Seeing Anthropology

advertisement

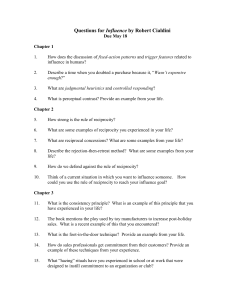

Seeing Anthropology Cultural Anthropology through Film 4th edition (abridged) by Karl G. Heider Chapter 7 Distribution and Consumption If individuals were truly self-sufficient, if everyone produced everything he or she needed, there would be no distribution, no economics, and also no societies. Exchange, the distribution of goods and services, forms the strands of social networks that bind the members of a group to each other and, reaching beyond, ally one group with another. Mutual interest may be the motivation for these associations within and between groups, but it is exchanges, both substantial and symbolic, that forge the real ties. DISTRIBUTION: MECHANISMS OF EXCHANGE In Chapter 6, we looked at production. Here, as we turn to other main interests of economics, distribution and consumption, we face a different sort of problem. As anthropologists first encountered other cultures, they found different manners of producing food, tools, or other goods, but these techniques were easily understood. They differed in details only, not in principle, from what the anthropologists had encountered at home. In contrast, distribution, or exchange, in small-scale tribal societies dealt with a whole new set of principles and posed different problems. Most importantly, there were rarely stores or markets selling products for money on an impersonal basis. Instead, many of the transactions took place as deeply embedded components of social relationships. Anthropologists generally follow three major patterns, or forms of integration, by which societies manage distribution: reciprocity, redistribution, and market exchange. These patterns blur into each other and so are not absolutely clear-cut. Also, in many societies, more than one pattern may coexist at different levels. Table 7.1 gives a general idea of what distinguishes each pattern and where each occurs. TABLE 7.1 Exchange and Society Size Reciprocity Redistribution Markets Small-scale societies (bands, tribes) Yes No No Midsized societies with some central power Yes Yes No Large-scale societies with strong centralized power Yes Yes Yes Generalized Reciprocity Reciprocity refers to a wide range of exchanges involving goods and services between relatively equal individuals or groups. We recognize three major forms of reciprocity: generalized reciprocity, balanced reciprocity, and the special case of negative reciprocity. We are really talking about a continuum along an axis of social distance, with generalized reciprocity appearing at one end and negative reciprocity found at the other end. TABLE 7.2 Three Types of Reciprocity: the Reciprocity Continuum Most anthropological attention is paid to generalized reciprocity, "gift giving," in tribal cultures, but the entire spectrum can be identified in most cultures. The extreme cases are not, strictly speaking, "reciprocity," for in neither "true gifts" nor in plunder do we see any expectation of return; rather, they are the logical extension of these principles. The visiting trade institution reproduces generalized reciprocity at the far right. Generalized Reciprocity Balanced Reciprocity Negative Reciprocity "Pure" Gift ———— Gift ———— Barter ———— Bargaining ———— Theft, Plunder Time lag of reciprocity Never Delayed Short term Immediate Never Social distance Intimate (kin) Close (kin, neighbor) Medium (friend) Medium (friend) Extreme (enemy, Other) Generalized reciprocity is the form most extensively studied by anthropologists, because it is the key to mechanisms of exchange in nonmarket economies. Also known as delayed reciprocity, it occurs between closely related or allied people or groups and involves an indirect exchange that takes time to complete: A gives to B, but B does not immediately reciprocate. This delayed exchange is made possible by close social ties (preexisting or newly created) and often creates or maintains complex relations between people. ("If friends make gifts, gifts make friends" [Sahlins, 1965:139].) Another way of formulating generalized reciprocity as a form of integration is through the concept of gift. Marcel Mauss, analyzed this sort of exchange in his important book The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (1925/1954). Mauss saw exchange, which was largely gift exchange in these "archaic societies," as deeply embedded, what he termed a "total social phenomenon." Taking a holistic perspective, he recognized that gift giving Seeing Anthropology – chapter 7 Page 1 served many different functions: legal, political, domestic, religious, economic, aesthetic, and structural. Of course, gift giving is important in more than tribal societies. As an example, let's take an American middle-class tenyear-old's birthday party. The birthday child invites a dozen friends, each of whom brings a gift having a value of a few dollars. The children get food (ice cream, cake, soft drinks), perhaps a minor present to take home, and entertainment (home games, an expedition to a skating rink, or the like). During the next year, the birthday child can be expected to be invited to twelve birthday parties, and should bring an exactly comparable present (sometimes, depending on the current fads, it is the same thing—a Barbie doll or Pokemon trading cards, for example). At the end of the annual cycle, everyone should be about equal. There should not be any great variations in cost of the present, impressiveness of the entertainment, or the like. So what is the point? Obviously, one function of this shuffling about of interchangeable goods and services is to strengthen ties by keeping everyone constantly in someone's debt. There is no specialization; each child buys presents at one of the same few toy stores. But the social network is being constantly strengthened. A birthday party, in Mauss's words, allows us to "catch the fleeting moment when the society and its members take emotional stock of themselves and their situation as regards others" (Mauss, 1925/1954:77, 78). What is interesting here is that the cultural idea of gift in English is something given freely, without thought of return. From an anthropological viewpoint, we could hypothesize that there is almost never such a thing as a gift in that sense. There is virtually always the expectation of return. But that very cultural ideology of the "free" gift, while technically incorrect, is part of what binds the social network. An American birthday party with presents. Mauss's formulation includes three obligations: to give gifts; to repay those gifts; and, most interestingly, to accept gifts. In these sorts of interactions, it is not acceptable to reject the social ties that a gift brings with it. There is the implication that all gifts are of this sort, implying social obligations with the expectation of return. Kula Exchange among the Trobrianders. The most famous gifts in all ethnographic literature are the simple shell bracelets and coral necklaces of the Kula Ring of the Massim District, off the eastern tip of New Guinea, which were memorably described by Bronislaw Malinowski in 1922. The Massim area includes several island and atoll groups that lie in an approximate circle (see Figure 7.1). Malinowski, doing fieldwork on the Trobriand Islands, saw how his chiefly friends had ritual counterparts located in neighboring villages both to the east and to the west. At regular intervals and with great ceremony, a chief would sail with his entourage to the east or west to pick up a gift from his kula partner. If he went to the west from the Trobriands, the gift would be a shell bracelet; if he went to the east, the gift would be a red coral necklace. Later, there would be return visits with more gifts. As Malinowski worked out the regional implications of the kula exchange system, he found that the bracelets circulated all around the circle in a clockwise fashion, while the necklaces went in a counterclockwise fashion. Malinowski described in detail how these gifts were embedded in regional social and religious systems. Mauss (in The Gift) used Malinowski's account of the Kula Ring as his prime example of a total social phenomenon. He emphasized how much other ordinary trade was carried out under the protection of the chiefly gift giving. While the leaders were engaged in the kula ritual in the village, their followers were conducting lively barter on the beach. Different islands produced different things— fine pottery, canoe wood, great yams, greenstone, or whatever—and thus the ceremonial kula exchange allowed the exchange of these other, more usable goods. Why the Kula Ring? What does it mean? What are its functions? It is certainly one of Mauss's total social phenomena, for the kula involved much of Trobriand culture: ritual (in the gift-exchange ceremonies), technology (in crafting and sailing the great seagoing canoes), politics (in the jockeying for influence), and economics (in the trading for ordinary crafts and produce that accompany the kula voyaging). Annette Weiner, who studied the Trobriands half a century after Malinowski, emphasized (1988) how men (and a few women) are motivated to participate in the extraordinary complex manipulations to establish, maintain, and profit from their kula paths (the ties they have with their various kula partners on other islands). At one level, the kula exchange represents a great context for status, with winners and losers. Weiner emphasized how the kula event is a chance for the principals to gain some international renown, a fame that they could never achieve as players at the local village or island level: Seeing Anthropology – chapter 7 Page 2 Food Sharing as Insurance. One function of gifts for Trobrianders, then, is to forge ties between potentially hostile villages or islands. But similar practices have other functions. For many of these cultures, enough environmental variability and uncertainty occur—the rain doesn't fall, the game is scarce—that no person or household unit can be assured of having enough food all the time. Sharing one's surpluses with others, in the expectation that food given out will eventually be returned, is a way of safeguarding against the inevitable bad times. This has been called a social refrigerator. We can see a double outcome of sharing. Food is distributed, and the social network is strengthened. There are many ways to institutionalize sharing. Marriage as Exchange. The most common institutionalized sorts of generalized reciprocity are the exchanges that are triggered by marriage. Although we now tend to think of marriage as the union of two individuals, in most societies marriages are more nearly unions of two groups that the fact of the marriage obligates to exchange goods and services of spouses over time. In Chapter 8 we shall explore how the extensive exchanges that take place serve to integrate, or bind together, the two groups. Balanced and Negative Reciprocity Balanced reciprocity is found further along our gift-giving spectrum (see Table 7.2). This type of exchange takes place between more distant people (distant in geographical or social terms), the reciprocity is more immediate (without a long delay), the goods involved are of relatively balanced or equal value, and the long-term social consequences are less important. Barter, the overt negotiation of exchange, is more likely to occur. The Kula Ring of the Trobriand Islands, for example, was a two-tiered economic institution In village ceremonies the high-status men presented gifts that would eventually be reciprocated (generalized reciprocity), while their followers brought goods to be unceremoniously bartered on the beach (balanced reciprocity). Another example of balanced reciprocity can be found in the barter economy that involves many people in the United States today. A dentist and an auto mechanic may exchange services, thereby avoiding cash and income tax liability. Negative Reciprocity. Continuing along our continuum, as the social distance increases, the nature of the exchange shifts from a concern for social ties toward an antagonistic stance of maximizing personal gain. Bargaining becomes sharper and eventually we wind up at the far right of the spectrum with outright trickery, theft, and plunder, which are, indeed, types of negative reciprocity. The parties are no longer kin, allies, or friends but rather enemies or the Other. it is therefore safe to consider them deserving of abuse (if one can get away with it). The Vikings practiced negative reciprocity for centuries, swooping down out of Scandinavia to plunder the English coastal settlements of goods and slaves. A Solution: Visiting Trade Institutions. If these principles were absolute laws, long-distance trade would be impossible. But trade is desirable, and one widespread solution is to create a nominal kinshiplike relationship between distant and otherwise unrelated people. These individuals are often called "trading partners." For example, the distant partners of kula exchange, which we discussed under the aegis of "generalized reciprocity," could often be part of visiting trade institutions. Redistribution Redistribution involves the distribution of some of a rich person's wealth, or the gathering together, or pooling, of resources in a common pool, followed by a reallocation of these resources. In these cases, no expectation of reciprocity exists. Individuals may relinquish some of their resources, perhaps in the expectation that they will later benefit in some way. Redistribution usually requires some centralized power to assure the incoming contributions and to determine the outgoing expenditures. Taxation is a prime example of that redistribution. When the rich contribute proportionally more than the poor, it is called progressive taxation and has some economic equalizing, or leveling effect. When the poor contribute more in proportion to their wealth, it is regressive taxation and increases the economic stratification. Market Exchange In the institution of market exchange, goods and services are exchanged for money, with the price being set by the "market forces" of supply and demand (Plattner, 1984; Narotzky, 1997). Unlike the forms of reciprocity, market exchange functions in an impersonal way, unaffected by ties of kinship or other alliances. In fact, the ideal function of supply and demand is often overridden by other forces, particularly the monopolistic powers of producers or distributors or the governmental powers of the state. These issues quickly merge into political or moral issues. "Price fixing" is a negative term for monopolistic violation of the supply and demand function, and "black market" is a negative term for the functioning of supply and demand in the face of state monopolies. Garage Sales: Blending Markets and Gifts. Even as we deal with various sorts of reciprocity, redistribution, and market exchange, it is important to remember that these categories are not absolute and exclusive. Any individual, or any culture, is likely to use more than one in its economic life. An ethnographic study of U.S. garage sales, for example, showed how the principles of markets and gifts can be blended. Gretchen M. Herrmann did her fieldwork in upstate New York, attending more than 1,000 garage sales and interviewing more than 200 participants (1997). Garage sales (and their close cousins, such as yard sales) have been commonplace in the United States since the late 1960s and are now an important means of circulating all manner of household goods, clothing, books, and other items that are still usable. Herrmann describes the cultural schema for a garage sale: Seeing Anthropology – chapter 7 Page 3 It is held in or near the residence of the seller (not on sidewalks, in empty lots, or from stalls at a swap meet). The goods are personal possessions, used by the seller. The goods are in decent condition, and the prices are well below retail prices. Buyers are expected to act almost like guests—not arriving before the stated time, and not bargaining too aggressively—and are to buy for their own personal use, rather than for resale. In short, the bundle of cultural ideas that makes up the garage sale schema melds market with gift. Of course, goods are sold for money, but the impersonal and profit-maximizing features of the market are severely mitigated by giftlike features. Buyers are not really personal guests of the sellers, but some of that relationship is suggested. The goods are not exactly given away, but the prices are unreasonably low. In fact, Herrmann describes many instances where the sellers virtually give away extra objects because they feel that the buyers will provide "a good home." DOING ANTHROPOLOGY Your Own Transactions Think of all the transactions in which you have been involved recently. You could categorize them as reciprocity, redistribution, or market exchange, but you would soon think of instances that did not fit nicely into any of these categories. Go beyond the labels, and use the following attributes to describe your transactions: 1. What was the nature of the reciprocity (immediate, delayed)? 2. What social ties were involved (nonexistent, casual, lifelong)? 3. Was the transaction voluntary or obligatory? 4. What is being exchanged (goods, services, currency)? CONSUMPTION—FOOD The third general concern of economics is consumption, or how things are used. We can look at how houses, or tools, or clothing is used. But here let us concentrate on food, for of all sorts of consumption, eating and drinking reveal the most about a culture—about its social relations and patterns of meaning. Food is newly produced, distributed, and consumed daily by virtually every human being. Its consumption is important and overt, and it is a part of daily decision making to a far greater degree than, say, housing or attire. Foods That Are Not Eaten If you make a list of all the possible foods available to Homo sapiens, it is almost endless. Each item is probably eaten somewhere by someone, but no one person would willingly eat everything. There are many reasons for this reluctance: Personal idiosyncratic preference: Even people who generally share the same culture commonly vary in what they like to eat. If you grew up in a large family or regularly eat in a school cafeteria, you are well aware of this variability. Health reasons: Following the advice of a physician or for self-imposed reasons, many people abstain from certain foods in the hope that they can improve their overall health. Moral reasons: In otherwise omnivorous societies, some people may practice some degree of vegetarianism out of a dislike of killing animals. Religious reasons: An explicit proscription on eating (or drinking) certain things may be part of formal religious doctrine. Alcohol, caffeinated drinks, beef, and pork are the best known of such prohibitions. Fasting. In addition to certain prohibitions for certain foods, many cultures ban eating (and, often, sex) at certain times. Most famous is the Muslim fasting during the ninth month, Ramadan, when eating, drinking, and sexual activity are forbidden from dawn to dusk. Christians may fast, or at least abstain from a favorite food, during Lent, the 40 days before Easter. And, until recently, Roman Catholics in the United States ate fish instead of meat on Fridays. Eating Together: Social and Ritual Commensuality, sociable eating together at ritual occasions, is one of the most widespread human practices. (Think of all the different social and religious meanings of group eating in your own experience.) In Chapter 11 we shall discuss rituals as rites of intensification, which function to create or strengthen social bonds. There seems to be no more effective way to bring together friends, relations, or strangers than to serve a communal meal. But it is not just eating itself that does the job. Often specially meaningful foods are prescribed. In the United States such special foods may symbolize the in-group members in contrast to particular others: the Thanksgiving turkey is notEnglish; the Easter ham is not Jewish. Foodways and Nutritional Anthropology The term foodways is used for studies that approach a culture with a broad perspective via the people's food. It is a food-based ethnography of a culture, starting with the food and following it in a holistic manner, tracing how the food relates to the various other realms of the culture: social ties, magic and religion, medicine, sexuality, architecture and other artifacts, identity—these are just some of the aspects of culture that are tied to food. DOING ANTHROPOLOGY Global Consumption The global economy did not begin in recent decades—the centuries-long history of tea, coffee, and chocolate sweetened by sugar is a neat example of the story of global trade. To what degree are you today consuming products from around the world? Make a list of the origins—to the extent that you know them—of your food and clothing. How many countries have contributed to your lifestyle? Seeing Anthropology – chapter 7 Page 4 SEEING ANTHROPOLOGY Appeals to Santiago Photographer and Director: Arnold Baskin Ethnographers: Duane Metzger and Written by Carter Wilson Robert Ravicz Appeals to Santiago describes the cargo system of the Mayans in Chiapas, Mexico. It was shot in Tenejapa, in the Tzeltal Maya region, some 16 miles from Zinacantan, the center of Tzotzil Maya, where Frank Cancian studied a comparable cargo system. The film uses an insider's voice, or point of view, rather than that of an analytical anthropologist. It is not didactic or etic, but emic. The opening words are "My name is Alonso Teh," and it presents the cargo system through his perspective as Alonso Teh comes into the town of Tenejapa: "I've come to work in the Fiesta of Santiago." Ostensibly, there is no analysis, just the voice of Alonso Teh presenting the Mayan understanding of these ceremonies. The short clip begins with Alonzo Teh explaining the roles and intentions of the cargo officers, comparing the captains who supervise one fiesta and the mayordomos who serve their saint for a full year. These men come to the town to live while carrying out their ritual duties. Captains gather in each captain's house to plan events, drink together, play flute music, and commit to remain pure and avoid conflict while serving their saint. The film also shows ritual ceremonies when this year's mayor-demos transfer holy bundles containing the saint's raiments to the next year's mayordomos. We see the old mayordomos dancing with their holy bundles, processing to the church with the bundles, and passing them to the new mayordomos, who take on the duties for the next year. Though this event is considered a Christian ceremony, centered in the Roman Catholic church in Tenejapa, the film's focus is on the laymen who serve as cargo bearers. There is no sign of the Catholic priest, though some of the ritual activities do take place in or near church buildings or plazas. Setup Questions 1. Look carefully at what people are wearing. The Chiapas Mayans are famous for their colorful woven cloths and ribbon-decorated hats. Each local area has its own designs. 2. According to Alonzo Teh, why do men agree to become captains? What other reasons does he consider not to be correct? 3. What evidence do you find in the film for comparing captains with mayordornos in terms of their contributions to economic redistribution? 4. As the cargo is physically passed from one year's guardians to the next, Alonzo Teh lists the year's activities that lie ahead. What are these activities? CHAPTER SUMMARY Human social groups are never completely self-sufficient, but always seem to exchange some products with other groups. The social ties resulting from these exchanges may be more significant than the value of the goods themselves. There are three forms of distribution or exchange that move goods and integrate different social groups together (however loosely): reciprocity, redistribution, and market exchange. Reciprocity is the exchange of goods between relatively equal parties. When the reciprocity is completed immediately, the exchange is called balanced reciprocity and usually involves barter; when the exchange is delayed or left incomplete, we are dealing with "gifts." The giving of gifts (and the expectation of reciprocal giving) creates special bonds, often involves rituals, and establishes kinlike ties and other cultural features composing a "total social phenomenon" in holistic terms. The special case of negative reciprocity is the attempt to get something for nothing through theft or trickery; it is really an antireciprocity. Redistribution, or pooling, occurs when goods are gathered together and then redistributed, usually for the benefit of the leaders who are powerful enough to command compliance. Taxation is a good example of redistribution, as are the potlatch competitive feasting ceremonies of the Northwest Coast and the Mayan cargo system. In market exchange, products are valued in money terms and exchanged for money. KEY TERMS balanced reciprocity barter cargo system consumption distribution exchange foodways generalized reciprocity gift leveling effect market exchange negative reciprocity reciprocity redistribution taxation total social phenomenon QUESTIONS TO THINK ABOUT 1. Can there be "pure gifts"? Can you give examples? Can you formulate principles that would govern the existence of "pure gifts"? 2. Thinking about the ambiguous nature of garage sales, can you analyze similarly ambiguous institutions in your own culture (like bake sales, for example)? Seeing Anthropology – chapter 7 Page 5