diplomarbeit - E-Theses

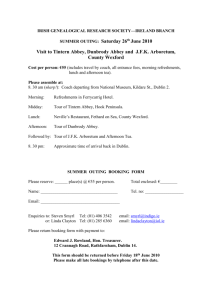

advertisement