations. 154 Improvements in the delivery of sanitation have been slower than that of water. The current situation, based on data from the 2007 Community Survey is presented in Figure 1. Developments in Environmental Health Although there is some overall improvement, in the areas Food control where sanitation is worst, there has been relatively little change in levels of sanitation. The map also shows areas that Food control is a mandatory regulatory activity of still have very high levels of ‘inadequate sanitation’. enforcement by national and local authorities to provide consumer protection, and to ensure that all foods are A 2006 survey found that hygiene awareness is low in South safe during production, handling, storage, processing and Africa, with almost half the population underestimating the distribution. It also ensures that foods are wholesome, that effectiveness of hand washing in preventing the spread of they are fit for human consumption, that they conform disease.34 The result of poor hygiene education is that South to quality and safety requirements, and are honestly and Africa experiences episodic outbreaks of diarrhoea, and in accurately labelled as prescribed by law.35 a number of cases, person-to-person transmission (rather than water being the main route of transmission).27,28,34 Through the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, the Directorate for Food Control at the NDoH is responsible Much progress has been made in the provision of for the safety of food for all South Africans. Enforcement infrastructure for both water and sanitation. However, what of the Act is at local level for foodstuffs manufactured and is lacking is a more developmental and sustainable approach, sold locally, and at provincial level for imported foodstuffs which integrates environmental health practitioners more covered by the provisions of the Act and the related integrally to ensure that hygiene education is a major part Regulations published by the Minister of Health.7,19,35 of water and sanitation programmes. Cholera, typhoid and diarrhoeal outbreaks in Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, Historically, most local authorities (local municipalities and the Eastern Cape and the North West provinces serve as a forerunners of district and metropolitan municipalities) reminder, that more still needs to be done in this area.21 were authorised to enforce the stipulations of the Figure 1: Percentage of households with inadequate sanitation, 2007 Percentage of households with inadequate sanitation, 2007 LIM341 LIM351 Gauteng enlarged LIM331 LIMDMA33 LIM362 LIM367 LIM364 JHB NCDMA08 EKU NW395 NW381 GT483 GT423 NC081 NCDMA45 NW382 NC451 NW393 NW394 NC452 NC453 NCDMA08 FS173 FS172 FS161 FS171 FS162 NCDMA07 NCDMA06 FS163 NC075 NC064 NC074 NC072 EC144 NC066 EC131 WCDMA05 EC101 NCDMA06 WC012 WCDMA01 ECDMA13 WC013 ECDMA10 WC022 WCDMA02 WC051 WC023 EC107 WC025 EC132 WC041 WC045 WC026 WC031 EC141 WC034 WC042 WC043 WCDMA04 WC044 WC048 WC047 WC032 WC033WCDMA03 EC109 EC153 EC155 EC154 EC157 EC135 less than 10% EC124 EC123 EC127 10.0 - 19.9% EC125 EC126 EC105 ECDMA10 EC106 NMA Sanitation (inadeq) no data EC121 EC122 EC102 EC108 EC137 ECDMA13 EC134 EC104 WC015 CPT WC024 EC136 EC103 WC052 KZN272KZNDMA27 KZN265 KZN273 KZN434KZN211 KZN433KZN435 KZN212 KZN213 KZN214KZN215 EC442 KZN216 EC151 EC152 EC138 EC128 WC053 WC014 EC142 EC143 EC133 WC011 KZN263 FS194 EC156 NC071 KZN272KZN271 KZN262 KZN253 EC441 NC073 NC065 KZN252 KZNDMA22 KZN221 KZN293KZN292 KZN222 KZNDMA43KZN224 KZN225 KZN432 ETH KZN431KZN227KZN226 NC077 NC076 WCDMA01 FS192 FSDMA19 FS191 NCDMA07 NCDMA08 NC062 FS181 NC091 NC078 NC084 FS195 KZN254 KZN241 KZNDMA27 KZN266 KZN242 KZN274KZN275 KZN232 KZN285 KZN233 KZN281 KZN244 KZN286 KZN283 KZNDMA23KZN235 KZN282 KZN234 KZN284 KZN245 KZN236 KZNDMA23 KZN294KZN291 KZN223 FS184 FS182 NC067 MP303 KZN261 FS201 FS183 NC093 NC092 NC082 NC061 MP304 FS205 FS193 NCDMA09 NC086 NC085 MP302 MP305 FS203 FS185 MP324 MP301 MP307 FS204 NC094 NC083 MP322 MP323 MP313 MP312 GT423 GT421GT422 MP306 NW404 NW396 MP321 LIM472 MP314 NW405GT483 NW402 NW403 NW392 MPDMA32 MP325 MP315 GT482 JHB EKU MP311 NW401 NW391 GT422 MP316 GT461 GT481GTDMA48 GT462 NW384 LIM475 LIM473 TSH NW374 NW383 GT421 NW371 NW372 NW373 LIM335 LIM471 LIM366 NW375 NW385 LIM334 LIM355 LIM474 LIM361 GT481 GTDMA48 LIM333 LIM354 LIM365 GT462 LIM332 LIM353 LIM352 GT461 TSH GT482 LIM342 LIM343 LIM344 Boundaries 20.0 - 39.9% Provincial 40.0 - 59.9% District Municipalities 60.0 - 79.9% Local Municipalities 80.0% and above Source: Statistics South Africa, 2007. 33 ‘inadequate sanitation’ includes: no toilet, bucket toilets or pit latrines without ventilation. 155 10 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, but since Johns on the east coast in 1927, and as far as Gauteng in 1 July 2004 this responsibility was shifted to district the early 1930s.37,38 During bad years, these epidemics municipalities and metros.7,23 The activities of district resulted in up to 20 000 deaths in a single season.39 Residual municipalities and metros regarding food hygiene control spraying with insecticides (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane include: evaluation of food premises and sampling of (DDT) and later pyrethroids) and surveillance were the main foodstuffs; health education of food processors, handlers control interventions introduced in 1946. These interventions and prospective reduced malaria to low levels associated with seasonal entrepreneurs on requirements relating to food premises; focal outbreaks, following favourable climatic conditions and the safe handling of food and controlling illegally and the movements of infected migrants.40 Indoor residual imported foodstuffs offered for sale. spraying with DDT eliminated malaria from large areas of consumers; advising existing and 7,23,35,36 Outstanding issues regarding food control are related to the authorisation of municipalities and environmental health practitioners, under the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act and the National Health Act. Authorisations for local authorities, that existed prior to 2004, should be repealed by the Minister of Health in terms of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act. They should also be replaced by authorisations of the current metro and district municipalities.7,23,35 A study conducted by Agenbag in September 2007, showed that all metros were authorised, while 58.7% of district municipalities had not been authorised in accordance with section 23(1) of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act.7 This does not, however, mean that none of the other district municipalities had applied to the Minister of Health, but rather that some applications still needed to be processed by offices of the relevant provincial health departments. It is also the requirement, under the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, that there should be authorised officers who are mainly environmental health practitioners. The same study by Agenbag found that 64% of municipalities indicated that functional environmental health practitioners were authorised by the municipalities.7 A similar situation pertains to authorisations under the National Health Act. Two studies, one in 2006 and the other in 2007, revealed that only a quarter of the municipalities could confirm that their environmental health practitioners were authorised under the National Health Act.7,12,15 the country and reduced it to low levels in three provinces, such as eastern parts of Limpopo and Mpumalanga and the north eastern parts of KwaZulu-Natal, where it continues to occur. Occasionally, small malaria outbreaks develop in the Northern Cape and North West provinces. During these mentioned interventions, eliminated were the Anopheles funestus mosquito and greatly reduced was the density and distribution of Anopheles arabiensis, which is the main vector of malaria in the country. Annual reported malaria cases varied between 2 000 and 13 000 during the 1975 to 1995 period. However, reported infections increased significantly to a peak of 64 222 cases and 458 deaths in 2000. These increases have been attributed to climatic conditions, as well as resistance to the parasite drug and insecticide. There has been a sustained decrease in the number of nationally reported malaria cases and deaths, between 2001 and 2007. This success is a result of a combination of effective vector control, good case management and sustained political and financial support. Sustained control has been achieved through the ongoing strengthening of health systems, with strong monitoring capabilities and evaluating results. This has ensured that malaria mortality and morbidity stay low. With control at the current levels, within the borders of South Africa, it might now be feasible to achieve malaria elimination by reducing malaria transmission to zero.41 Environmental management played an important role during the eradication phase historically. This application remains under-utilised today and needs to be further explored. Food safety is receiving much attention worldwide, as consumers become more educated and conscious about the subject. It will become even more important as South Africa prepares to host the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and municipalities will need to ensure that all their authorisations, as well as those of their staff are in place. Human resources in environmental health Environmental health services are service delivery orientated, and are therefore mainly dependent on human resources for effective delivery. In 1999, the NDoH adjusted Malaria control the national norm away from the WHO norm of, one environmental health practitioner per 10 000 population Large parts of South Africa were historically affected by for developing countries, to one environmental health malaria, with epidemics spreading as far south as Port St practitioner per 15 000 population. This led to an apparent 156 Developments in Environmental Health improvement in the environmental health practitioner implementation of municipal health services at district to population ratio from a national perspective, because and metropolitan levels.7 The placing of environmental the shortfall of environmental health practitioners was health less.7,20,21 planning. This planning includes budgets and resources, The Western Cape, with an average of just over 13 600 population per functional environmental health practitioner, is the only province achieving the national coverage goal, while the Eastern Cape has over the past few years moved closer to the national norm, with an practitioners in municipalities requires more such as equipment, transport and offices, which need to be made available at a municipal level. Conclusion average of 22 479 population per functional environmental Environmental health services are at the core of PHC services health practitioner (see Figure 2). National environmental and the prevention of disease. Major health benefits are health practitioner to population figures normally include possible when these services are running well. 7 environmental health practitioners, such as those at management level in municipalities, who fill environmental health practitioner posts, but are utilised in areas not related to environmental / municipal health services. These national environmental health practitioner to population figures, also include the ‘community service year’ of environmental health practitioners, who are contractually appointed by provincial departments of health only for a period of a year.7,9,20,22 to district municipalities arose due to a lack of strong leadership, support and guidance to district municipalities, many of which were grappling with the provision of several other new services when they were required to take on this function. This led to the uneven devolution of the service as local leadership and resources determined how much support was provided to the establishment of environmental Figure 2: Comparison of functional environmental health practitioners (EHP) per population in South Africa, 2006/07 health services. This is likely to impact on the future equitable provision of the service. There are many lessons to be learnt from municipalities who 60 000 Community members per EHP Current problems regarding the devolution of the service managed this process well; lessons which should be shared with those who are struggling. Hence, a need exists for 50 000 relevant role players to assist in documenting and sharing 40 000 such lessons. 30 000 The restructuring of environmental health services into municipal health services, mostly provided by metropolitan and district municipalities, will improve coordination of 20 000 the service and will make it possible to provide it in a more equitable manner to all localities. 10 000 0 EC FS GP Median population per EHP KZN LP MP NC NW WC National EHP per population norm (1:15 000) Source: Agenbag, 2008.7 Community health Recommendations The process of devolution and consolidation of municipal service for environmental health practitioners was initiated in 2003, with 206 environmental health officers participating in the programme in 2006.42 Provincial health departments have benefited most as placing of new environmental health practitioners was not a problem. The Eastern Cape DoH’s strategy to absorb health services needs to be finalised speedily, through more support and leadership from the NDoH, provincial and local governments, as well as from other key stakeholders such as SALGA and SAIEH. More coordination and monitoring with clear targets and responsibilities between these bodies will fast track the establishment of the service. environmental health practitioners, who receive a bursary A need exists for the development of a section 78 from the department, has lead to the Eastern Cape investigation moving closer to the national norm of one environmental assessment) that can be used by municipalities that have health practitioner per 15 000 of the population.7 This not yet done their section 78 investigations, and such holds its own challenges when calculating the availability a guideline could be used as a monitoring tool for those of municipalities that have previously completed it. environmental health practitioner staff for the guideline (current and future capacity 157 10 A suggestion for such a guideline was tabled at the Eastern Cape municipal health summit in 2006.24,43 van Zyl and Chakane Sibaya, from Fezile Dabi District Municipality; Billy Barnes and Joof van der Merwe, from Municipalities need to plan for and support environmental Mangaung Municipality, for assisting with the provision health services, as with any other municipal services. The period of uncertainty around the devolution of the service is mostly over, and strengthening it through adequate resources and standardised systems is now required. Stronger leadership Environmental and Health stability Directorate in is the National required. This coordination body, which can give direction to, as well as evaluate and monitor the programme to influence national policy direction, resource allocation, facilitate role players to support systems development, and to standardise environmental health in South Africa. Arising from a Development Bank of Southern Africa dialogue, where the results from a national study were shared with key relevant role players such as the NDoH, the DPLG, National Treasury and municipalities a number of issues were raised. One of the most important was that municipal health services should be debated at a MINMEC (committee consisting of the National Ministers and Provincial Members of the Executive Councils) level and that the NDoH, supported by the DPLG, should facilitate such interaction to determine the way forward. critical issue requiring intervention is the establishment of a national environmental health forum. In the absence of support and national leadership for municipal health services, the environmental health fraternity, at local and provincial levels, has approached SALGA to establish a national municipal health services working group. This group, which was in principle approved by the national Executive Committee of SALGA towards the end of 2007, has not met as yet. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the following people: Philip Kruger, from the Department of Health and Social Development, Limpopo; Aaron Mabuza, from the Department of Health and Social Services, Mpumalanga; and Sakkie Hatting, from the Department of Health, KwaZulu-Natal, for their input on malaria control. Dries Pretorius and Penny Campbell, from the National Directorate: Food Control at the National Department of Health, for their input on food control. 158 of information. Jerry Chaka, from Ekuruleni Metropolitan Municipality and President of the South African Institute of Environmental Health; and Francois Nel, leadership will ensure the establishment of a proper Another Zies van Zyl, from Sedibeng District Municipality; Andre from Chris Hani District Municipality and National Secretary of the South African Institute of Environmental Health, for their guidance and advice. Developments in Environmental Health References 1 Mathee A, Swanepoel F, Swart A. Environmental health services. In: Crisp N, Ntuli A, editors. South African Health Review 1999. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 1999. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/chapter20_ 99.pdf 14 Republic of South Africa. In the matter between the Independent Municipal and Allied Workers Union (IMATU), the Minister of Health and Others. In the High Court of South Africa (Transvaal Provincial Division), Case Number: 3298/2006. 2008. 2 Republic of South Africa. National Health Act (Act 61 of 2003). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/acts/2003/a6103.pdf 15 Agenbag M. An analysis of progress made with the devolution of municipal health services in South Africa. Paper presented at the Seminar on Implementing Municipal Health Services, Pretoria, 2006 Jul 20-21. 3 World Health Organization. Environmental health [cited 2008 Jun 2]. URL: http://www.who.int/topics/environmental_health/en/ 16 4 World Health Organization. Our planet, our health. Report of WHO Commission on Health and Environment. Geneva: WHO; 1992. Municipal Demarcation Board. Local government powers and functions: Definitions, norms and standards. Pretoria: Municipal Demarcation Board; Updated Jun 2005. URL: http://www.demarcation.org.za/Documents/Reports/ Report%20_Defintions_2005.pdf 17 Republic of South Africa. National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act (Act 39 of 2004). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/acts/2004/a3904.pdf. 5 De Haan M, updated by Dennil K, Vasuthevan S. The Health of Southern Africa. 9th ed. Cape Town: Juta; 2005. 6 World Health Organization. 10 facts on preventing disease through healthy environments [cited 2008 Jun 2]. 2008. URL: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/ environmental_health/en/ 18 Republic of South Africa. Local Government: Municipal Systems Act (Act 32 of 2000). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/acts/2000/a3200.pdf 7 Agenbag M. The Management and Control of Milk Hygiene in the Informal Sector by Environmental Health Services in South Africa. Masters Thesis in Environmental Health at the Central University of Technology, Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2008. Unpublished. 19 Republic of South Africa. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act (Act 54 of 1972). URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/legislation/acts/1972/ act54.htm 20 8 Agenbag M, Gouws M. Redirecting the role of environmental health in South Africa. In: Paper presented at 8th World Congress on Environmental Health, Durban, 2004 Feb 23-27. Haynes RA. Monitoring the impact of municipal health services (MHS) policy implementation in South Africa. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2005. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/683 21 9 Atkinson D, Akharwaray N, Fouche N, Wellman G. Environmental health: Linking IDPs to municipal budgets. Task Team 6: Local Government Support and Learning Network (LOGOSUL). Northern Cape, Kimberley: Department of Local Government and Housing, 2002; p. 3-8. Eales K, Dau S, Phakati N. Environmental health. In: South African Health Review 2002. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2002. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/527 22 Republic of South Africa. Division of Revenue Bill (Bill 4 of 2008). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/bills/2008.pdf 23 Republic of South Africa. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act (Act 54 of 1972): Enforcement by Local Authorities. URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/legislation/acts/1972/ authorization.html 24 South African Local Government Association. Report on the Devolution and funding arrangements of municipal health services in the province of the Eastern Cape, 2007 Oct 12. URL: http://www.ukhahlamba.gov.za 25 Bartram J. Flowing away: water and health opportunities. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(1):1-2. URL: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/1/07049619.pdf 10 Republic of South Africa. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/ constitution/1996/a108-96.pdf 11 Republic of South Africa. Local Government: Municipal Structures Act (Act 117 of 1998). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/documents/acts/1998.pdf 12 Development Bank of Southern Africa. Delivery of municipal health services in district municipalities in South Africa: A census survey amongst district municipalities. Midrand: Development Bank of Southern Africa; 2007. 13 Republic of South Africa. Division of Revenue Act (Act 2 of 2006). URL: http://www.info.gov.za/gazette/acts/2006/a2-06.pdf 159 10 26 Annual Report of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry for 2006/07. Pretoria: Department of Water Affairs and Forestry; 2007. URL: http://www.dwaf.gov.za/Documents/ AnnualReports/2007.asp 27 Eales K. Lessons from South Africa’s basic sanitation programme. Sanitation Practitioner’s Seminar. Tanzania, 2007 Nov. 28 . Sanitation for a Healthy Nation: A summary of the White Paper on Basic Household Sanitation 2001. Pretoria: Department of Water Affairs and Forestry; 2001. URL: http://www.dwaf.gov.za/dir_ws/content/lids/PDF/ summary.pdf 29 Savage D, Eales K, Smith L. Securing South Africa’s water sector to support sustainable growth and development. 30 Van Vuuren L. Potential health time-bomb ticking in Free State. The Water Wheel; 2006 May/Jun. 31 Mackintosh GS, de Souza PF, Wensley A. Multidisciplinary considerations for satisfying water quality related services delivery requirements. A practical tool for municipal managers. Stellenbosch: Emanti Management; (undated). 32 World Health Organization. Director-General, On the Occasion of the International Year of Sanitation, 2008 [cited 2008 Jul 23]. URL: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/ hygiene/iys/about/en/ 33 Statistics South Africa. Community Survey 2007. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2007. URL: http://www.statssa.gov.za/Publications/CS2007Basic/ CS2007Basic.pdf 34 South African Press Association. Hand washing underestimated: Survey; 2006. URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/news/2006/nz0807.html 35 Department of Health. Directorate: Food Control. Information Document on the Role and Responsibility of the Public Health Sector in South Africa Regarding Food Safety Control –2000 Oct (Revised 2002 Sep). URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/department/dir_foodcontrf.html 36 Department of Health. Directorate: Food Control. Food control functions included under municipal health services to be rendered by metro and district municipalities as provided for in the National Health Act (Act 61 of 2003). URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/department/dir_foodcontrf.html 37 Le Seeur D, Sharp BL, Appelton C. Historical perspective of the malaria problem in Natal with emphasis on the period 1928-1932. S Afr J Sci. 1993;89:232-39. 38 Department of Public Health. Union of South Africa 1930 and 1934 Annual Reports. Available from the Malaria Institute at Tzaneen in the Limpopo Province. 39 Gear JHS. Malaria in South Africa: its history and present problems. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 1989;4:63-6. 160 40 Smith A, Hansford CF, Thomson JF. Malaria along the southern most fringe if its distribution in Africa: Epidemiology and control. Bull World Health Organ. 1977;55:95-103. 41 Department of Health. South Africa Roll Back Malaria Baseline Survey 2005. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2005. 42 Department of Health. Community service to improve access to quality health care to all South Africans. Department of Health statement, 2006 Jan 5 [cited 2008 Jun 2]. URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/search/index.html 43 South African Institute of Environmental Health. Eastern Cape Municipal Health Services Conference. East London Health Resource Centre, East London. 2006 Nov 28-30. URL: http://www.ukhahlamba.gov.za