GROSVENOR v. THE ADVOCATE CO. LTD. ET AL [COURT

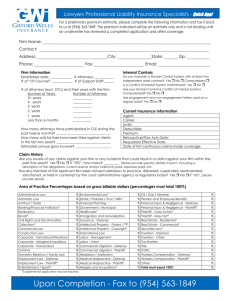

advertisement

GROSVENOR v. THE ADVOCATE CO. LTD. ET AL [COURT OF APPEAL - CIVIL APPEAL NO. 29 of 1991 (Williams, P., Smith and Moe, JJ.A.] September 6-7, 9-10, 13, 14, 1993; December 16, 1994, January 24, 1994] (1994) 30 Barb. L.R. 3 Labour law - Contract of service - Termination - Wrongful dismissal - Appellant employed with company - Ownership of company changed hands several times - During last change over appellant was retained on same conditions as previously on a three year contract which was to expire on January 31, 1987 - On February 23, 1987 appellant was informed by Board of Directors that employment would continue under same terms and conditions - Appellant reached retirementage but employment continued - In November 1987 Board set up committee to find replacementfor appellant - On April 18, 1988 appellant was informed that he was not eligible to receive directors' fees and on April 27, 1988, by letter, that his employment would end on July 31, 1988 and he would proceed on three months pre-retirement leave on August 1, 1988 – Whether appellant's contract breached and appellant wrongfully dismissed - Whether notice of six months lawfully terminated appellant's contract. Damages - Wrongful dismissal - Breach of contract - Application of Severance Payments Act,Cap. 355A, s. 45(1) - Quantum. Facts: The appellant was employed by the Advocate Company continuously for 44 years from1944 until in 1988 when his employment with the company came to an end. In 1966, the majority shareholder Overseas Newspapers Ltd. had sold its shareholding toThompson West Indies Holdings Ltd. which in 1984 sold the shares to the second respondent, McEnearney Alstons (Barbados) Ltd. The appellant was Managing Director in 1984 and on January 31, 1984 the Chairman of the Advocate wrote to him confirming his continued employment for a period of three years from the said date "on terms no less favourable than the terms of your present employment." A summary ofthe terms of employment was attached to the letter. A contributory pension scheme was incorporated into the provisions of the appellant's contract. A term of the plan indicated that the normal retirement for a member was age 60 and at the employer's discretion, age 65. Theappellant's contract was due to end on January 31, 1987 and he brought this to the attention of McEnearney's chairman beforehand. At a meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors held on February 23, 1987 after the appellantraised the question of his continued employment, he was informed by the Board that there was no intention to terminate his services and that [3] his employment would continue under the same terms and conditions as existed. At a Board meeting on November 2, 1987 a committee was set up to find a replacement for the appellant. At a meeting on April 18, 1988 the appellant was informed that he was not eligible to receive directors' fees. Four days later a new President was appointed and on April 27, 1988 theChairman of the Advocate wrote to the appellant informing him of his continued employment until July 31, 1988 and that he would proceed on 3 months pre-retirement leave on August 1, 1988. The appellant commenced proceedings alleging breach of contract or wrongful dismissal against the Advocate and for inducement of breach of contract against McEnearney. At first instance itwas held that there was a contract with the appellant for 3 years; that his employment wasterminated on July 31, 1988 without good cause, and that the Advocate was in breach of contract.It was also held that there was no direct evidence to support the appellant's case againstMcEnearney. On appeal by the appellant and cross appeal by the Advocate Held: (1) The effect of the Board's decision of February 23, 1987 was to renew the contractbetween the plaintiff and the Advocate for 3 years commencing on the expiration of the previouscontract on the same terms and conditions on which he had been engaged. When a suitablesuccessor for the appellant was found, the appellant had become surplus to the Advocate's needsand his departure from the Advocate had been rationalised by invoking the pension scheme as if he had recently reached age 60. The letter of April 27, 1988 was one of dismissal since there was animplied understanding that the Advocate would not terminate his employment as President beforethe expiration of his contract on January 31, 1990 and it was in breach of its undertaking when it did so on October 31, 1988; (2) the claim against McEnearney for wrongful interference with the appellant's contract failsbecause McEnearney was not interfering when its representative engineered the removal of the appellant's director's fees; (3) the appellant's appeal against the decision in favour of the Advocate is allowed and the advocate's cross-appeal is dismissed. The appellant's appeal against the decision in favour of McEnearney is dismissed; (4) damages in the sum of $467,689.00 awarded against the Advocate. Cases referred to: Barbados Plastics Ltd. v. Taylor (1981) 16 Barb. L.R. 79. Bray v. Ford [1895-99] All E.R. Rep. 1009. British Transport Commission v. Gourley [1956] A.C. 185. Clarke et al v. Nathu (1992) 27 Barb. L.R. 291. Correia's Jewellery Store Ltd. v. Forde (1992) 28 Barb. L.R. 180. Ogdens Ltd. v. Nelson, Same v. Telford [1904-7] All E.R. Rep. 1658. Rigby v. Ferodo Ltd. [1987] IRLR 516. Shindler v. Northern Raincoat Co. Ltd. [1960] 2 All E.R. 239. Southern Foundries (1926), Ltd., and Federated Foundries Ltd. v. Shirlaw [1940] 2 All E.R.445.[4] Stirling v. Maitland (1864) 5 B & S 841. Statutes referred to: Severance Payments Act, Cap. 355A, ss. 10, 11, 45(1). Severance Payments (Pensions) Regulations, 1972 as amended in 1976, Reg. 3(1), 4(1). Mr. D. Simmons, Q.C. in association with Mr. P. Cheltenham for the appellant. Mr. H.B. St. John, Q.C. in association with Mr. J. Hanschell for the respondent. WILLIAMS, P.: In 1944, Mr. Neville Grosvenor, the plaintiff-appellant ["the plaintiff"] entered into the employment of the Advocate Co. Ltd., the first defendant-appellant ["the Advocate"] as aproduction trainee and continued to work for the Advocate until 1988 when his employment with the company came to an end. He was, at that time, designated President and Publisher. Over the years the ownership of the Advocate changed hands on more than one occasion. In 1961the majority shareholder was Overseas Newspapers Ltd., but that company sold its shareholdingin 1966 to Thomson West Indies Holdings Ltd. ("Thomson"] which in 1984 sold the shares to the second defendant, McEnearney Alstons (Barbados) Ltd. ["McEnearney"]. The terms of Thomson's agreement with McEnearney were set out in a letter dated January 17,1984 from Thomson to McEnearney and accepted and endorsed by the latter on January 18, 1984. Paragraph 12 of the letter stated * "12. On the Closing Date the Company shall enter into an employment agreement with Neville Grosvenor in the form annexed hereto as Schedule "B". It is understood that it is your intention from and after the Closing Date, to cause the Company to continue to employ all other employees employed by the Company on the Closing Date on terms and conditions no lessfavourable than those under which they are employed on the Closing Date, including allexisting employee benefits." Mr. Neil Fitzwilliam who was at the time Chairman of the Advocate, wrote the following letter dated January 31, 1984 to the plaintiff who at that time was Managing Director - "Dear Mr. Grosvenor, This is to confirm our understanding that you are to continue to be employed as Managing Director of the Advocate Company Limited ["the Company"] for a period of three years from the date hereof on terms no less favourable than the terms of your present employment, a summary of which terms is attached hereto.[5] You shall, during the term of such employment, exercise and carry out all such duties and shall observe all such lawful directions as the Board of Directors or the Company or its authorised representatives may from time to time give you. During such term you shall faithfully, honestly and diligently serve as Managing Director of the Company, and, except during periods of illness or holidays, shall devote the whole of your working time, labour, skill and attention to such employment and shall use your best endeavours to promote the interests and welfare of the company. Would you kindly confirm this arrangement, by signing and returning to us the enclosed copy of this letter." There is an endorsement on the letter to the effect that the foregoing arrangement was confirmed by the plaintiff on the same date. The summary of terms attached to the letter was a reproduction of Schedule B referred to inparagraph 12 of the Thomson-McEnearney agreement. It reads - "The Advocate Company Limited SUMMARY OF PRESENT TERMS OF EMPLOYMENT OF NEVILLE GROSVENOR as Managing Director of THE ADVOCATE COMPANY LIMITED And Publisher of the Advocate Newspapers SALARY: $6,700 per month with annual increments averaging $600 per month ENTERTAINMENT ALLOWANCE: $900 per month with annual increases averaging$150 per month HOUSE ALLOWANCE: nil DIRECTOR'S FEES: $2,400 per annum EXECUTIVE COMPANY CAR: Fully serviced and maintained by the Company CONTRIBUTORY PENSION SCHEME: 7 1/2 per cent of salary paid by the Company and a similar amount personally [6] MEDICAL SCHEME: Nil GROUP LIFE ACCIDENT AND DISMEMBERMENT: Coverage of twice annual salary PROFIT SHARING: one tenth of the 10 per cent of operating profit before corporation tax allotted to staff VACATION: six [6] weeks annual leave per year with two first class passages for self and family and an additional allowance of two months salary every third year; SEVERANCE PAY: The existence of this employment contract shall in no way affect theseverance pay to which Mr. Grosvenor would otherwise be entitled under law should hisemployment terminate during or after the term of this contract. " It is not in contention that the reference in the above summary to the contributory pension scheme had the effect of incorporating its provisions in the plaintiff's contract. Section 4 of the Scheme, asamended, was as follows "The normal retirement date for a member shall be the anniversary of the effective date nearest the attainment of age 60 for males and females. At the discretion of the employer, a member may retire within the five years preceding or five years following his normal retirement date. The benefits payable to the member on such optional retirement date shall be adjusted to be actuarially equivalent to his accrued benefitsdue to commence at his normal retirement date. In the case of late retirement, no units of benefit shall accrue in respect of service beyond the member's normal retirement date." The plaintiff continued to serve as Managing Director pursuant to this contract and by letter datedDecember 8, 1986 brought to the attention of Mr. David McKenzie, McEnearney's Chairman, the act that his three-year contractual agreement was to expire on January 31, 1987. Mr. Mckenzie, together with Mr. Conrad O'Brien and Mr. Mark Conyers, had been made directors of the Advocate with effect from the completion of the sale by Thomson to McEnearney, filling some ofthe vacancies created by the resignation of the Thomson directors. [7] On February 23, 1987 at a meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors the plaintiff raised the question of his continued employment with the Advocate after the expiration of his contract on January 31, 1987. The following paragraphs are recorded in the minutes of the meeting - "The Managing Director drew to the attention of the Board that his three year contract with the Advocate Co. Ltd. had come to an end on the 31st January, 1987. He explained that the contract referred to was Appendix "B" of the sale agreement betweenThomson Newspapers and McEnearney Alstons (Barbados) Limited. He therefore wanted to be informed as to what was now his position with the Advocate Company Limited inrelation to the terms and conditions of his continued service. The Board informed the Managing Director that there was no intention to terminate his services and that his employment would continue under the same terms and conditions as existed under the sale agreement. " The plaintiff continued to serve as Managing Director. Some paragraphs of the minutes of a meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors held on April 13, 1987 are of significance. At page 4 it is recorded "Appendix B of Sale Agreement Mr. McKenzie stated that he did not recollect seeing a copy of Appendix "B" of the Sale Agreement and requested that the Managing Director forward a copy of that Appendix to him so that he could investigate the contents. The Board approved his request." At pages 5 and 6 "Appointment of Officers in Accordance with By Law No. 1 Mr. McKenzie informed the Board that in keeping with the policy of the Parent Board all Managing Directors or Chief Executive Officers of subsidiary companies of McEnearney Alstons (B'dos) Ltd. were now designated as President instead of Managing Director. It was resolved that persons listed in the first column here under be appointed to the office listed opposite their name. [8] Neville Grosvenor - President Hyacinth A. Lord - Secretary This was moved by Mr. Mark Conyers and seconded by Mr. Foster." At page 6 - Correspondence "The Secretary read the following correspondence to the board: (1) A letter from the Secretary of McEnearney Alstons (Barbados) Ltd. informing theAdvocate Co. Ltd. of a resolution of the parent board at a meeting held on April 8, 1987whereby Mr. John David S. Mckenzie was appointed the Company's representative at all general meetings of the Advocate Company Limited..." At a meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors on 2nd November 1987 the Board, on the recommendation of Mr. McKenzie, approved the immediate setting up of a committee of three directors to deal with, inter alia, the finding of a suitable person who would eventually be able to take over from Mr. Grosvenor and Mr. Best (Managing Editor) and an assessment of the management structure of the Company. The Committee members selected were Sir Neville Osborne, Chairman, Mr. Mckenzie and the plaintiff. The Advocate held its Eightieth Annual General Meeting on April 18, 1988 and the relevant partof the minutes is as follows: "At the request of the Chairman, Mr. David McKenzie moved and seconded the followingmotions 3 That the retiring directors Sir Neville Osborne, Mr. Percy Chenery, Mr. Mark Conyers, Mr. Paul Foster, Mr. Philip Goddard, Mr. Neville Grosvenor and Mr. David McKenzie be re-appointed for another year. In moving the re-appointment of the directors, Mr. McKenzie explained that in accordance with the policy of the parent Board, only non-executive directors were eligible for director'sfees. He then moved and seconded that the following fees be paid: Chairman $700 per month Non-Executive Directors $400 per month Mr. Neville Grosvenor as Chief Executive of the Advocate Company would not be eligible to receive director's fees if he accepted the appointment of being a director. Mr. Grosvenor informed the meeting [9] that he had nothing against the policy of the Parent Board butsince he was made a director of the Advocate Company Limited, he was always paiddirectors' fees, and in the existing terms of his employment, directors ' fees formed part of his remuneration. He asked leave of the meeting to seek advice on the decision to discontinue paying him directors' fees." In reply, Mr. McKenzie stated that Mr. Grosvenor's appointment as a director would be subject tothe conditions stated and requested Mr. Grosvenor to get back to him as soon as possible so thatthe matter of his appointment as a director could be settled. Four days later Mr. McKenzie wrote as follows to Mr. Patrick Hoyos "Dear Patrick, Further to our various conversations held to date and your letter of April 8th, 1988 let mesay or behalf of the directors of our parent company, the directors of the Advocate andmyself, how very happy and pleased we are to welcome you into our group as President and Publisher of the Advocate Company Limited. As was verbally agreed between us, it is understood that you will take up your appointment as from July 15th, 1988. Attached, please find a schedule confirming your position, salary, conditions of employment and perquisites as discussed and agreed between us earlier today. For our records it would be appreciated if you would sign and return the duplicate copy also attached. Once again I would like to say how happy I am to have you with us and I look forward to a long, happy and mutually beneficial association over the years. Yours very truly The Advocate Company Limited J.D.S. McKenzie Director" On April 27th 1988 the Chairman of the Advocate wrote to the plaintiff in these terms "Dear Neville, The Board of Directors have been reviewing the existing management arrangements of the Company and have given careful consideration to your contract of employment with the Company.[10] As you are aware, the Employees' Pension Plan provides inter alia, that the norma lretirement age shall be sixty years. You have now passed that age with both you and ourselves agreeing to your temporary continuance in office. The directors have come to the decision however, that your retirement should take place in accordance with your contractand the provisions of clause 4 of the Pension Plan and become effective on 31st October,1988. It is proposed that you continue in office until 31st July, 1988 and as from 1stAugust, 1988 go on three months pre-retirement leave on full basic pay until retirement date. The Directors further propose for your consideration, that you should act as consultant tothe Company for a period of six months immediately following retirement. The contract would provide for up to 200 hours of consultancy service at a fee of $2,000 per month. If you are wi11ing to enter into such a contract, further details could be discussed. The Directors would also be pleased to have you serve as a non-executive director of theCompany after the date of your retirement. With regard to the Company car which you now use, we would be pleased to arrange a special price should you be interested in taking it over. After you have had an opportunity to consider the foregoing, I would be glad if you would get in touch with me so that we can discuss and finalise the matter in more detail. Yours very truly The Advocate Company Limited Sir Neville Osborne Chairman" The plaintiff replied to the Chairman's letter two days later - "Dear Sir Neville, This is to acknowledge receipt of your letter of Wednesday, April 27 last in which you informed me that the Board of Directors of the Advocate Company Limited are reviewing the existing management arrangements of the Company and have given careful consideration to my contract of employment with the Company. I have read the Board's proposal for the termination of my services on the grounds of normal retirement as stated in the Employees" Pension Plan of July 1, 1973 and its further proposal to rehire me as a consultant with the [11] Company with non-executive director status. Before I can arrange to meet with you to discuss this proposal, I will be seeking legal advice on the matter following which I will inform you of an appropriate date. Yours very sincerely The Advocate Company Limited Neville S. Grosvenor President. c.c. Mr. David McKenzie Chairman, McEnearney Alstons [B'dos] Ltd." The following is an extract from the minutes of a meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors held on 5th May, 1988 "The Chairman informed the Board that the Sub-Committee had held several meetings tolook into the management of the Company, and had reached certain decisions. Mr. McKenzie stated that Mr. Grosvenor had now reached the age of to which was the retirement age under the Pension Plan of the Company and the Committee had decided tha this retirement should take place in accordance with his contract and the provisions of thePension Plan. Mr. McKenzie informed the Board that a letter had been written to Mr. Grosvenor to this effect and that the retirement should take effect at the end of October 1988 and that Mr.Grosvenor would go on three months pre-retirement leave at the end of July 1988. Hefurther told the Board that the letter contained: 1. An offer for consultancy after his retirement for a six month period for 200 hours ofconsultancy service at $2,000.00 per month. 2. An offer to have him serve as a non-executive director of the Company. 3. An offer to arrange a special price for the Company car which he now drives should hewish to take it over. He further explained to the Board that the Company would like to pay tribute to Mr.Grosvenor on his retirement and he proposed that a farewell dinner be held in his honourand that a suitable gift from the Company be presented 12] at the function. Mr. McKenzie further informed the Board that arrangements had been made with Mr.Patrick Hoyos and Mr. Tony Cumberbatch to come on as President/Publisher and Vice President, Marketing and Sales respectively ... The Board then agreed with the arrangements made by the Committee. It was noted that Messrs. Hoyos and Cumberbatch would assume duty as from July 15,1988. The Chairman said that he had received an acknowledgement of the letter written to Mr.Grosvenor, which indicated that he was seeking legal advice on the matter. Mr. Grosvenor informed the Board that he did not object to the parent Board's decision as he was getting older, however, he had worked with the Advocate Company Limited for 44 years, and under the Pension Scheme, he would only be receiving $1,602.27 per month. He further said that at the time of the sale of the Advocate Company Limited toMcEnearney Alstons [B'dos] Limited on January 16, 1984 the clause in his contract for severance pay was questioned by McEnearney Alstons [B'dos] Limited and it was explained by the Thomson representative. This explanation was accepted and signed the following day by both parties. As a result of this departure from the agreement, he was seeking legal advice on this compensation, and he would like to have the matter settled amicably, as he did not want to leave with any acrimony. The Board asked Mr. Grosvenor to get back to them as soon as possible after being advised, as an announcement had to be made when the matter was resolved." It is also recorded in the minutes of that meeting that the Board instructed the secretary that nofurther contributions should be made to the Pension Scheme in respect of the plaintiff with effectfrom July 1, 1988. The plaintiff's case, as pleaded The substance of the plaintiff's case as pleaded is that (1) it was an implied term in the plaintiff's contract of employment that the plaintiff would only be dismissed for good cause or upon reasonable [13] notice being given; (2) in pursuance of and in accordance with the terms and conditions express and implied inthe contract the plaintiff continued to work for the Advocate dutifully, faithfully andhonestly and in January, 1987 the contract expired but the Advocate's Board of Directors atits meeting of 23rd February, 1987 and as the Advocate's agents, agreed with the plaintiff that his employment would continue under the same terms and conditions as existed underthe Thomson-McEnearney agreement. In the premises, at all material times after 23rdFebruary, 1987 the plaintiff's contract of employment continued upon the same terms andconditions as had been the case prior to that date; (3) at the Advocate's 80th annual general meeting held on or about 18th April, 1988 Mr.David McKenzie, a director representing McEnearney's shareholders by proxy, and inducedby McEnearney, moved a resolution that only non-executive directors be eligible fordirectors' fees and that the remuneration therefor, be $400 per month; (4) by reason of the passing of that resolution, notwithstanding the plaintiff's objections, theAdvocate, in breach of the plaintiff's contract of employment and its terms, refused and/orneglected to pay the plaintiff director's fees and, in the premises, wrongfully terminated thecontract or constructively dismissed the plaintiff from his employment; (5) in further breach of his contract of employment, the Advocate, acting by its Chairman oragent Sir Neville Osborne, without reasonable notice [which the plaintiff says is one year]and/or without good cause wrongfully terminated the plaintiff's contract or wrongfullydismissed him therefrom on or about 27th April, 1988; (6) further, McEnearney, well knowing at all material times that the plaintiff and theAdvocate had entered into the aforesaid contract of employment, wrongfully and with intentto injure the plaintiff, authorised, procured and induced Mr. McKenzie, the holder of itsproxy, to cause the Advocate to break its contract with the plaintiff and to refuse to performor further perform it; (7) by reason of such procurement and inducement the Advocate did break and refuse toperform the contract. Particulars of constructive dismissal are pleaded at paragraph 14(a), (b) and (c) and particulars ofwrongful inducement at paragraph 16. The plaintiff's claim against the Advocate is for damages for breach of contract [14] and/orwrongful dismissal and against McEnearney for damages for inducement of breach of his contractwith the Advocate. He also claims interest and further relief. The Advocate's case as pleaded The Advocate admits that the plaintiff continued to work for it until January 1987 when hiscontract of employment expired and that its Board of Directors at its meeting of 23rd February,1987 agreed with the plaintiff that his employment would continue under the same terms andconditions as existed under the Thomson-McEnearney agreement but denies that it was an impliedterm of the contract that the plaintiff would only be dismissed for good cause or upon reasonablenotice. The Advocate goes on to say that continuation of the plaintiff's contract of employmentwas not on the agenda for the 23rd February meeting but was raised informally by the plaintiffhimself and it was at all material times the intention of the Board of Directors that the matterwould be formally considered at a later stage. The Advocate also says that it was the intention ofits Board of Directors that the plaintiff's employment would continue under the same terms andconditions on a temporary basis with no fixed period. It is further pleaded that the plaintiff attained the age of 60 years in May 1987 which was thenormal retirement age under its Employees' Pension Plan, that it had been agreed that the plaintiffwould continue in office temporarily notwithstanding that he had reached the age of retirement,that it was subsequently decided that his retirement should take place in accordance with hiscontract and with effect from 31st October, 1988, and that on 27th April, 1988 the Chairman ofits Board of Directors by letter proposed to the plaintiff that he continue in office until 31st July,1988 and as from 1st August, 1988 go on three months pre-retirement leave on full pay until theretirement date. The Advocate denies that it terminated the plaintiff's contract of employment asalleged or at all or that it wrongfully dismissed him as alleged or at all. Estoppel is also pleaded - that the plaintiff is estopped from alleging that he was wrongfullydismissed and that he was not retired in accordance with the provisions of his agreement with theAdvocate because he received $51,109.89 as a lump sum pension payment and $1,233.64 permonth as a pension from the Advocate. The Advocate counterclaims - (a) for the delivery up of its car which it had provided for the use of the plaintiff, or itsvalue: (b) for the sum of $177,009.30 which it claimed is the difference between the emolumentsand other benefits which the plaintiff had wrongfully and in breach of contract paid himselfand those that had been approved by its Board of Directors; and (c) damages for the breach by the plaintiff as a director of his duties and [15] obligations toit. Paragraphs 27 to 29 amplify the Advocate's claim under this head, viz: (i) at the time of the Board of Directors' meeting on 23rd February, 1987 and the 18th April,1988 the plaintiff acted both in the capacity of an employee and in the capacity of a directorbut the plaintiff's presence at those meetings was by virtue of his office as a director and notas an employee; (ii) the plaintiff as a director owed a duty of good faith to it and was under an obligation toexercise his powers properly for its benefits and not to fetter his discretion by placinghimself in a position where there was a conflict of interest between his duties and hispersonal interests; (iii) wrongfully and in breach of such duties and obligations the plaintiff acted in bad faithand against its interests at the directors' meetings and was motivated by his personalinterests which were in conflict with his duties as a director. Particulars of these allegationsare pleaded. McEnearney's case McEnearney denies that Mr. McKenzie was induced by it to move the resolution that onlynonexecutive directors of the Advocate be eligible for directors' fees and that the remunerationtherefor be the sum of $400.00 per month. It goes on to state that the resolution was moved byMr. McKenzie so that the Advocate's policy would be in accordance with the policy ofMcEnearney, the Advocate's parent company. The plaintiff's reply The plaintiff in his Reply contends that the Advocate arbitrarily or unilaterally ceasedcontributions to the Pension Plan as from 1st July, 1988 when he was 61 years oldnotwithstanding that the provisions of the Plan permit participants to retire at age 65. In thepremises, in so far as the provisions of the Plan were implied in the plaintiff's contract ofemployment, the Advocate was in breach of contract. In his Defence to the Advocate's Counterclaim he sets up - (a) with respect to the car, the Advocate's established policy and his reasonable andlegitimate expectations having regard to an established course of conduct or dealing by theAdvocate. He legitimately expected to be offered the opportunity to purchase the car at itsbook value in accordance with the Advocate's established policy and he was at all [16] timesready, willing and able to purchase the car at that value; (b) with respect to the overpayment of emoluments and other benefits, an estoppel byreason of matters which he particularised and of the conduct of the Advocate's Board; and (c) with respect to the claim for damages for breach of his duties and obligations as adirector, he says that at all times he exercised his powers and discharged his duties with theAdvocate's full knowledge, consent and approval. The Advocate caused and permitted himto hold the office of director and at the same time function as an employee and at no timedid he act in breach of his duties or in bad faith against the Advocate's interests nor was hemotivated by his personal interests or allowed such interests to conflict with his duties as adirector as alleged or at all. The judge's decision The learned judge, after reviewing and commenting on the evidence, concluded that the decisionof the Advocate Board as recorded in the minutes of 23rd February, 1987 was expressed in clearand unambiguous language and created a contract with the plaintiff for 3 years on the terms andconditions of Schedule B. He went on to hold that the plaintiff's employment was terminated on31st July, 1988 without good cause, by the Chairman's letter of 27th April, 1988 and that theAdvocate was in breach of its contract with the plaintiff. He held that, as damages for breach ofcontract, the plaintiff was entitled to receive the emoluments to which he would have been entitledduring the unexpired period of his 3 year contract. He awarded the plaintiff $267,714.00($14,873.00 x 18) in damages. The learned judge later stated that on the question of the notice given in the letter of the 27thApril, 1988, he would hold, if it were at all necessary for his decision, that having regard to all therelevant circumstances, reasonable notice required in this case would be 12 months. With respect to the plaintiff's case against McEnearney for inducing the Advocate to break itscontract with the plaintiff, the learned judge held that there was no direct evidence to support theplaintiff's claim as pleaded and the circumstantial evidence was such as would lead to a number ofreasonable inferences. The claim, he said, must fail. He awarded the Advocate $22,000 on its counterclaim in respect of the car. The counterclaim forover-payment of emoluments, and other benefits had been abandoned at the trial. The thirdcounterclaim failed, the judge holding that the evidence in the case, including the minutes of Boardand General Meetings did not disclose bad faith or unethical behaviour or a conflict of interests inthe performance by the plaintiff of his duties. Neither party has appealed against the decisions onthe counterclaims. [17] The Appeal The plaintiff in his appeal alleges error in law - (1) in the computation or assessment of his true measure of damages; (2) in construing his contract of employment in so far as it made provision in respect ofseverance pay; (3) in dismissing his claim against McEnearney for damages for the tort of inducing orprocuring a breach of his contract of employment with the Advocate; and (4) in failing to determine as was his duty, whether the appellant had in law beenconstructively dismissed by the Advocate. The Advocate's cross-appeal is against the findings of the learned judge - (l) that the decision of its Board of Directors as recorded in the minutes of 23rd February,1987 created a contract with the plaintiff for three years on the terms and conditions ofSchedule B; (2) that the plaintiff was wrongfully dismissed by it by the letter dated 27th April 1988; (3) that the date of termination of the plaintiff's employment was 31st July, 1988; (4) that the definition of "basic pay" in the Severance Payments Act may not be ascribed tothe words "basic pay" in the letter of 27th April, 1988; and (5) that it was in breach of its contract with the plaintiff. The Advocate also alleges that the judge erred in law and/or held against the weight of theevidence in the computation and/or assessment of the plaintiff's measure of damages because thesum of $267,741.00 awarded to him was erroneous and/or excessive and/or unjustified in thecircumstances. Was the decision of 23rd February 1987 a nullity? It is crucial to the resolution of the issues between the plaintiff and the Advocate to find out whatthe Board of the Advocate actually decided on 27th February, 1987 with respect to the plaintiff'scontinued employment. But before I can reach that [18] question I must consider and deal withMr. St. John's submission that the decision itself is flawed because the plaintiff's conduct in thematter fell far short of what the law required of him in the circumstances: it is said that it is anullity and cannot support the plaintiff's claim. The argument is that he was reaching the age of 60 and knew that was the normal retirement agefor members of the pension scheme and that continued employment after that age was in theAdvocate's discretion. Therefore, as President and Publisher and a director, he should have placedthat information before the Board so that the other directors would be aware of all the facts andcircumstances when exercising their discretion whether or not to extend the plaintiff's employmentage after 60. There is no record in the minutes that the plaintiff disclosed this information at themeeting. It is also said that the other directors were taken unawares when the item, which was noton the agenda, was unexpectedly raised towards the end of the meeting and that the plaintiffshould have withdrawn from the meeting when the question was considered and the decisiontaken. Palmer's Company Law, 24th Ed., 1987 sets out the principles on which reliance is placed (vol. 1,p. 943): "Like other fiduciaries directors are required not to put themselves in a position where thereis a conflict (actual or potential) between their personal interests and their duties to thecompany ... the position of a director, vis-a-vis the company, is that of an agent who maynot himself contract with his principal and ... is similar to that of a trustee who, however faira proposal may be, is not allowed to let the position arise where his interest and that of thetrust may conflict ... he is, like a trustee, disqualified from contracting with the company andfor a good reason: the company is entitled to the collective wisdom of its directors, and ifany director is interested in a contract, his interest may conflict with his duty, and the lawalways strives to prevent such a conflict from arising." The allegations made against the plaintiff are breach of his fiduciary relationship with theAdvocate, non-disclosure of material facts, conflict of interest, mala fides and the like, but, as Mr.Simmons for the plaintiff points out, thought these matters were raised on the pleadings in theform of a counterclaim (which was dismissed and against which there has been no appeal) theywere not pleaded against the plaintiff's assertion in paragraph 12 of the Amended Statement ofClaim that the Advocate's Board of Directors agreed with him that his employment wouldcontinue under the same terms and conditions as existed under the sale agreement. What ispleaded is that the matter was raised informally and the extension of his employment was on atemporary basis with no fixed period but there is no allegation that the decision is a nullity. In any case, whether pleaded or not, I do not think that the proposition advanced by Mr. St. Johncan succeed in the circumstances. The judge specifically accepted certain evidence about themeeting given by the plaintiff (p. 143 of the record): [19] "At the said meeting the plaintiff says he submitted a draft agreement for the Board'sapproval but it was returned to him unsigned. The plaintiff says, and I accept, that Mr.McKenzie told him it was not the policy of McEnearney Alstons to have written contractswith employees and that the age of retirement in McEnearney Alston's was 65 years. Theplaintiff was then 59 years old. He said he left the meeting with the understanding that hiscontract had been renewed for three years." It is reasonable to infer from Mr. McKenzie's telling the plaintiff that the age of retirement inMcEnearney was 65 years, that the Advocate's retirement age of 60 and the plaintiff's imminentattainment of that age were before the Board. So that although there is no record in the minutesthat the plaintiff disclosed his age or the relevant provision of the pension plan, the probability isthat those at the meeting knew not only that he was approaching the age of 60 but also that hiscontinued employment after that age, was a matter for them to decide. The picture that emerges from the evidence as a whole is that on 23rd February 1987 theAdvocate still needed the plaintiff's expertise and experience and the fact that he would soon reachthe age of 60 was of no consequence. New computerised machinery was going to be installed.The evidence shows that the machines arrived in September, 1987 and were installed betweenSeptember and November. The minutes of the Board meeting of 2nd October, 1987 reflect theimportance of the plaintiff to the Advocate during that period: "The Board complimented the President for the volume of the work he did, the long hourshe worked and all his efforts during the transition." And later: "Mr. McKenzie congratulated the President for the work he had done in the installation ofthe new equipment and said that without him he did not think it would have been done. TheBoard endorsed the sentiments expressed by Mr. McKenzie." It was at this meeting that the Board approved the setting up of a Committee, one of whosefunctions was to find a suitable person who would eventually be able to take over from theplaintiff. In my view, in assessing the plaintiff's conduct relative to this question his status as an executivedirector has to be borne ln mind. He was an employee, his contract had expired and he wasconcerned about his position. In my opinion, in deciding on the validity or otherwise of thedecision, the words of Lord Herschell in Bray v. Ford [1895-9] All E.R. Rep. 1009 at 1011 areapposite: "It is an inflexible rule of a Court of Equity that a person in a fiduciary position ... is not,unless otherwise provided, entitled to make a profit; he is [20] not allowed to put himself ina position where his interest and duty conflict. It does not appear to me that this rule is, ashas been said, founded upon principles of morality. I regard it rather as based on theconsideration that, human nature being what it is, there is danger, in such circumstances, ofthe person holding a fiduciary duty being swayed by interest rather than by duty, and thusprejudicing those whom he was bound to protect. It has, therefore, been deemed expedientto lay down this positive rule. But I am satisfied that it might be departed from in manycases, without any breach of morality, without any wrong being inflicted and without anyconsciousness of wrongdoing." The plaintiff's conduct did not cause the Advocate any prejudice. If the other directors had beentaken by surprise and needed time for reflection, their experience would have led them topostpone consideration of the question. The probability is that the Advocate could not afford tobe without the plaintiff at that time and there was no alternative but to continue to employ theplaintiff after he became 60. There was nothing ln the Pension Plan to preclude that and theevidence is that the normal retirement age in McEnearney and the other members of the groupwas 65. The decision is not a nullity. The decision Both sides led evidence as to what transpired at the meeting - the plaintiff in support of his caseand Sir Neville Osborne and Mr. McKenzie for the Advocate. According to the plaintiff, hehanded to the Chairman for the Board's approval a draft agreement similar to that which Mr.Fitzwilliam had signed in 1984, but it was returned to him unsigned. Mr. McKenzie told him - andthe judge accepted this - that it was not the policy of McEnearney to have written contracts withemployees and that the age of retirement in McEnearney was 65. He said he left the meeting withthe understanding that his contract had been renewed for 3 years. The Chairman and Mr. McKenzie do not dispute that the minute records the substance of what themeeting decided. But they both say that their understanding was that the plaintiff would continueon a temporary basis and the Board would, after informing itself and examining the terms ofAppendix B, determine what to do about the renewal of the contract. On this state of the evidence the judge sought the truth from the record of the meeting. There isnothing there about the employment being from month to month or on a temporary basis orpending the renewal of the contract. He went on to hold that the decision of the Board asrecorded in the minutes created a contract with the plaintiff for three years. It seems to me that the period over which it is agreed that contractual arrangements are to haveeffect is as much a term and condition of the contract as the salary or other matters that the partiesagree upon. The judge was entitled to regard the formal minute of the meeting as authoritative ofwhat was decided and [21] go on to hold that reference to the same terms and conditions asexisted under the Sale Agreement included a reference to the 3 year period over which the plaintiffwas engaged by virtue of Mr. Fitzwilliam's letter of 31st January. The judge's approach was notunreasonable since those who were at the meeting would have had ample opportunity to have theminute corrected if it did not reflect what had been decided. The judge's conclusion accorded with the plaintiff's account of what transpired at the meeting. Thedraft agreement is not in evidence but if it was similar to that which Mr. FitzWilliam had signed in1984. lt would have contained provision for a three year period, and Mr. McKenzie's telling theplaintiff that it was not McEnearney's policy to have written contracts with employees and thereturn of the**-***** draft to the plaintiff, would have induced the belief in the plaintiff thatcontinued employment for 3 years had been agreed. The judge's conclusion is also consistent with the plaintiff's subsequent conduct. The evidence isthat before the meeting he had been concerned about his future with the company. The judgeaccepted his evidence that in November 1986 he had informed Mr. McKenzie that his contractwas due to expire in 2 months' time. He wrote a letter to Mr. McKenzie dated 8th December 1986in which he mentioned that his 3 year contract was due to expire on 31st January 1987. It issignificant that he did not thereafter continue to pursue the question of his standing with thecompany. In my opinion the effect of the Board's decision of February 1987 was to renew the contractbetween the plaintiff and the Advocate for three years commencing on the expiration of theprevious contract on the terms and conditions on which he had been engaged under that contractby virtue of Mr. Fitzwilliam's letter, that letter having been issued by Mr. Fitzwilliam, theAdvocate's Chairman at the time, under the Thomson-McEnearney agreement. Constructive dismissal Continued employment under the same terms and conditions meant that the plaintiff had a claim tothe director's fees to which he was entitled under the contract that had expired. Under the Thomson-McEnearney agreement, the plaintiff was given $2,400 per annum asdirector's fees and his employment was to continue on terms not less favourable than the terms ofhis employment at that time. This in my view meant that his director's fees could be increased butnot withdrawn or reduced. When on the occasion of the Advocate's 80th Annual General Meeting on 18th April, 1988 Mr.McKenzie announced that only non-executive officers would be eligible for directors' fees and thatthe plaintiff, as the Advocate's chief executive would not be eligible to receive director s fees if heaccepted appointment as a director, he was signalling a breach of the plaintiff's contract ofemployment. In Rigby v. Ferodo Ltd. [1987] 1RLR (H.L.) their Lordships agreed with the speech of LordOliver of Aylmerton who said [at p. 516] - [22] "It is common ground that the unilateral imposition by an employer of a reduction in theagreed remuneration of an employee constitutes a fundamental and repudiatory breach ofthe contract of employment, which, if accepted by the employee, would terminate thecontract forthwith. " Lord Oliver later said (at p. 16) that he knew of no principle of law that any breach which theinnocent party is entitled to treat as repudiatory of the other party's obligations brings the contractto an end automatically. Grunfeld, The Law of Redundancy, Second Edition, at p. 113 deals with repudiation by theemployer of the contract of employment and "acceptance" by the employer of the repudiation - "Repudiation of the contract of employment by the employer may involve breach of anexpress term of the contract or of an implied term. For example, it may take the form of aunilateral reduction of wages, or of both status and wages, or of ordering the employee towork at another workplace without the contractual power so to transfer him, or ofinstructing the employee to undertake different work from that which he was engaged to do- such attempted unilateral variation will at common law be a repudiation of the contract ofemployment by the employer which, if "accepted" by the employee, constitutes dismissal bythe employer... As to `acceptance' by the employee of the repudiation, this may also occur in different ways.The employee may respond to the employer's repudiation by leaving the employmentwithout more; or he may enter upon a unilaterally varied job under protest until, within areasonable time, he obtains other employment...; or he may take the altered job for a fewweeks in order to mitigate his loss while looking for and finally obtaining alternative work;or he may undertake the new or altered work explicitly or impliedly on a trial basis. In anyof these alternative responses, it may be emphasised that, from the point of view ofconstituting a good `acceptance' of repudiation, it is immaterial whether the employee finallyleaves with notice or without notice. " In this case the plaintiff protested the decision and asked leave of the meeting to seek advice on it.Mr. McKenzie requested the plaintiff to get back to him as soon as possible so that the matter ofhis appointment as a director could be settled. The evidence is that the plaintiff's lawyer wrote to the Advocate through the Chairman. There isno evidence of the contents of the letter, but not long afterwards the plaintiff received theChairman's letter of 27th April proposing that he should continue in office until 31st July, 1988and go on three months pre-retirement leave with effect from 1st August, 1988. The plaintiff'stestimony is that he received his accustomed perquisites of office between 27th April and 31st July(p. 74 of the [23] record) and he did not leave the employ of the Company (p. 85). A reasonableinference is that the lawyer's letter led to a modified implementation of the Advocate's new policyon directors' fees in relation to the plaintiff and in the limited period it had by that time beendecided that he should remain in its employment. Mr. McKenzie's announcement of the new policy on directors' fees and its consequences for theplaintiff did not bring his contract to an end. Did the plaintiff accept the breach? Having regard towhat transpired subsequently it cannot be said that the plaintiff did anything that could beconstrued as an acceptance of the breach. In my view the evidence does not support a finding thatthe plaintiff was constructively dismissed. The letter of 27th April 1988 I turn now to the Chairman's letter to the plaintiff of 27th April, 1988 said by the Advocate to be aletter retiring the plaintiff at 60 pursuant to the provisions of the pension scheme. The notice givenby the letter was, it is said, generous and far more than was required in the circumstances. Mr. Simmons for the plaintiff does not agree. It is, he submits, no more than a letter of dismissalmasquerading as a letter retiring the plaintiff. What is the true purport and significance of the letter? First, it speaks of the plaintiff "now" havingreached the age of 60. This language corresponds to that used by Mr. McKenzie when he reportedto the Advocate's Board on 5th May, 1988: "Mr. McKenzie stated that Mr. Grosvenor had nowreached the age of 60." However, the plaintiff had reached that age about a year earlier. Second, it speaks of the Pension Plan's normal retirement age of 60 years without reference to thepossible retirement age of 65. The judge found that Mr. McKenzie had told the plaintiff at themeeting of February 23, 1987 that the age of retirement in McEnearney was 65. Third, it speaks of the plaintiff having passed age 60 with him and the Advocate agreeing to histemporary continuance in office. But the minutes of the February 23, 1987 meeting speak of theplaintiff's employment continuing "under the same terms and conditions as existed under the saleagreement." Mr. McKenzie's letter to Mr. Hoyos is significant in this context. It is dated April 22, 1988 andrefers to various conversations held between Mr. McKenzie and Mr. Hoyos and to Mr. Hoyos'letter of April 8, 1988. It then went on to welcome Mr. Hoyos into the group as President andPublisher of the Advocate. What appears to have taken place is that although a committee, which included the plaintiff, hadbeen set up on November 2, 1987 to deal with, among other things, the finding of a suitableperson "who would eventually be able to take over from the plaintiff", Mr. McKenzie had, withoutreference to the plaintiff, approached Mr. Hoyos as a possible replacement and had met withsuccess. The time taken to find a suitable successor for the plaintiff had not been as long asexpected, but once that person was found, the plaintiff had become surplus to the [24] Advocate'sneeds. Therefore, the decision was taken to terminate his employment by six months notice, threeto be spent in the office and three on leave. His departure from the Advocate scene wasrationalised by invoking the pension scheme as if he had recently reached age 60 and treating hisservice after that age as if his employment after January 31, 1987 had been continued from monthto month and without any fixed duration. When regard is had to all the circumstances, my opinion is that the letter of 27th April, 1988 wasone of dismissal and the issue which arises is whether the notice of six months given to theplaintiff lawfully terminated his contract of employment. Was the dismissal wrongful There had been no provision in the original contract whereby the Advocate could of its ownmotion terminate it by a period of notice and consequently there was no provision in the contractas renewed whereby it could be so terminated. The principle of law applicable was stated byCockburn, C.J. in Stirling v. Maitland (1864) 5 B. & S. 841 at 852: "if a party enters into an arrangement which can only take effect by the continuance of acertain existing state of circumstances, there is an implied engagement on his part that heshall do nothing of his own motion to put an end to that state of circumstances, under whichalone the arrangement can be operative." Reference was made to that principle in Ogdens Limited v. Nelson, Same v. Telford [1904-7] AllE.R. Rep. 1658 and Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd., and Federated Foundries Ltd., v. Shirlaw[1940] 2 All E.R. 445 and in Shindler v. Northern Raincoat Co., Ltd. [1960] 2 All E.R. 239Diplock, J., as he then was, applied the principle (at p. 224): "It does, however, seem to me that all five of their Lordships in the Southern Foundriescase were agreed on one principle of law which is vital to the defendant company'scontention in the present case." After reproducing the passage from Stirling v. Maitland quoted above, Diplock, J. continued: "Applying that respectable principle to the present case, there is an implied engagement onthe part of the defendant company that it will do nothing of its own motion to put an end tothe state of circumstances which enables the plaintiff to continue as managing director. Thatis to say, there is an implied understanding that it will not revoke his appointment as adirector, and will not resolve that his tenure of office be determined." [25] Applying the principle to this case, there was an implied engagement on the part of the Advocatethat it would do nothing of its own motion to put an end to the state of circumstances whichenabled the plaintiff to continue as President and Publisher. There was an implied understandingthat it would not terminate his appointment as President before the expiration of his contract on31st January, 1990 and it was in breach of its undertaking when it did so on 31st October, 1988. I will return to this and the quantum of damages payable by the Advocate to the plaintiff forwrongful dismissal after I have dealt with McEnearney's alleged tortious act in inducing theAdvocate to break its contract with the plaintiff. The tort of wrongful interference with contract Mr. McKenzie's participation in the Advocate's 80th Annual General Meeting on 18th April, 1988sprang from his appointment by McEnearney to represent it at all of the Advocate's generalmeetings. It is recorded in the minutes of the meeting of the Advocate's Board of Directors on13th April, 1987 that the Secretary had read a letter from McEnearney's secretary informing theAdvocate of a resolution of McEnearney's Board to that effect at a meeting held on 8th April,1987. Whether this tort is referred to as an inducement of breach of contract, wrongful interference withcontract or otherwise, an essential ingredient is interference by the defendant wrongdoer with theplaintiff's contract with a third person. I understand the law to be that if A without justificationknowingly and intentionally interferes with a contract which B has with C and causes damage toB, he commits an actionable wrong against B. But there mustbe an interference. The plaintiff's case that McEnearney interfered with his contract with the Advocate must in myview fail because McEnearney was not interfering when Mr. McKenzie as the representativeengineered the removal of his director's fees. McEnearney, as the Advocate's parent company, hada right to exercise its control in whatever way it saw fit. If the result was a breach of theAdvocate's contract with the plaintiff, that gave rise to a claim by the plaintiff against theAdvocate. But it could not give rise to any claim by the plaintiff against McEnearney with whomhe had no contractual relationship. To hold McEnearney liable in tort to the plaintiff in such circumstances would have far reachingsignificance for shareholders and indeed for company law. Is a shareholder, individual orcorporate, to be exposed to liability in tort whenever his, hers or its shares are voted in support ofa resolution that entails the breach of their company's contract with a third person? This is not in my opinion a question of McEnearney having to prove that there was justificationfor what it did. It is a case of McEnearney not having interfered with the Advocate's contract withthe plaintiff because, as a shareholder of the Advocate, the Advocate's business was its legitimatebusiness. The plaintiff's appeal against the judge's dismissal of its claim in tort against McEnearney must inmy view be dismissed.[26] Damages for wrongful dismissal Section 45(1) of the Severance Payments Act, Cap. 355A enacts - "45 (1) Notwithstanding any rule of law to the contrary, where, in any action brought by anemployee against an employer for breach of their contract of employment, the employeeclaims damages for wrongful dismissal, the Court shall, if (a) it finds that the employee was wrongfully dismissed; and (b) it is satisfied that, had the employee been dismissed by reason of redundancy or naturaldisaster, the employer would be liable to pay him a severance payment, assess those damages at an amount not less than such severance payment." The subsection makes special provision in respect of the assessment of damages for wrongfuldismissal in the circumstances to which it applies. For the provision to have effect the followingconditions must be satisfied: (1) there must be an action brought by an employee against an employer for breach of theircontract in which the employee claims damages for wrongful dismissal; (2) the Court must have found that the employee has been dismissed by reason ofredundancy or natural disaster, the employer would be liable to pay him a severancepayment. Once these three conditions are fulfilled the court must assess the damages payable at an amountnot less than the severance payment - notwithstanding any rule of assessment that says otherwise. In the present case conditions (1) and (2) are clearly satisfied. Condition (3) is also fulfilled. Infact, the Schedule B provisions and the summary of terms attached to Mr. FitzWilliam's letter of31st January, 1984 contemplated the possible application of statutory provisions on severancewhen it was stated - "The existence of this employment contract shall in no way affect the severance pay towhich Mr. Grosvenor would otherwise be entitled under law should his employmentterminate during or after the terms of this contract." This does not say that a severance payment would be payable to the plaintiff when or after hisemployment with the Advocate came to an end. It contemplates that such a payment couldbecome payable pursuant to the statute, depending on the [27] circumstances in which hisemployment came to an end. In this case no severance payment is payable, but, because theplaintiff was wrongfully dismissed, section 45(1) requires the computation to be made as if he isso entitled. Conditions (1) to (3) being fulfilled, an assessment of the damages payable to the plaintiff has tobe made pursuant to section 45(1). This involves two assessments, one at common law and the other as if the plaintiff had beensevered and whichever is greater is the amount payable under the subsection. At common law, damages in a case such as the present would be assessed by calculating theplaintiff's earnings had his contract run its full course and deducting therefrom what amount, ifany, he earned or should reasonably have earned in fulfillment of his duty to mitigate. The First Schedule to the statute applies for the purpose of calculating the severance payment thatthe plaintiff would have received had he been dismissed by reason of redundancy or naturaldisaster. Common law damages The learned judge found that on 31st July, 1988 the plaintiff was entitled to monthly emolumentsof $14,873 made up as follows: Salary: $10,000.00 Director's fees: 500.00 Entertainment allowance: 1,650.00 Car: 525.00 Telephone: 33 Petrol: 300.00 Air fares: 1,083.00 Accommodation: 555.00 Club allowances: 227.00 (Total): $14,873.00 No deduction was made of any amount which was or should reasonably have earned by theplaintiff in mitigation of damages and the plaintiff was awarded $267,714 calculated bymultiplying $14,873, his monthly emoluments, by 18 which was the number of months held by thejudge to be the unexpired portion of the contract. In this court, there was no criticism of, or submissions on, the figures found by the judge to be theplaintiff's monthly emoluments, no reference to, or submission on the effect, if any, of BritishTransport Commission v. Gourley [1956] A.C. 185 on the award. Holding the view as I do thatthe plaintiff's contract with the Advocate was terminated on 31st October, 1988, I would take amultiplier of 15 (i.e. November 1988 to January 1990) and calculate damages at common law at$223,095.[28] The severance payment Paragraph 3 of the Schedule applies for the purpose of determining the number of complete yearsof employment to be used in the calculation. The plaintiff had been employed by the Advocate for44 years but an upper limit of 33 complete years of employment is imposed. Four weeks' basic pay is allowed by paragraph 2 for each complete year of employment, "week'sbasic pay" being defined in paragraph 6 to mean, in relation to an employee like the plaintiff, histotal basic pay during the one hundred and four weeks immediately preceding the date on whichhe ceased to be employed, divided by one hundred and four. In the same paragraph "basic pay" isdefined for the purposes of the Schedule to mean - "the rate of pay of an employee, plus overtime payments, incentive or productivity paymentsand any other payments, allowances, or additions to the pay of an employee that are madeon a regular basis before any deductions are made: but does not include intermittent bonusesthat are not related directly to the productivity of the employee." Paragraph 4 of the Schedule provides that the preceding provisions of the Schedule are to haveeffect without prejudice to the operation of any regulations made under section 11 of the Actwhereby the amount of a severance payment, or part of a severance payment, may be reduced.The Severance Payments (Pensions) Regulations, 1972 (amended in 1976) were made under thatsection and a question raised during the addresses of counsel is whether any amount that would bepayable pursuant to the Schedule falls to be reduced pursuant to those regulations. I will consider first whether any reductions fall to be made under the Act. Section 11(1) provides: "The Minister may by regulations make provision for excluding the right to a severancepayment, or reducing the amount of any severance payment, in such cases as may beprescribed by the regulations, being cases in which an employee has (whether by virtue of anenactment or otherwise) a right or claim (whether legally enforceable or not) to a periodicalpayment or lump sum by way of pension, gratuity or superannuation allowance which is tobe paid by reference to his employment by a particular employer and is to be paid, or beginto be paid, at the time when he leaves that employment or within such period thereafter asmay be prescribed by those Regulations." Subsections (2) and (3) of section 11 need not be reproduced.Regulation 3(1) of the Regulationsprovides: "3(1) Subject to paragraphs (2) and (3), for the purposes of these regulations "pension"means a periodical payment or a lump sum by way of [29] a pension, gratuity orsuperannuation allowance as respects which the National Insurance Board is satisfied that - (a) it is to be paid in accordance with any scheme or arrangement having for its object orone of its objects to make provision in respect of persons serving in particular employmentsfor providing them with retirement benefits; and (b) except in the case of such lump sum which had been paid to the employee, the benefitsunder the scheme are secured by (i) an irrevocable trust which is subject to the laws of Barbados, or (ii) a contract of assurance or any annuity contract which is made with an insurancecompany registered under the Insurance Act; and (c) the scheme or arrangement is established by an enactment or other instrument having theforce of law in any part of the Commonwealth outside Barbados; and (d) the provisions made to enable benefits to be paid (taking into account any additionalresources which could and would be provided by the employer or any person connectedwith the employer, to meet any deficiency) are adequate to ensure payment in full of thebenefits." Paragraphs (2) and (3) are not pertinent. Regulation 4(1) provides: "4(1) These regulations apply in any case where an employee who is entitled, or but forthese Regulations would be entitled, to a severance payment from an employer, has a rightor claim to a pension for himself which (a) is to be paid by reference to the employee's last period of continuous employment withthat employer; (b) (i) if it is a lump sum, is to be paid, or (ii) if it is a periodical payment, is to begin to accrue, the time when the employee leaves the employment with that employer or within 90 weeksthereafter; and (c) in so far as it consists of periodical payments, satisfies the conditions specified inparagraph (2)." [30] Paragraph (2) sets out the conditions referred to at paragraph (1)(c) which are that the Boardmust be satisfied that, subject to certain specified exceptions, the pension is payable for life and isnot capable of being terminated or suspended. Regulation 5(1) provides that the employer of a pensioned employee (defined to mean anemployee who has a right or claim to a pension of a kind referred to in regulation 4) may, bynotice in writing given to that employee, claim to exclude the right of the employee to, or reducethe amount of, the severance payment to which the employee would otherwise be entitled underthe Act in accordance with, or to the extent permitted by, the First Schedule, and in such a casethe employee is not entitled to a severance payment, or, as the case may be, is entitled only to thereduced amount thereof. Paragraph (2) prescribes what the notice is to contain. In brief, these Regulations make provision in respect of certain pensions as defined in regulation 3and apply to the cases provided for in regulation 4. Regulation 5 enables an employer of anemployee who has a right or claim to a pension, as defined in Regulation 3, and of a kind referredto in Regulation 4, by notice in writing given to the employee, to claim to exclude the right of theemployee to, or reduce the amount of, the severance payment to which the employee wouldotherwise be entitled under the Act in accordance with, or to the extent provided by, the FirstSchedule. These Regulations, by themselves, cannot have the effect of reducing the amount of a severancepayment. There is no evidence that the Advocate made a claim under Regulation 5 or that a noticein writing was served pursuant to that regulation; there is no evidence that the National InsuranceBoard was approached to exercise its powers under Regulation 3; and, in any case the Boardcould not be satisfied in respect of Regulation 3(1)(c) because that provision requires that thescheme or arrangement must be established by an enactment or other instrument having the forceof law in any part of the Commonwealth outside Barbados. Clearly that is not the case with theAdvocate's pension scheme which was a private pension scheme arranged in Barbados with Life ofBarbados Ltd. Section 10 of the Act enacts as follows: "10(1) Where at any time there is in force an agreement between one or more employers ororganisations of employers and one or more trade unions representing employees, wherebyemployees to whom the agreement applied have a right in certain circumstances to paymentson the termination of their contracts of employment, and on the application of all the partiesto the agreements, the Minister having regard to the provisions of the agreement, is satisfiedthat section 3 should not apply to those employees, he may make an order under this sectionin respect of that --------agreement. (2) The Minister shall not make an order under this section in respect of an agreementunless the agreement indicates (in whatsoever terms) [31] the willingness of the parties to itto submit to a tribunal such questions as are mentioned in paragraph (b) of subsection (3). (3) Where an order under this section is in force in respect of an agreement (a) section 3 shall not have effect in relation to any employee who immediately before therelevant date is an employee to whom the agreement applies; and (b) section 38 shall have effect in relation to any question arising under the agreement as tothe right of an employee to a payment on the termination of his employment, or as to theamount of such a payment, as if the payment were a severance payment and the questionarose under this Part. (4) An order under this section may be revoked by a subsequent order thereunder, whetherin pursuance of an application made by all or any of the parties to the agreement in questionor without any such application." I reproduce this section to show that it cannot apply to the present case. It contemplates privatepension or severance payments arrangements between an employer or employers or anorganisation or organisations of employers and a union or unions representing employees. Itenables the Minister to make an order excluding the statutory severance payments on his beingsatisfied in terms of subsection (2). There is no evidence that the Advocate's pension scheme wasnegotiated with a union or that an order was made by a Minister under thesection. Section 12 makes provision for the modification of the provisions of the Act where a previousseverance payment has been made to an employee. It has no application to the present case. Under the Advocate's pension scheme the plaintiff received $51,109.89 as a lump sum paymentand draws a pension of $1,233.64 per month and the question is whether in calculating theseverance payment any reduction is to be made on account thereof. A conclusive answer in thenegative is provided by section 13 of the Act which enacts: "13. Except as provided for by regulations made under section 11 or by section 12, the rightof an employee to a severance payment under this Act shall not be excluded and the amountof a severance payment due to that employee shall not be reduced because of any right orclaim to any other payment due to the employee."[32] The computation The multiplier to be used in the calculation is 33, but ascertainment of the multiplicand is not asstraightforward. The learned judge did not address his mind to section 45(1) and consequently didnot make any finding as to what amount represented 4 weeks' basic pay. The question was raisedin this Court but not addressed in any detail. In the Amended Statement of Claim the plaintiffclaims $354,791.11 under this head but this figure was not broken down and is not even exactlydivisible by 33. In these circumstances, I would refer the matter to the parties to see whether agreement on thefigure can be reached failing which there will have to be an inquiry for the purpose of ascertainingthe amount to be allowed as 4 weeks' basic pay. Before closing I will refer to two cases on which submissions were made in the course ofargument: Barbados Plastics Ltd. v. Taylor [1981] 16 Barb. L.R. and Clarke et al v. Nathu(1992) 27 Barb. L.R. 291, both decisions of the Court of Appeal on appeal from magistrates. As was pointed out in Correia's Jewellery Store Ltd. v. Forde a decision of this court delivered onDecember 9, 1992, Barbados Plastics Ltd. v. Taylor (1981) 16 Barb. L.R. 79 was on the factscorrectly decided but statements made in the course of the judgment are misleading and should becorrected. It was said that whether a dismissal is wrong cannot depend on whether or not noticewas given and that where there is no good cause for the dismissal of an employee he can invokesection 45(1) and obtain the benefits which the Act provides for them. These statements are misleading because there are circumstances in which a servant's employmentcomes to an end which do not give rise to an action for wrongful dismissal. For instance, acontract may have run its course or may be determined in accordance with provisions agreed uponbetween the parties or otherwise in accordance with law. In such circumstances, the employeecannot claim to have been wrongfully dismissed and consequently there would be no basis for theapplication of the special assessment provisions of the subsection. Clarke et al v. Nathu (1992) 27 Barb. L.R. 291 was the case of a weekly-paid delivery driver whowas summarily dismissed after being employed for 15 months. This court held that in thosecircumstances section 45(1) could play no part in the assessment of damages for wrongful becauseshe did not have a sufficient number of complete years of employment to qualify for a severancepayment. Counsel draws attention to the words towards the end of the judgment: "In this case therespondent was a weekly worker and was entitled to a week's notice," and commented that theywere causing difficulty to some magistrates. However, the court was saying no more than that inthe circumstances of that case a week's notice was reasonable. It was not being suggested that aweek's notice would be reasonable in every case. What is reasonable notice depends on thecircumstances of the particular case.[33] Costs I would postpone the question of costs until there is an agreement or a determination on whatamount constitutes 4 weeks' basic pay and would adjourn this case for two weeks in order to seewhether the parties can reach agreement on that amount Decision on costs On December 16, 1993 a decision on the question of costs was reserved until there was agreementor determination on what amounts constitutes 4 weeks in order to see whether the parties couldreach agreement as to that amount. On resumption on January 5, 1994 Mr. Simmons for the plaintiff stated that two sums had beengiven to him by the other side, first $442,266.00 and, shortly before the resumption, $437,943.Clearly, these sums represented awards on the basis of 33 being the multiplier and it follows thatthe figure for 4 weeks' basic pay as given by the first defendant was $13,402.00 and later$13,271,00. Mr. Simmons stated that the plaintiff is willing to accept the smaller sum. An award of section 45damages on the basis of a multiplication of that sum by 33 (the number of complete years ofemployment) would be $437,943.00. Mr. St. John for the first defendant wishes now to argue for a reduction of the award on the basicof Gourley's case. Mr. Simmons opposes on the ground that it is too late to raise Gourley. Section 45 damages were in issue from the commencement of this case. In both the Statement ofClaim and the Amended Statement of Claim there was a claim for compensation in accordancewith the provisions of that section. Gourley was not argued before the trial judge and he made noreference to that case in his judgment. The first defendant in its grounds of appeal did not allegeany error in not taking Gourley's case into account. That case was not raised in argument duringthe many days that this case occupied the attention of this court and in the judgment read onDecember 16, 1993, it was specifically stated that there was no submission on the effect, if any,Gourley's case would have on the award. No reason has been put forward to show why leave should now be given to the first defendant toargue Gourley's case and leave to do so is refused. The plaintiff is entitled to section 45 damages against the first defendant in the sum of$437,943.00 and his appeal against the award of $267,714.00 by the trial judge is allowed withthe first defendant's cross appeal being dismissed. The plaintiff's appeal against the judge's decision in favour of the second defendant is dismissed. The plaintiff has never been paid for the months of September and October 1988 when he was stillin the employment of the first defendant. The trial judge (at p. 24 of his judgment) found that onJuly 31, 1988 the plaintiff was entitled to emoluments $14,873.00 per month. This figure wasnever in issue before this court and seems appropriate as the basis for the plaintiff's entitlement forthe months for [34] which he was not paid. On that basis judgment is given for the plaintiff againstthe first defendant for the sum of $29,746.00. Interest is granted on the total sum of $467,689.00 ($437,943 and $29,746) at the rate of 4% perannum from the date of the filing of the writ until today's date and hereafter at the rate of 8% perannum. The award of the trial judge (save that with respect to the motor car in which he gave judgementfor the first defendant against the plaintiff and against which there has been no appeal) is set asideand judgment is given in the terms stated above. The plaintiff is to have his costs against the first defendant on his appeal against the trial judge'saward and on the cross-appeal by the first defendant with a certificate for two attorneys-atlaw. The second defendant is to have its costs against the plaintiff on the plaintiff's appeal against thedismissal of his claim against the second defendant with a certificate for two attorneys-at-law. [35]

![[2012] NZEmpC 75 Fuqiang Yu v Xin Li and Symbol Spreading Ltd](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008200032_1-14a831fd0b1654b1f76517c466dafbe5-300x300.png)