'Tis Enough, 'Twill Serve: Defining Physical Injury Under the Prison

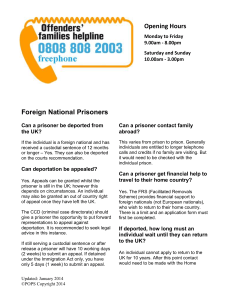

advertisement