Research Study on Internet Education Final Report

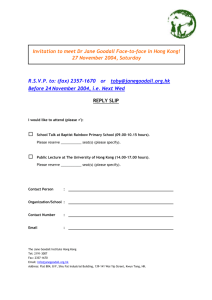

advertisement