Teaching: Accreditation of Programs for Young Children Standard 3

advertisement

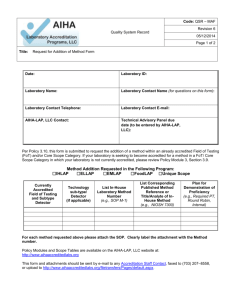

March, 2011, No. 1 Trend Briefs Trend Briefs are communications from the NAEYC Academy for Early Childhood Program Accreditation intended to share data on programs seeking accreditation and to connect the findings to early childhood research trends. Teaching Accreditation of Programs for Young Children Standard 3 T his is the first in a series of Trend Briefs to provide a snapshot of data captured by the NAEYC Reliability and Validity Study 1 (ReVal-1).1 ReVal-1 is the first in a set of studies exploring the reliability and validity of the accreditation site visit assessment tools and processes that were developed and field tested for the 2006 revision to NAEYC accreditation process for programs for young children. The analysis of this data provides insight into the performance of early childhood programs seeking accreditation. This brief provides data on specific criteria within the Teaching Standard that differentiate programs that achieve accreditation from those that do not. Beyond its technical use, the data tells the story of successful approaches used by teachers to engage children in high quality programs. We intend that this brief will inform practitioners about the data findings, deepening their knowledge. We also hope to connect the daily activities that take place in programs to the wider implications of informing best practice in early education programs. Findings Examining program performance data on Standard 3’s seven Topic Areas and 67 teaching criteria, we compared the pass rates for 114 programs accredited by NAEYC to those that were not accredited (13 Programs). For example, criterion 3.G.03 was met in 90% of the programs that became accredited, but it was met in only 31% of the programs that were deferred or denied accreditation, showing a difference in pass rate of approximately 60 percentage points (see figure 1). The average pass rate difference for the criteria within each of the 7 topic areas in Standard 3 are shown in Table 1. Note that these rates represent the average pass rate across the criteria in a given topic. Across all topics, the pass rate was higher among accredited programs than those not accredited, although the difference in pass rates (in absolute percentage points) varied across topics, from a low of 7.9 points to a high of 32.7 points. As noted in Table 1, pass rates differed between accredited and not-accredited programs in each of the 7 topic areas in Standard 3. It is also possible to examine each of the 67 specific criteria in Standard 3. From this set, 18 individual criteria showed the greatest differences in how often they were met in accredited programs when compared to not- accredited programs. Pass rate differences for these 18 criteria are shown in Table 2; they range from 30.7% to nearly 60%. The criteria that demonstrated the greatest pass rate differences (as noted above) mapped onto several key themes related to scaffolding. About the Reliability and Validity Study (ReVal–1) NAEYC Accreditation requires programs to demonstrate their ongoing capacity to meet each of the 10 NAEYC Early Childhood Program Standards. Each program standard is defined by a set of accreditation criteria which are organized into topic areas. There are 417 criteria across the 10 standards. The primary goals of ReVal-1 were to describe the standards and criteria (e.g., pass rates, means, variance) across and within the measurement tools; to replicate the initial field study findings of internal consistency within the 10 program standards; and to relate standards and criteria to accreditation outcomes (i.e., whether the programs became accredited or not). The ReVal-1 sample included approximately 130 programs receiving accreditation site visits between September 2009 and July 2010. During these visits, experienced assessors captured data on all 417 of NAEYC’s criteria. Programs in the ReVal-1 study were scored, like other programs, on only a subset of the criteria for purposes of their accreditation decision. In this sample, 114 programs were ultimately accredited and 13 were not accredited (8 were deferred, 5 were denied). 1 March 2011, No. 1 Scaffolding as Developmentally Appropriate Practice Five criteria (3.E.01, 3.E.02, 3.E.04, 3.G.03, 3.G.08) include content that speak specifically about scaffolding, reflecting its importance as a teaching strategy for enhancing program quality. Scaffolding has emerged as a critical teaching strategy for enhancing children’s learning. Strongly supported by research, scaffolding is a teaching strategy that strives to help children reach beyond their current competence in any area.2 It has been found to increase children’s executive functioning, vocabulary growth, reading comprehension, and literacy skills.3 The importance of scaffolding children’s learning is reflected in the literature that stresses the importance of teachers implementing learning activities that draw on children’s experiences, backgrounds, and interests.4 Teachers identify the child’s current understanding of a concept and seek to raise that level of understanding by adapting their instruction in ways that best fit the child. To effectively scaffold young children’s development, teachers need to couple their knowledge of practice with their understanding of the children being served and the intended outcomes of instruction. They intentionally choose from among a number of teaching strategies or adapt these teaching strategies depending on the needs of the child and the targeted learning goal. Likewise, they accept a dynamic role in the learning process, at times leading the child, at other times responding to the child’s lead, and at times engaging in reciprocal interaction. Use of multiple teaching strategies Two criteria (3.G.01, 3.G.02) address the availability and use of several strategies as a highly effective practice in early childhood education. Teaching strategies, as used here, refers to the broad context of instruction—the ways in which teachers structure the environment for children’s learning.5 Teachers may provide activities that are largely controlled, structured experiences for young children but may also allow children to engage in relatively unstructured activity. Both approaches have been shown to be advantageous for aspects of children’s learning.6 Some research strongly supports the idea that all activities, including play, should be guided or scaffolded at some level in order to maximize the children’s learning experience.7 Other research has linked the benefits of unstructured activities such as dramatic play to language and cognitive development.8 In determining the level of structure for the activity, teachers should reflect on the needs of the child and align the activity accordingly. Teachers may also interact with children in groups of varying sizes (typically small or large group) or individually. Research on group size tends to show more favorable learning out- comes for children working in small groups.9 2 3.G.03: As children learn and acquire new skills, teachers use their knowledge of children’s abilities to finetune their teaching support. Teachers adjust challenges as children gain competence and understanding. Reciprocal and guided interactions Eight criteria speak to the nature of the interactions between teacher and child. Four criteria (3.B.09, 3.E.02, 3.E.07, 3.F.07) highlight reciprocal interaction; 4 criteria (3.B.09, 3.E.03, 3.G.02, 3.G.07) address aspects of specifically child-initiated and/or adult-initiated teaching strategies to promote learning. Just as scaffolding assumes some flexibility in the use of general teaching strategies, it also provides for different styles of interaction. At its broadest level, scaffolding requires some reciprocal interaction between the teacher and child; this fosters a sense of shared experience, and also has been shown to increase child learning and engagement. At the same time, there is room for each participant in the interaction, the teacher and child, to lead. Child- initiated instruction is effective in that children are allowed to choose activities that build on areas that have already captured their interests and are at a level close to their current abilities.10 On the other hand, adult-guided strategies (direct instruction, modeling, guidance, etc.) have also been found to be effective in engaging children and in supporting a child’s growth in skills.11 When teachers are effectively scaffolding children’s development, the style of interaction would be expected to be fluid, blending opportunities for the child to lead the activity with moments of teacher-led focus and shared or reciprocal interaction. Figure 1: Scaffolding, Criterion 3.G.03 Met/Not Met Rates for Accredited vs. Not-Accredited Programs 100% 10% 80% 69% 60% 40% 90% 20% 31% 0% Accredited Programs Not Met Deferred or Denied Programs Met Note: Data based upon observations at 127 programs; 114 of these were accredited and 13 were not accredited (8 deferred and 5 denied). March 2011, No. 1 Table 1. Standard 3. Teaching: Topics, Number of Criteria in Each Topic, Topic Area, and Average Difference in Pass Rate between Accredited and Not-Accredited Programs Topic Area Number of Criteria Average Pass Rate Difference A. Designing Enriched Learning Environments 7 criteria 16.8 B. Creating Caring Communities for Learning 13 criteria 20.6 5 criteria 7.9 12 criteria 9.1 E. Responding to Children’s Interests and Needs 9 criteria 32.7 F. Making Learning Meaningful for All Children 7 criteria 14.6 14 criteria 31.2 C. Supervising Children D. Using Time, Grouping, and Routines to Achieve Learning Goals G. Using Instruction to Deepen Children’s Understanding and Build Their Skills and Knowledge Note: Data based upon observations at 127 programs; 114 of these were accredited and 13 were not accredited (8 deferred and 5 denied). The Average Pass Rate difference was calculated considering the difference in pass rates for each of the criteria within the topic area. Table 2. Standard 3. Teaching: Criteria with the Greatest Difference in Pass Rate between Accredited Programs and Programs Not-Accredited Criterion Difference Dif.Rank Criterion Language 3.G.03 59.6% 1 As children learn and acquire new skills, teachers use their knowledge of children's abilities to fine-tune their teaching support. Teachers adjust challenges as children gain competence and understanding. 3.B.08 56.4% 2 Teachers notice patterns in children's challenging behaviors to provide thoughtful, consistent, and individualized responses. 3.E.04 55.4% 3 Teachers use their knowledge of individual children to modify strategies and materials to enhance children's learning. 3.B.09 50.0% 4 Teaching staff create a climate of respect for infants by looking for as well as listening and responding to verbal and nonverbal cues. 3.G.07 47.7% 5 Teachers use their knowledge of content to pose problems and ask questions that stimulate children's thinking. Teachers help children express their ideas and build on the meaning of their experiences. 3.E.01 43.3% 6 Teaching staff reorganize the environment when necessary to help children explore new concepts and topics, sustain their activities, and extend their learning. 3.A.02 40.7% 7 Teachers design an environment that protects children's health and safety at all times. 3.G.08 40.7% 8 Teachers help children identify and use prior knowledge. They provide experiences that extend and challenge children's current understandings. 3.F.07 40.0% 9 Teaching staff use varied vocabulary and engage in sustained conversations with children about their experiences. 3.G.02 40.0% 10[Abridged] Teachers use multiple sources to identify what children have learned; adapt curriculum to meet children's needs and interests; foster curiosity; extend engagement; and support self-initiated learning. 3.A.07 38.3% 11 Teaching staff and children work together to arrange classroom materials in predictable ways so children know where to find things and where to put them away. 3.E.02 37.2% 12 Teachers scaffold children's learning by modifying the schedule, intentionally arranging the equipment, and making themselves available to children. 3.E.08 36.5% 13 Teachers use their knowledge of children's social relationships, interests, ideas, and skills to tailor learning opportunities for groups and individuals. 3.E.03 35.4% 14 Teachers use children's interest in and curiosity about the world to engage them with new content and developmental skills. 3.B.06 35.0% 15 Teachers manage behavior and implement classroom rules and expectations in a manner that is consistent and predictable. 3.D.09 32.3% 16 Teaching staff help children follow a predictable but flexible daily routine by providing time and support for transitions. 3.G.01 32.1% 17 Teachers have and use a variety of teaching strategies that include a broad range of approaches and responses. 3.E.07 30.7% 18 Teaching staff actively seek to understand infants' needs and desires by recognizing and responding to their nonverbal cues and by using simple language. Note: Data based upon observations at 127 programs; 114 of these were accredited and 13 were not accredited (8 deferred and 5 denied). 3 March 2011, No. 1 Establishing rules and routines Four criteria (3.A.02, 3.A.07, 3.B.06, 3.D.09) relate to the importance of structure through the establishment and maintenance of rules and routines within the early childhood classroom. While flexibility of instruction, use of multiple strategies, and combining reciprocal with adultdirected and child-directed activities are important components of scaffolding, this range of activity is necessarily bounded by rules and routines that provide structure for the teacher and the children. Indeed, research has found that teachers who spend time early in the year establishing clear procedures and routines have classrooms in which children become more involved in academic tasks later on.12 Establishing standards with children regarding student safety, classroom order, and decorum is important as long as the rules are few, easy to understand, positively stated, enforceable, and can be generalized across multiple situations and classroom activities. Conclusion The NAEYC Accreditation criteria related to Standard 3 Teaching were designed to reflect developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). Because accreditation is based on demonstrating that the majority of criteria are met, it is not unexpected that as a set, these criteria differentiate programs that are accredited from those that are not. Notably, the criteria include a combination of practices that are necessary to promote safety and classroom See “About the Reliability and Validity Study [ReVal-1]”) 1 See L.E. Berk and A. Winsler, Scaffolding Children’s Learning: Vygotsky and Early Childhood Education (Washington, DC: NAEYC, 1995); E. Bodrova & D.J. Leong. Tools of the Mind: Vygotskian Approach to Early Childhood Education, 2nd ed. (New York: Prentice Hall, 2007). 2 See, for example, S.D. Henderson, J.E. Many, H.P. Wellborn, and J. Ward, “How Scaffolding Nurtures the Development of Young Children’s Literacy Repertoire: Insiders’ and Outsiders’ Collaborative Understandings,” Reading Research and Instruction 41 (Summer 2002): 309–30. 3 See, for example, G.M. Jacobs, “Providing the Scaffold: A Model for Early Childhood/Primary Teacher Preparation,” Early Childhood Education Journal 29, no. 2 (2001): 125–30. 4 Some have called this “classroom engagement.” See N.C. Chien, C. Howes, M. Burchinal, R.C. Pianta, S. Ritchie, D.M. Bryant, R.M. Clifford, D.M. Early, and O.A. Barbarin, “Children’s Classroom Engagement and School Readiness Gains in Prekindergarten,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 81 (September/October 2010): 1534–49. 5 C.M. Connor, F.J. Morrison, and L. Slominski, “Preschool Instruction and Children’s Emergent Literacy Growth,” Journal of Educational Psychology 98 no. 4 (2006): 665–89. 6 4 management (e.g., topics B, C, and D). These aspects of teaching are more likely to be addressed through regulatory requirements and would be reasonably expected in classrooms even without the frame provided by DAP. The topic areas that closely map the construct of scaffolding (topics A, E, F and G) and DAP principles are those that underscore the teacher’s role in supporting children’s learning. Examining the degree to which both topic areas and specific criteria distinguish accredited programs from programs that are not accredited reinforces the centrality of DAP and scaffolding in NAEYC’s standards for instruction. Those criteria were most frequent among the 18 criteria that showed the greatest differences in pass rates between programs. Criteria in topic G (Using Instruction to Deepen Children’s Understanding and Build Their Skills and Knowledge) accounted for 5 of the 18 most discriminating criteria. In topic E (Responding to Children’s Interests and Needs) 6 out of 9 criteria within the topic area were among these 18 with high pass rate differences. The 11 criteria in these 2 topic areas reflect the central ideas in scaffolding. That they are best able to distinguish accredited from not-accredited programs underscores the importance of scaffolding within the NAEYC Accreditation criteria and demonstrates the power of NAEYC Accreditation to distinguish high quality programs that are effectively supporting children’s learning. NAEYC Accreditation is designed to be the mark of quality in early childhood education and this analysis makes evident its ability to set apart high performing programs. G.S. Ashiabi, “Play in the Preschool Classroom: Its Socioemotional Significance and the Teacher’s Role in Play,” Early Childhood Education Journal 35 no. 2 (2007): 199–207. 7 J.F. Christie and B. Enz, “The Effects of Literacy Play Interventions on Preschoolers’ Play Patterns and Literacy Development,” Early Education and Development 3 (July 1992): 205–20. 8 Chien et al. 2010; B. Wasik, “When Fewer Is More: Small Groups in Early Childhood Classrooms,” Early Childhood Education Journal 35 no. 6 (2008): 515–21. 9 L.J. Schweinhart and D.P. Weikart, “Education for Young Children Living in Poverty: Child-initiated Learning or Teacher-directed Instruction?” Elementary School Journal 89 no. 2 (1988): 213–25. 10 See for example B.K. Hamre and R.C. Pianta, “Can Instructional and Emotional Support in the First Grade Classroom Make a Difference for Children at Risk of School Failure?” Child Development 76 (September/ October 2005): 949–76. 11 C.M. Bohn, A.D. Roehrig, and M. Pressley, “The First Days of School in the Classrooms of Two More Effective and Four Less Effective Primary-Grades Teachers,” The Elementary School Journal 104 (March 2004): 269–87. 12