Countering Eco-Terrorism in the United States: The Case of

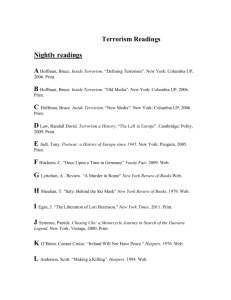

advertisement