Lectures on EU Competition Law

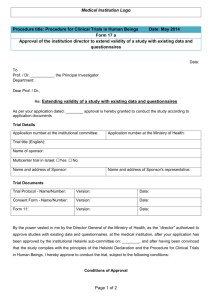

advertisement