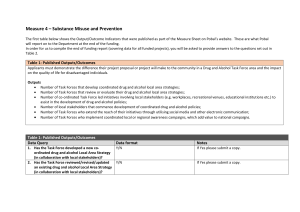

a review of mass media campaigns in road safety

advertisement