Hadley v Baxendale - Carpe Diem

advertisement

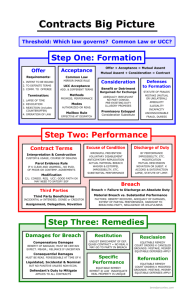

CQUniversity Division of Higher Education School of Business and Law LAWS11062 Contract Law B Topic 10 Remedies in common law and equity Term 2, 2014 Anthony Marinac © CQUniversity 2014 1 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................... 3 1.1 Objectives ....................................................................................... 4 1.2 Prescribed Readings ......................................................................4 1.3 Key Terms ...................................................................................... 5 2.0 Damages – the key remedy at common law .....................................6 2.1 Nature and objective of damages .................................................. 7 2.2 Quantum and assessment of damages ......................................... 8 2.3 Liquidated damages and penalties...............................................11 2.4 Expectation damages .................................................................. 13 2.5 Review questions......................................................................... 15 3.0 Causation – what must be compensated?....................................... 16 3.1 Remoteness and causation: Hadley v Baxendale ....................... 17 3.2 Mitigating measures ................................................................... 21 3.3 Contributory Negligence .............................................................24 3.4 Review questions ........................................................................26 4.0 Anticipatory breach ........................................................................ 27 5.0 Equitable remedies ........................................................................ 30 5.1 Specific performance ................................................................... 31 5.2 Injunction.................................................................................... 32 5.3 Rescission.................................................................................... 34 5.4 Restitution .................................................................................. 34 5.5 Review questions .........................................................................36 6.0 Review ............................................................................................. 37 7.0 Tutorial Problems .......................................................................... 38 8.0 Debrief ............................................................................................ 39 2 Topic 10 Remedies in Common Law and Equity 1.0 Introduction By now you can no doubt tell that we are quickly closing in upon the end of our study of contract law. We started out by learning how to form contracts, then we examined how to read and interpret contractual documents. At the start of this term we learned about circumstances which might vitiate a contract, and then last week we examined the circumstances in which a contract might be breached. This week we consider the consequences of such a breach, at common law and in equity. In other words, if the contract is not regulated by the Australian Consumer Law, what remedies will be available to the innocent party who successfully takes action in respect of contractual obligations which have not been fulfilled by the other party? We spent most of this week examining the fundamental common law remedy of damages. Damages represent money paid by the defaulting party to compensate the innocent party for the fact that the contractual obligations have not been met. This on its own is relatively simple. The concept of damages is complicated by the consideration of precisely what should be 3 compensated, and what the extent of that compensation should be. Finally this week we examine the more flexible range of remedies which are available in equity. Equity law recognizes that sometimes the most appropriate remedy will not be the payment of money; instead, equity provides for a range of alternative remedies. This week we will examine four: specific performance, injunction, rescission and restitution. 1.1 Objectives After studying Topic 10 you should be able to demonstrate: The operation of the common law remedy of damages, specifically including: o The objective of damages; o The calculation of the appropriate quantum of damages; and o The operation of the rule in Hadley v Baxendale; and The operation of the equitable remedies of rescission, restitution, specific performance and injunction. 1.2 Prescribed Readings Lindy Willmott, Sharon Christensen, Des Butler and Bill Dixon, Contract Law (Australia Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 2013) 4 Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre co v New Garage & Motor Co [1915] AC 79 Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 156 ER 145 Larking v Great Western (Nepean) Gravel (1940) 64 CLR 221 Lexmead v Lewis [1982] AC 225 Moses v MacFerlan (1760) 97 ER 676 Radford v De Froberville [1977] 1 WLR 1262 Shindler v Northern Raincoat [1960] 2 All ER 239 Turner v Bladin (1951) 82 CLR 463 Victoria Laundry v Newman Industries [1949] 2 KB 528 1.3 Key Terms Causation: Describes a logical link between some event and some outcome, where the event causes the outcome. Continuing breach: A continuing breach occurs in circumstances where the failure to complete contractual obligations causes continuing losses to the innocent party. Contributory negligence: Contributory negligence describes a circumstance in which the innocent party has somehow contributed to their own loss. Contributory negligence will usually reduce the amount of damages payable. Damages: An order by the court for the payment of money to compensate the innocent party for the losses which they have suffered as a result of the defaulting party’s failure to complete their contractual obligations. 5 Expectation damages: Expectation damages describe compensation which is paid not to compensate the innocent party for a harm they have suffered, but rather to compensate them for the gain which they might have expected to obtain under the contract. Injunction: An order by the court to refrain from or (more rarely) to undertake some action, not necessarily a contractual obligation. Liquidated damages: Where a contract specifies an amount of money to be paid in the case of default, the amount of money is referred to as liquidated damages. Penalty: Where liquidated damages do not represent a genuine and reasonable estimate of the damages likely to be suffered in the event of a breach, liquidated damages will be referred to as a penalty, and will often be unenforceable. Restitution: An equitable remedy whereby a party which has become unjustly enriched in the course of a contractual dispute is required to forego that unjust enrichment in favour of the innocent party. Specific performance: An equitable remedy whereby a party is required by the court to perform their contractual obligation. 2.0 Damages – the key remedy at common law I suspect most of us have a general idea of what damages are. In short, the court orders the party at fault to pay a sum of money to the plaintiff. The purpose of that sum of money is to compensate the plaintiff for the harm they have suffered as a result of the default. On its own, that sounds simple enough: 6 however once we start to unpack this definition, the concept of damages becomes surprisingly tricky. The first thing to understand about damages is that damages are the quintessential common law remedy. Do you remember that in Introduction to Law you learned about the separate development of the common law and the law of equity? One of the advantages which the law of equity had (at least as far as contract law went) was that it developed a range of remedies, whereas the common law courts were only able to award damages. So, let’s take a look at how damages work. 2.1 Nature and objective of damages The first thing to understand is that, in general, damages are intended as a form of compensation, not a form of punishment. The general objective of damages is to compensate the original party for the losses which they have suffered as a result of the other party’s failure to complete their obligations under the contract. It is not the objective to, for instance, impose a penalty in order to deter the individual, or others in society, from failing to meet their subsequent contractual obligations. The court does not look into the question of whether moral blame should be attached to the party which has failed to meet their contractual obligations. It follows, of course, that damages can only be awarded if a breach is established, and if the plaintiff is able to show a loss. The burden of proof for these things falls upon the plaintiff. The plaintiff must show that there was a breach at law, and the plaintiff must show what losses were suffered as a result of that breach. 7 2.2 Quantum and assessment of damages Once a cause of action has been established (in other words, once a breach has been shown), and once the issues of causation (see below) have been dealt with, the purpose of the court will be to impose damages which compensate the plaintiff for the harm suffered as a result of the breach. 2.2.1 Date of assessment The harm will usually be assessed as at the day of the breach itself. An authority for this is our old friend Commonwealth v Amann Aviation (1991) 174 CLR 64. As a result, in many cases, any harm suffered following the breach will not be compensable. The rationale for this is that once the breach has occurred, the innocent party will be able to look out for their own interests and prevent further losses. This rule is not, however, hard and fast. The courts are able to choose a different date of assessment if they consider that it would be unjust to assess damages as of the date of the breach. For instance, if the transaction was for the sale of goods, but there was no other ready supplier of those goods, it might not be possible for the innocent party to protect themselves from further losses by obtaining the goods elsewhere. Under those circumstances, the court might consider it appropriate to assess the losses at a date some time after the actual breach. For example, in the rather odd case of Radford v De Froberville [1977] 1 WLR 1262, De Froberville purchased a house adjoining the block of flats owned by Radford. As part of the purchase, she covenanted (i.e. promised) to erect a very substantial wall on the boundary between the properties. She failed to do so, and Radford sued for damages. De Froberville, however, argued that no damage had been suffered. The court found that 8 Radford should receive damages sufficient to cover the cost of building the wall himself. Let’s think about this. When did the breach occur? Effectively, the breach occurred when De Froberville failed to build the wall. Radford’s efforts to build the wall himself came afterwards. The cost of the building materials etc may have fluctuated in the meanwhile – however the court found that in these circumstances, the proper date of assessment related to when the new wall was built, not when the breach occurred. However, as a general rule, remember that the date of assessment of damages will be the date of the breach itself. And almost all of the time, this rule works out just fine. 2.2.2 Damages are “once and for all” When the court imposes damages, the court’s judgment is held to settle the matter finally and absolutely. Parties are not entitled to subsequently come back for more, even if it turns out that they later incur additional harm as a result of the breach (which they had perhaps not anticipated or known about at the time of their initial court action). However, there are a couple of exceptions. If there is more than one cause of action. OK, this isn’t really an exception, I guess. It makes sense that if there are two causes of action, then the resolution of the first cause of action doesn’t stop the plaintiff from proceeding with the second. If there is a continuing breach. Sometimes, a contract may be for a period of time. If a warranty in that contract is breached, there will be an entitlement to damages, but the contract will not be terminated. It will continue to run. What happens if the breach continues? For instance, what if the 9 contract is for the hire of a ship which is to be maintained in seaworthy condition by the owner? The ship becomes seaworthy, and the hirer sues, and receives damages. However the shipowner then takes no steps to rectify the breach. Can you see that this is a continuing breach? The same breach is continuing to do harm. In the alternative, let’s say the shipowner did return the ship to seaworthiness, but then it later became (again) unseaworthy. This would not be a continuing breach. Instead, the second breach would give rise to an entirely new cause of action. In Larking v Great Western (Nepean) Gravel (1940) 64 CLR 221, Larking gave the company the right to extract gravel from part of the Nepean river bed. As part of the deal, the company was to erect some fences and gates. They did not do so. The contract continued to run, and eventually came before the courts. One question was whether the breach was a once-andfor-all breach, or a continuing breach (since the defendant had continued to fail to erect the fences and gate). The court found that this was a once-and-for-all breach, not a continuing breach, and that the plaintiff had continued to accept royalties from the dredging after the breach had occurred, so the plaintiff had lost the opportunity to terminate the contract. As you can see, the distinction between one-off and continuing breaches can sometimes be complicated to make. 10 20240463 2.3 Liquidated damages and penalties Sometimes prudent parties will agree, in the contract itself, what damages should be paid in the event of specified breaches of the contract. Such damages are usually referred to as liquidated damages. A liquidated damages clause makes a great deal of sense for the parties, because it takes any potential calculation of damages out of the hands of the court, and puts it back in the hands of the parties. The contract – and the consequences of any breach of the contract – becomes a lot more predictable. Where parties have agreed to liquidated damages, the court will enforce the liquidated damages clause, and the parties will lose any right to common law damages arising from the breach. In other words, not only will liquidated damages be enforced, they will also cancel out any common law remedy. 11 However there are limits on the extent to which parties can liquidate damages. For a sum to qualify as liquidated damages, it must be a genuine predictive estimate of the likely loss. In other words, the amount of the liquidated damages must bear some reasonable relationship to the likely harm. If it does not – if the liquidated damages are obviously higher than the likely actual losses – then the liquidated damages will be regarded as a penalty. As we have already learned in this topic, the purpose of damages is to compensate, not to penalize. This principle continues into the field of liquidated damages. If a liquidated damages clause has the effect of penalizing the defaulter, of imposing consequences which quite obviously exceed the potential harm, then the liquidated damages clause will be void. It will still, under those circumstances, be open to the innocent party to seek common law damages. Let’s look at an example, which may help. In Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co v New Garage & Motor Co [1915] AC 79, Dunlop supplied tyres, tyre tubes and tyre covers to New Garage, which then sold them on to consumers. Part of the contract specified that there was a minimum price for each article, and that New Garage was not able to sell Dunlop’s products for less than that minimum price. The contract included a liquidated damages clause which imposed damages of five pounds per item sold below the minimum cost. Controlling for inflation and currency conversion, that amounts to approximately the equivalent of $900 Australian per unit. That’s a fair amount of money! New Garage, as you may have guessed, sold Dunlop products without adhering to the price-maintenance part of the contract. Dunlop sued to enforce the liquidated damages clause, and it 12 came before the courts. So, what do you say? Was this liquidated damages, or was it a penalty? The court found that this was liquidated damages, not a penalty. I have always found this a hard decision to support. To me, it seems like the damages really were exorbitant compared to the losses Dunlop might have suffered as a result of the challenge to their price-maintenance strategy. Some level of damages – sufficient to ensure the retailer would not engage in discounting – would seem to be appropriate, but the actual amount seems to me to have been a penalty. So, where is the boundary? As with so many other principles we have come across in our study of contract law, there really is no boundary. Whether an amount will be liquidated damages or a penalty really will depend upon the facts in an individual case. From our perspective, the test will always be whether the amount of damages prescribed in the liquidated damages clause is a genuine and reasonable estimate of the damages likely to be suffered in the event of a breach. 2.4 Expectation damages The final type of damages we need to consider is referred to as expectation damages. At the outset, we stated that the purpose of damages was to compensate the innocent party for the loss they suffered as a result of the breach. However, very few parties go into a contract without an expectation that they will be in some way better off at the end of the contract. Sometimes contracts are mere exchanges: I exchange $100 in cash for $100 worth of topsoil for my garden. However more often, contracts are entered into in the expectation of making a gain. As a result, the failure of one party to meet their obligations under the contract may not just cost the other party any expenses they 13 have incurred; they might also cost the other party the gain they might have expected to obtain. Under some circumstances, the innocent party will be able to obtain “expectation damages” to compensate them not only for the losses they have incurred, but also for the profits they will now never see. The classic example of this situation comes in the case C.Czarnikow v Koufos (1969) 1 AC 350. In this situation, Czarnikow chartered a ship owned by Koufos, to carry a load of sugar for sale to merchants in the Middle East. However the shipowners caused deviations to the ship’s route, with the result that the sugar arrived in its destination port nine days after it should have. Ordinarily, one might think this was not too much of a problem; the sugar could still be sold, and a profit realized. The shipowners acknowledged that they would be liable to pay interest on the value of the sugar for the nine days. So where’s the problem? Well, during those nine days, another boat load of sugar had arrived in the same port. The market was now oversupplied with sugar, and the price had therefore dropped. As a result, Czarnikow did not just want nine days’ interest – they wanted the difference between the price they actually obtained, and the price they would have obtained had the contract been completed in a timely manner. The court accepted this claim. Lord Reid set out the test, in his judgment, which has since been used in Australian cases: The crucial question is whether, on the information available to the defendant when the contract was made, he should, or the reasonable man in his position would, have realised that such loss was sufficiently likely to result from the breach of contract to make 14 it proper to hold that the loss flowed naturally from the breach or that loss of that kind should have been within his contemplation. So, if a reasonable person could foresee the loss of expectation at the time the contract was formed, the expectation loss will most likely be compensable. 2.5 Review questions Question 1 Under what circumstances are damages not assessed on a “once and for all” basis? a) In the event of an anticipatory breach; b) If the contract has been repudiated; c) If there is a continuing breach; d) If damages are liquidated. Answer: (c) Question 2 What is a penalty? a) A free kick, usually given for rough play or another breach of the rules; b) An enforcement measure between parties, intended to compel compliance with the contract; c) An enforceable undertaking between the parties; d) An unenforceable liquidated sum with no reasonable relationship to the harm caused. Answer: (d) 15 Question 3 Who bears the burden of proving both breach and harm? a) The promisor; b) The promisee; c) The plaintiff; d) The defendant. Answer: (c) 3.0 Causation – what must be compensated? To this point, we understand that damages must be paid, with the intention of restoring the innocent party to the position they might have been in, but for the breach: that is, to compensate them for actual losses they have suffered, and also potentially for the loss of expectations under the contract. As you might imagine, there will always be a temptation for the innocent party to “stretch” their claim; having established the breach, there may be a natural inclination to try to obtain the maximum possible damages as a result. In fact, many law firms now quite openly advertise on the basis of their ability to maximize payouts in all manner of legal matters. Consider this possibility: I have a contract with a furniture delivery company to deliver furniture which I have purchased, to my home, no later than 3:00 pm. I have told the company that it is imperative that I receive the goods by this time, as I have an appointment at 3:30 pm. I did not tell them that the appointment was for a job interview – that was none of their business. Time was the essence of the contract. 16 As many of you will no doubt have discovered for yourselves, furniture deliverers are seldom, if indeed ever on time. On this occasion, they arrived at 3:20 pm. Once they had completed the delivery, I rushed out in my car, still hoping to make my appointment. As a result, I blew straight through a speed trap and was booked. This cost me a $132 fine. Once I had dealt with the police I was still hoping to get to my interview on time, so I continued to rush, and in my haste went through a stop sign without stopping. I collided with another car and caused $4000 damage, combined, to both vehicles. I then arrived at my appointment, only to be told that they had rescheduled and interviewed the person who was to have followed me … and they had given that person the $80,000 per annum job. As a matter of logic, it would be perfectly possible to argue that the delivery drivers’ breach of the contract had led to everything that followed. Had they been there on time, I would not have needed to speed. I would have stopped at the stop sign. And I would have gotten the job. So, can I sue them for expectation damages of $84,132? Of course not. So, how do we draw a boundary around harm which must be compensated by damages, and harm which need not be so compensated? 3.1 Remoteness and causation: Hadley v Baxendale The key tests for remoteness and causation come to us from a case called Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 156 ER 145. This is another of those absolutely classic cases of English law which have been handed down over the years. In Hadley v Baxendale, the plaintiff contracted with the defendant to carry 17 a broken crankshaft to a manufacturer, who was to use the broken shaft as a model for the manufacture of a new one. The crankshaft was a key component of a flour mill operated by Hadley. Baxendale did not know that the crankshaft was the only one which Hadley had, and that as a result the flour mill would be sitting idle until the new one could be manufactured and installed. Delivery of the broken crankshaft to the manufacturer was delayed, with the result being an additional five days in which the mill was unable to operate. This, of course, meant five days without profit for the mill owner. The question was therefore whether Baxendale was liable for the lost profits as well as for the delay itself. 15126257 Alderson B gave the leading judgment, and set out what has become known as the two limbs of Hadley v Baxendale. These are: 18 First, the defendant should be liable for damage which occurs “naturally … according to the usual course of things.” This damage is the direct and immediate damage which is clearly and demonstrably linked to the breach. Second, the defendant should be liable for damage such as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it. This second limb requires a little unpacking. For the damage to reasonably be in the contemplation of both parties, then one of two things must occur: Either the plaintiff must tell the defendant the special knowledge required to foresee the loss; or The plaintiff must know that the defendant has learned the special knowledge from some other source. The result is that any damage which is not “in the natural course of things” and which cannot reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, will not be compensable. An example may help to bring this issue out more. Let’s look at Victoria Laundry v Newman Industries [1949] 2 KB 528. In this case, Victoria Laundry operated a laundry (obviously!) and also a dyeing business. Apparently the dyeing side of the business was more lucrative, and they had just obtained contracts with the Ministry of Supply which would allow the business to expand in both capacity and profitability. In order to meet this contract, they needed an additional boiler. They contracted to purchase one from Newman Industries, who knew nothing about boilers but had two available for sale, second hand. The boiler was inspected, and everyone was 19 happy, but then after it had been dismantled for transport, the boiler was damaged. This resulted in a delay, which in turn led to a delay in the expansion of the business and its ability to profit from the lucrative Ministry of Supply contracts. The question before the court was what losses should be compensated by Newman Industries. The court looked at the limbs in Hadley v Baxendale separately. It found that the normal profits of the laundry during the delay were “according to the usual course of things” and should be compensated by damages. However, the court found that the additional profits to flow from the more lucrative dyeing business were not “according to the usual course of things” and were not known to Newman Industries at the time of the contract. Accordingly, those additional profits fell outside the rule in Hadley v Baxendale, and could not be compensated by damages. 3.1.1 Nonfinancial loss Most of the time, nonfinancial losses or harm (for instance, stress and anxiety) are not able to be compensated for by damages. The exception to this is where the contract itself is intended to provide for pleasure, and fails to do so. The key example is a case we have already come across, Baltic Shipping Co v Dillon (1992) 176 CLR 344. In this case, Baltic Shipping contracted with Mrs Dillon to provide her with a 14 day cruise, and the ship sank on the tenth day. Mrs Dillon successfully argued that the whole purpose of the contract had been to provide her with pleasure. This was a pleasure cruise – not, for instance, a mere contract for transportation – and the company failed to provide her with the contracted pleasure, because she found herself aboard a sinking ship! On its face this seems pretty reasonable. You should be aware, however, that circumstances such as these are quite rare, 20 and unless it is fairly obvious that a contract was for pleasure, don’t be too hasty about arguing that a plaintiff should be compensated for nonfinancial loss. 3.2 Mitigating measures Let’s imagine for a moment that a contract between Party A and Party B has gone pear-shaped. Party B has failed to complete their obligations, and Party A is suffering damage as a result. Now let’s imagine that Party A can take steps to limit or prevent further damage (or they can do nothing, in which case the damage will get worse). What should Party A’s obligation be? A few rules apply here. 3.2.1 Rectification and repair First and foremost, if a breach leaves the innocent party in a situation where they must take steps to rectify or repair the breach, they will be able to obtain damages to compensate them for whatever expenditure was involved in the repair or rectification. The classic Australian case illustrating this point is called Bellgrove v Eldridge (1954) 90 CLR 613. In this case, Bellgrove was a builder, who contracted to build a house. Once building of the house was well underway it was discovered that the concrete used for both the foundations and the bricklaying was seriously deficient in cement. The result was that both the foundations and the walls themselves were unsafe. Eldridge wished to have the house demolished and reconstructed; Bellgrove argued that some form of underpinning, or replacement of the foundations would be adequate. The court found that the most appropriate solution in this situation was to have the house demolished and rebuilt. The 21 defaulting party, Bellgrove, was therefore liable to pay all of the costs associated with demolition, and with the rebuilding of the new structure. 9725576 3.2.2 Mitigation proper The innocent party in a transaction – that is, the party which has not breached the contract – may nevertheless find themselves with some responsibilities arising from the breach. In particular, a duty will lie upon the innocent party to take reasonable steps to mitigate the harm arising from the breach. If they do not do so, they may not be able to recover damages for the full extent of the harm caused. In other words, if there are reasonable steps open to the innocent party to minimize the extent of the harm, they should take those steps. Having said this, if the party takes those steps to mitigate, and those steps costs the innocent party money, the innocent party may be compensated for that expenditure. My favourite example of mitigation in action is a truly awesome case. One of the best we look at in contract law, and I can’t believe nobody has turned this into a movie yet. With the right scriptwriter, it would be a killer. The case is called Banco de 22 Portugal v Waterlow & Sons [1932] AC 452. Listen to this for a set of facts. The Banco de Portugal was the central bank of Portugal, responsible for the issue of banknotes. They decided to release a new banknote worth 500 escudo featuring explorer Vasco da Gama, so they made a contract with Waterlow & Sons, printers, to print 600,000 of the banknotes. Naturally, as you might imagine, there is usually a great deal of security attached to the issue of banknotes. This time, however, something went dreadfully wrong. A syndicate of criminals sent a representative to Waterlow & Sons. The criminal representative convinced Waterlow he was also a credentialed representative of the Banco de Portugal, and he placed an order for a further 580,000 of the notes. Waterlow duly printed the 580,000 notes – using the authentic dyes, authentic printing plates and authentic paper they had used for the actual notes! It gets better. Having obtained these millions of escudo, the criminals opened a bank – a genuine, government-registered bank! They used the counterfeit money to capitalize the bank, and put the rest in circulation. Soon enough, authorities became aware that there was a problem. The Banco de Portugal had few options. The only real way to control the problem was to recall all of the da Gama banknotes, replacing them with other notes of equivalent value. This meant they were stuck in the position of paying for known counterfeit notes, but at least it removed them from circulation and prevented any further counterfeit notes from being circulated. Of course, all this came at a massive cost – however the alternative was potentially the collapse of the entire Portuguese economy. 23 Naturally, Banco de Portugal sued. And naturally, Waterlow admitted liability – however they said that the only liability was for the paper and ink. They argued that the expenditure made by the bank in honouring the counterfeit notes was the bank’s own decision. The court disagreed. The bank’s decision to honour all of the notes was a reasonable mitigating measure. If the bank had attempted to honour none of the notes, this would have utterly undermined confidence in the economy, with disastrous results. As a result, the measures taken by the bank were reasonable mitigating measures, and Waterlow & Sons had to foot the entire bill – over £600,000. Adjusted for inflation and converted to Australian dollars, this judgment was for just under $65.7 Million Australian. Yes, you read that right. 65 MILLION. What a fantastic heist. 3.3 Contributory Negligence Contributory negligence is a concept which will likely be more familiar to you from your study of torts, rather than your study of contracts. However negligence on the part of the plaintiff will now be relevant to the calculation of damages. This is a relatively recent development in law, but a welcome one. In short, if a plaintiff is negligent in relation to a breach and their negligence contributes to the harm, they will be unable to recover damages for that part of the harm which was due to their own negligence. The best contract case to understand this is Lexmead v Lewis [1982] AC 225. In this case, a farmer purchased a towbar which would allow him to tow a trailer behind his farm vehicle. The hitch as delivered and installed was defective, and the farmer knew it. So, at this point, we quite clearly have a breach on the part of the supplier. What the farmer should have done at this point is return the car to the supplier and demand that the 24 defect be repaired or replaced. However he did not do so. In fact, he continued to use the towbar for months. Eventually, the worst happened. The towbar failed dramatically and the trailer tumbled free. The trailer crashed into a moving car and killed two people in the car. A third person in the car sued the trailer in tort. The farmer, in turn, took action against the supplier of the towbar, claiming damages for the defective towbar. There is a very difficult question to be answered here, isn’t there? Were these deaths caused by the defective towbar? Or were they in fact caused by the farmer’s negligence in continuing to use the towbar, even though he knew it was defective? In the end, the court found that the farmer’s negligence had broken the chain of causation in this case. If the accident had happened soon after the installation of the towbar, or if the farmer had not known of the defect, things might have been different. However, the fact that the farmer knew he was towing the trailer with a defective towbar meant that his decision-making was the key cause of the harm in question, not the defective towbar. No doubt the supplier would have remained liable for the breach (and therefore liable to replace or repair the towbar) but the supplier was not responsible for the fatal accident. 25 5461266 3.4 Review questions Question 4 What is the first limb of the rule in Hadley v Baxendale? a) Damages represent the usual remedy in common law; b) Damages compensate the harm which arises naturally from the breach; c) Common law damages are given in preference to liquidated damages; d) Causation must be demonstrated to the satisfaction of a reasonable person. Answer: (b) 26 Question 5 What rule was upheld in the case Bellgrove v Eldridge? a) Damages cannot be given for non-economic loss; b) Damages can be given for harm which was reasonably contemplated by both parties at the time of contract formation; c) Parties must be ad idem in relation to liquidated damages; d) The innocent party can obtain damages to cover the reasonable cost of rectification or repair. Answer: (d) Question 6 When can damages be awarded for non-economic loss? a) When the non-economic loss can be properly quantified b) When the non-economic loss was reasonably within the contemplation of the parties at the time of contract formation; c) When the explicit purpose of the contract was to provide a non-economic benefit; d) When the parties have failed to provide liquidated damages in relation to non-economic loss Answer: (c) 4.0 Anticipatory breach Last week we looked at the topic of anticipatory breach. This occurs when a party has, either explicitly or by implication, repudiated the contract, but has done so before the time their obligation falls due. We learned last week that when this occurs, the innocent party has two options. First, they can 27 terminate the contract. Alternatively, they can allow the contract to continue, and wait for the actual non-performance of contractual obligations, at which time they can take action for damages in the normal way. Now, we are considering the damages arising from anticipatory breach where the contract has been repudiated. It makes sense, as a result, that we can only be talking about situations where the innocent party has terminated the contract. After all, if they have chosen not to terminate the contract, the breach hasn’t happened yet – so we can’t be calculating damages! Even though a party may choose to terminate a contract early due to anticipatory breach, the date at which damages are calculated remains the date at which the obligation was due. This makes sense. If we are talking about a situation of anticipatory breach, then the breach itself hasn’t occurred yet, so it would make no sense to assess damages on the date the contract was terminated. However, as soon as the innocent party has chosen to terminate the contract, they become subject to the usual duties to mitigate their losses. So, in a case of anticipatory breach, the duty to take reasonable steps to mitigate losses arises at the time of termination, not at the time the obligation fell due. Make sense? Perhaps a case example will help. Let’s look at Shindler v Northern Raincoat [1960] 2 All ER 239. In this case Shindler was appointed as the Managing Director of the Northern Raincoat Company on a ten year contract. Sometime later, a company named Mandleberg took a controlling interest in Northern Raincoat. They indicated that they did not wish Shindler to continue in his position as Managing Director, but they were prepared to employ him in some other (initially 28 unspecified) capacity, at the same salary he had earned as Managing Director. Shindler was informed of the intention to dismiss him. This, as we know, was a repudiation of the contract, because it indicated that the company was now unwilling to complete the contract. Shindler was therefore in a position to terminate the contract if he wished, at this point, on the basis of anticipatory breach. Shindler played it more carefully than that. He indicated that he was likely to sue for breach of contract if he was dismissed, and he started to negotiate in relation to other potential opportunities within the company. However he continued to fulfil the duties of Managing Director, and did not terminate his contract. In the end, he was unable to come to terms with the company and sued, at that time, for anticipatory breach. Now we come to the interesting question. Should Shindler be able to recover for all of the wages he would have been paid had he completed his term as Managing Director? Or, alternatively, should he have mitigated his losses by accepting one of the other job offers made by the company? The court found that even though the company had repudiated the contract by indicating its intent to dismiss Shindler, Shindler had not initially accepted the repudiation, so the contract had not initially been terminated. As a result, when the subsequent job offers were made, the initial contract still existed. Since the initial contract still existed, Shindler was not under any obligation to mitigate his damages. By the time he did terminate the contract, negotiations had broken down. As a result, Shindler had never been under any obligation to mitigate his damages. 29 On the other hand, if Shindler had terminated the contract as soon as he had been told he was to be sacked, then he would have been obliged to take reasonable steps to mitigate his loss – including accepting the offered substitute positions. 5.0 Equitable remedies In this final section (of what has become a rather long topic – but this could not be helped), we discuss equitable remedies. The doctrines of equity were called into operation by some plaintiffs who found that damages were not always a good remedy for the breaches they had encountered. Equity, on the other hand, offers a range of potential remedies which can enable the court to fashion a more effective remedy. However, before we get stuck into the remedies themselves, there are two key points you must understand (especially since none of you are likely to have studied equity as a subject just yet). First, an important equitable principle states that equity follows the law. In other words, equitable remedies will only be available if the court is satisfied that the common law remedy (damages) is inadequate, and if there is no satisfactory remedy in statute law (such as the Australian Consumer Law). If either of those will work, equitable remedies will not be used. Second, equitable remedies are discretionary. Damages are available as a right: if a plaintiff can demonstrate the cause of action, then they will have their damages. Equity doesn’t work like that. A party can establish the cause of action, and yet a court of equity may still decide that their desired remedy is not available to them. So, while this section looks at some of the equitable remedies, it is not possible to set out legal tests for 30 when each remedy will be available. Simply enough, they will be available when the court decides they are available. So, with that understood, let’s look at the remedies. 5.1 Specific performance Specific performance is exactly what it sounds like: in this situation, the contract has not been fully executed as yet. The breach most likely consists of that part of the contract which has not been completed. The court, in this situation, can direct the defaulting party to perform their obligation. The classic situation for specific performance is a contract for the sale of an interest in land. In this situation, the defaulting party has often failed to convey the title to the purchaser; or else they have failed to convey the title in the form required under the contract. An order for specific performance would require them to proceed to complete their obligation. In Turner v Bladin (1951) 82 CLR 463, the opposite was the case. Bladin were selling a quarry to Turner, who was to pay in a series of instalments. The quarry had been conveyed to Turner, who had then failed to pay all of the instalments. An order for specific performance was given, to force payment of the rest of the money. However, there are a range of circumstances in which specific performance is very unlikely to be granted. First, specific performance is unlikely to be granted if the obligation is not sufficiently clearly spelt out in the contract. That makes sense: the court must be certain about what it is requiring the party to specifically perform! Second, the court will not require specific performance if this in turn would require the ongoing supervision of the court. This is 31 held to especially apply to contracts for “personal services” where performance would be ongoing for some period of time. It would not be as though the court could oversee ongoing performance in the same way that it can enforce a single (or limited number of) discrete and identifiable acts. 5.2 Injunction By now most of you will be familiar with at least the concept of injunctions. An injunction is an order to undertake, or refrain from, some specific act. Injunctions come in two types: an interlocutory injunction, which is almost like an emergency measure to freeze the parties in their current positions and prevent further harm while the whole legal mess is sorted out; and final injunctions. We will concentrate for the moment on interlocutory injunctions, as these are the most common. Interlocutory injunctions are a very useful tool for the court to have, as they do preserve the status quo and prevent further harm, especially where legal proceedings are likely to be protracted or where the harm is likely to accumulate. Having said this, interlocutory injunctions have the potential to work injustice. The party subject to the injunction has its freedom curtailed, and this should only occur on good grounds. Consequently the court has developed a test for the application of interlocutory injunctions: First, the application of equity must be appropriate. So, the plaintiff must show that damages would not be an appropriate remedy in the ultimate case. Second, the court must be satisfied that there is a serious question to be tried. This does not mean the court must be satisfied that the plaintiff will win; rather, the court must be satisfied that the plaintiff has at least a prima facie case. 32 Third, the interim relief must be justified, taking into account the potential future harm, and the limits upon the defendant if the injunction is granted (this is called the balance of convenience). A good example of the High Court implementing this test can be found in Castlemaine Tooheys v South Australia (1986) 161 CLR 148, although this is a constitutional case and not a contract case. In this case, South Australia had amended its legislative scheme for the recycling of bottles, to impose much higher penalties. Castlemaine Tooheys sought an injunction to prevent South Australia from prosecuting under the new provisions, while a constitutional question (relating to tariffs on interstate trade) was tried. www.virtualtourist.com Did somebody mention beer? In this case damages were not available, so the first question was disposed of. The court was satisfied that there was a serious question to be tried. However, balancing the danger to the environment of littered bottles against the plaintiff’s interests in avoiding prosecution, the court found that the 33 balance of convenience did not favour the plaintiff. The injunction was not granted. 5.3 Rescission Rescission is a concept we have already come across several times, and it requires little explanation. The best case is an old friend: Luna Park v Tramways. Remember how in that case, once a condition of the contract was breached, Luna Park terminated the contract and stopped paying? That was rescission in action. Rescission does not require the intervention of the courts. Simply put, once a condition is breached or a contract repudiated, the innocent party has the right of rescission: the right to terminate the contract. The other party can, of course, sue on the basis that the contract was wrongfully terminated. If they win, then the court will hold that the party which has wrongfully terminated the contract has in fact repudiated the contract themselves – and they will be liable for damages! Consequently, repudiation is only a good idea if one is absolutely sure that it is justified. 5.4 Restitution Finally, we come to restitution. Restitution arises from the equitable concept of unjust enrichment. In essence, the concept of restitution is that if one party is unjustly enriched at the expense of the other party, then the court may make an order in restitution to correct the injustice. The doctrine was first noted in a rather aged and complicated case called Moses v MacFerlan (1760) 97 ER 676. Much of the case is almost incomprehensible by now, except perhaps to legal historians. However what happened in the case was that Moses held some promissory notes (formal IOUs) from a third 34 party. He endorsed them in favour of MacFerlan: that is, he signed the debts over to MacFerlan, so that MacFerlan was now the owner of the debts. Technically, MacFerlan could potentially recover the money from either the third party or from Moses. However MacFerlan stated that he would not trouble Moses further in relation to the debts. Sometime later, he apparently changed his mind, sued, and won. The judgment cited here considered whether it would be conscionable for MacFerlan to retain the money, even though he had been awarded it by a court. Lord Mansfield indicates, in his judgment, that it would be inequitable for MacFerlan to do so because even though MacFerlan was right at law, natural justice demanded otherwise. This is the foundation of restitution. In its modern sense, restitution is really only applied in a few limited situations: To recover money paid by mistake (for instance, under the mistaken impression that a debt was due); To recover money paid when there has been a total failure of consideration; To recover money which was to have been paid for work preceding a contract (so, for instance, someone has commenced work in anticipation of a contract being formed, but the contract then fails to be formed); and To recover money for work done under a contract which cannot, for some reason, be enforced (for instance, because the contract is or becomes void). You can see that each of these represent situations in which it would be contrary to equity for the recipient of the money to 35 retain it. If necessary, the courts can exercise the doctrine of restitution to force this money to be repaid. 5.5 Review questions Question 7 Under what circumstances is specific performance unlikely to be granted? a) If performance would require the ongoing supervision of the court; b) If performance is rendered impossible because the contract has been repudiated; c) If performance has been rendered impossible by a selfinduced frustrating event; d) If performance would require expenditure not reasonably within the contemplation of the parties at the time of contract formation. Answer: (a) Question 8 If damages would be an adequate remedy for a breach, but equitable remedies would provide a more convenient manner of addressing the breach, which remedy will be applied? a) The common law remedy (damages); b) The equitable remedy; c) Whichever remedy is claimed by the plaintiff; d) Whichever remedy the court considers most appropriate. 36 Answer: (a) 6.0 Review Last week we examined the circumstances in which a contract may be breached. This week we’ve taken the final step in our logical process, by examining the circumstances which follow such a breach. If you think about it, this week’s material is perhaps the most important material of all. This material tells us what the court can do to bring justice to a party which has been innocent in its conduct; which is anticipated in a contract and accepted obligations from another party, but then found that those obligations were not delivered upon. In some cases, perhaps the easiest cases to understand, the parties have agreed in the contract itself what the consequences should be if either party were to default. In this situation, if they had specified damages to be paid in, those damages will be called liquidated damages and payment of such damages will settle the dispute. Liquidated damages will not, however, be enforced when they amount to a penalty. So, if they look less like compensation and more like punishment, liquidated damages will not be enforceable. If the contract does not contain a liquidated damages clause, the court’s first preference will be to award damages to the innocent party; that is, an amount of money intended to restore the innocent party to the circumstances they would have encountered but for the breach. This may include expectation damages, to compensate the innocent party for the gain which they might reasonably expect to have obtained if the contract was properly completed. The test for the assessment of common-law damages is found in the case Hadley v Baxendale. The defaulting party will be 37 liable for damages to compensate for any harm flowing naturally from the breach, and also for any harm which was reasonably within the contemplation of the parties at the time the contract was made. In some cases, of course, no amount of money can properly compensate the innocent party. If, for one reason or another, damages will not be an appropriate remedy, the court may look to the remedies available in equity. This week we have discussed rescission, restitution, specific performance, and injunction. The latter two, in particular, provide the court with great flexibility to force the defaulting party to undertake acts which will make good the harm caused by that party’s breach. It is important to understand that these remedies are the primary form of legal redress for most contracts other than those to which the Australian Consumer Law applies. Next week we go on to examine the remedies which are available under the Australian Consumer Law. 7.0 Tutorial Problems Problem 10 This is why Crossfit and Paleo are bad for you … Please watch the short animated video at the following link, and then consider the questions below. Assume that Queensland contract law applies throughout. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mpjjEp-bVKM 38 Has the contract been breached? Assume that the Yoga Resort’s manager was secretly in league with the terrorists, and assisted them by turning off the resort’s security systems. Is there a breach now? If there is a breach, what will be subject to compensation under the first limb of Hadley v Baxendale? Would Shanna be entitled to any compensation for noneconomic loss? How would such a loss be justified under Hadley v Baxendale? [30 Minutes] 8.0 Debrief After completing this topic you should recognize: That the key remedy available in the common law is damages; That the purpose of damages is to compensate the plaintiff for the harm suffered as a result of the breach; That damages are usually assessed at the day of the breach; That damages are awarded once and for all, except in the case of a continuing breach; That damages may be awarded for the loss of expectation if a reasonable person in the position of the defendant would have realized that such losses were sufficiently likely to result from the breach; 39 That damages may only be awarded for harm which is caused by, and not too remote from, the breach. The tests for this are set out in Hadley v Baxendale: o The defendant is liable for harm which occurs naturally, according to the usual course of things; o The defendant is liable for harm which may reasonably be supposed to have been within the contemplation of both parties at the time they made their contract; That the court will also enforce liquidated damages, provided those damages do not amount to a penalty; That a plaintiff may receive damages to compensate for expenditure undertaken in reasonable mitigation of the harm; That the damages received by a plaintiff will be reduced if the plaintiff has contributed to the harm by their own negligence; and That in the event that common-law damages are insufficient or inappropriate, equitable remedies including specific performance, injunction, rescission and restitution are available to the courts. 40