IN THE CASE OF FLEXIBLE BUILDINGS

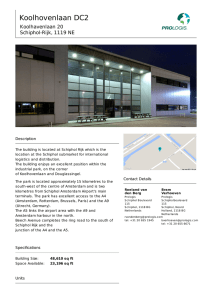

advertisement