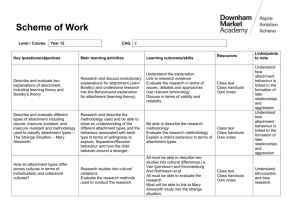

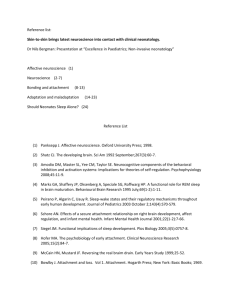

Attachment Theory & Maternal Deprivation: Thesis Introduction

advertisement