ARTICLE

10.1177/1052562903252518

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION:

FOUR APPROACHES TO

MANAGEMENT EDUCATION

Miguel Pina e Cunha

Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal

João Vieira da Cunha

MIT

Carlos Cabral-Cardoso

Universidade do Minho, Portugal

This article argues for the adoption of complicated approaches by management educators. The argument rests on the position that if uncertainty and

ambiguity are inherent to management, particularly in view of the profound

changes that have occurred during recent years in the competitive environments of organizations, there is the need to develop complex managers, that is,

managers more skilled in dealing with uncertainty and ambiguity. Four

approaches (hypertext, dialectics, linkages, and metaphors) are presented to

illustrate complementary ways of operationalizing the logic of complication in

a management education context. These approaches have the potential for

increasing the awareness and alertness of management students to the challenges with which they will probably be confronted in the emerging competitive

landscapes.

Keywords: complication; hypertext; dialectics; linkages; metaphors

Authors’ Note: We gratefully acknowledge the insightful comments from the anonymous

reviewers as well as the suggestions and encouragement from the associate editor, Gordon

Dehler. Address correspondence to Miguel Pina e Cunha, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Rua Marquês de Fronteira, 20, 1099-038 Lisboa, Portugal; e-mail:

mpc@fe.unl.pt.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION, Vol. 28 No. 1, February 2004 88-103

DOI: 10.1177/1052562903252518

© 2004 Organizational Behavior Teaching Society

88

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

89

It is frequently claimed that organizational environments are becoming

more complex and dynamic. To use the words of Bettis and Hitt (1995), new

competitive landscapes are emerging, marked by increasing levels of uncertainty and ambiguity, and leading to what is now known as hypercompetition

(D’Aveni, 1994). Management educators may be interested in accompanying these changes to help managers in shaping organizations in such a way as

to make them willing and able to respond to complex organizational challenges. In brief, it may be advantageous to expose business students and managers to complication.

This article discusses the limits of simplification and how complication

may help to circumvent them. The argument rests on the position that if

uncertainty and ambiguity are inherent to management as a human activity,

they should not be ignored in the context of management education (e.g.,

Gallos, 1997). The gap between the complexity of organizations and the simplicity of educational strategies, however, may be widening because of the

rhetoric of fast action and the diffusion of universal prescriptions (Glynn,

Barr, & Dacin, 2000).

In this article, we discuss some reasons that may lead managers toward a

logic of simplification, the disadvantages of such logic, and how to overcome it. In particular, we discuss why the logic of simplicity may be parsimonious and adequate for ease of comprehension and for purposes of

professional socialization. However, this logic does not elucidate the complicated nature of organizing. The need for complication in management education is therefore advocated. By complication, we refer to the capacity to see

and interpret organizational phenomena from multiple perspectives

(Bartunek, Gordon, & Weathersby, 1983; Dehler, Welsh, & Lewis, 2001;

Weick, 1979).

The article is organized as follows. We start by discussing why current

management theories may be simplistic for interpreting complex environments. We argue that despite criticism, the logic of simplification seems to

prevail, even in the face of contradiction. As a result, the need to develop

complicated understandings through management education is advanced.

We suggest four approaches for complication: hypertext, dialectical thinking, linkages, and metaphors. The article does not address the pedagogy of

complication (for that purpose, see Dehler et al., 2001) but, rather,

approaches to complication, or possible ways of developing complicated

understandings. Before considering the relevance of complication, the logic

of simplification is discussed in the next section.

90

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

The Logic of Simplification

In this section, we aim to answer three questions: (a) What is the logic of

simplification? (b) Why is it so seductive to managers and management educators? and (c) What are its disadvantages? These questions are pertinent in

the sense that organizational behavior depends on interpretations of reality

(e.g., Gherardi, 1998). If people interpret reality as being simple, they will act

accordingly, but an organization (or its environment) does not become simple

because someone perceives it that way. Simplicity, though elegant, is often

untrue (Eisenhardt, 2000).

Nonetheless, simplification thrives in academic models that strive for parsimony and generalizability. Complicated thinking, therefore, is often sacrificed, with organizational researchers and educators acting as homogenizers

of the pluralistic world we live in (Glynn et al., 2000). Many textbooks, for

example, present organizations as relatively simple systems: They do not discuss ambiguity, they ignore the existence of contradictory empirical evidence, they do not discuss ambiguity, and they do not reflect on the frustrations or the areas of ignorance of the research community. To the contrary, as

argued by Fineman and Gabriel (1994), textbook rhetoric is grounded on

solidity and certainty, with many textbooks being described as look-alikes

(Dehler et al., 2001). In these sources, organizations are portrayed as systems

composed of many interrelated parts, which is indeed a measure of complexity, but the rules for organizing these parts are laid out as if grounded on solid

evidence. Such rules can be accessed through a Newtonian mind-set that

management has appropriated and improved upon since the inception of the

discipline. It is based on a simplification- and segmentation-based approach

that seems to resist the challenges of post-Newtonian science. More than

textbook rhetoric, however, simplicity may be an ingrained characteristic of

organization theory. As discussed by Boulding (1956) in his classification of

systems complexity, there is a discrepancy between the degree of organizational systems complexity and the complexity of the models developed in the

social sciences to study such systems. As noted by the author, organizations

are often analyzed on the basis of “overly simple mechanical models,”

whereas organizational systems are “far beyond our ability to formulate”

(p. 207).

Simplified representations of organizations may be misleading because

they distract us from the essential: how to prepare people for the essence of

organizing, that is, ambiguity and interpretation (Daft & Weick, 1984). If

managers seem to be selective and consistent in their interpretations, the reinforcement of such a tendency through management education will not only

legitimize but also bolster the tendency toward simplification (e.g., Starbuck

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

91

& Milliken, 1988). Simplicity or “the narrowing, increasingly homogeneous

managerial ‘lenses’ or world views” (Miller, 1993, p. 117) may be developed

by managers as a result of education and experience, spearheading a growing

desire for further simplification. In fact, confidence in past accomplishments

may lead to a decrease in the motivation to seek information (Ashford &

Cummings, 1983). This, in turn, may result in a reduced sensitivity to environmental change, as this sensitivity depends on the amount of information

sought (Daft & Weick, 1984). Additionally, managers seem to prefer information that is congruent rather than incongruent with their own perspective

(Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984). All of the above suggests that simplification

may be a management tendency and that people often overvalue a particular

perspective, precluding competing views or undervaluing their relevance.

Miller and Chen’s (1994, 1996) empirical research confirmed the perils of

simplification by showing that oversimplification may be harmful for organizational practice. As such, it may be wrong to reinforce the simplification

agenda in educational settings instead of exposing students/managers to the

risks it may involve.

Furthermore, when more and diverse descriptions of a system are offered,

the perception ensues that it is complex, with subsequent managerial action

potentially reflecting such elaboration (Tsoukas & Hatch, 2001). Under contrasting views, managing no longer means learning to better use the very

same set of rules but instead learning the system from a different set of

rules—a distinction that echoes the discussion on single- and double-loop

learning (Argyris & Schön, 1978).

Multiple understandings (e.g., theoretical diversity, alternative frameworks) may constitute a good way for improving management learning and

performance, as empirically demonstrated by Kilduff, Angelmar, and Mehra

(2000). A look at management education, however, shows that discourse and

prescription are often engaged in the pursuit of simplicity. Why, for example,

do management textbooks and managerially orientated prescriptions insist

on the presentation of relatively simple theories of organization? Why do

some managerial techniques of dubious value achieve enormous popularity?

A possible answer is that simple theories have the appeal of elegance and universality. Simple heuristics may not reflect the functioning of organizations

but does provide a perception of control that may be a valuable psychological

resource for people trying to make sense of and act upon complex

organizations.

In the next section, we discuss four possibilities for avoiding the limitations of simplification: hypertext, dialectical thinking, linkages, and

metaphors.

92

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

Escaping From Simplicity

Having discussed the logic of simplification and its limitations, we now

examine some means for overcoming it. A critical moment in the simplicity/

complication debate was Weick’s (1979) defense of the need to raise complicated understandings: “complicate yourself” (p. 261). This argument may be

best understood through reference to the law of requisite variety, which for

our purposes can be described as arguing that it takes a complex theory to understand a complex organization. Considering that to deal with variety one

needs variety, if the environment is full of variety, organizations in such an

environment must be similarly varied. Returning to Weick,

If a simple process is applied to complicated data, then only a small portion of

that data will be registered, attended to, and made unequivocal. Most of the

input will remain untouched and will remain a puzzle to people concerning

what is up and why they are unable to manage it. (p. 189)

The defense of complicated understandings of organizations has deep

roots in the social sciences (see Bartunek et al., 1983). Because organizations

and environments are complex, they cannot be captured with “simple

mechanical models” (Boulding, 1956, p. 207). Therefore, an important role

for management educators is to help students achieve complicated

understandings.

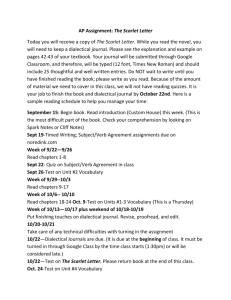

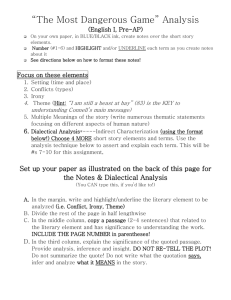

In this section, we introduce our typology of approaches to complication,

which is depicted in Figure 1. The typology revolves around two dimensions:

the first refers to ontology and the second to epistemology.

The first dimension, then, refers to the ontological assumptions about the

nature of management and organizations. Two possibilities are explored: independence and interdependence. The independence perspective is based on

the premise that different units of meaning coexist within what is conventionally called an organization and that a given unit has a reality of its own. For

example, organizational-, group-, and individual-level dynamics have idiosyncratic features that can be analyzed independently. These levels, of

course, can be linked, but they can also be considered to be sufficiently independent to be studied by different scientific communities. Each community

should therefore explore a given feature of the organizational reality, with the

cumulative efforts of the research community as a whole putting together the

pieces of knowledge created independently. In the same sense, independent

metaphorical views can be developed, which provide different images of

organization. Each metaphor develops a unique understanding of the organization, which needs to be challenged by competing metaphors. The power of

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

93

epistemology

Integration

Hypertext

Linkages

ontology

Interdependence

Dialectics

Independence

Metaphors

Differentiation

Figure 1:

A Typology of Complication Approaches

metaphor resides in its capacity to provide independent representations of

reality. Under a perspective of interdependence, in turn, knowledge is created

through the simultaneous focus on multiple units of meaning. In this case, the

focus is on the inner complexities of organizing. Cross-level impacts and

management paradoxes illustrate the interdependence perspective, which

highlights the tensions and ambiguities of organizational life. Several arguments provide evidence favorable to the interdependence perspective. For

example, the transition from one level to the next is not linear. In the same

sense, organizations seem to be pervaded by paradox and contradiction.

The second dimension refers to epistemological issues. Two major

approaches are considered: differentiation, which considers that a given

topic may be better understood by decomposing it into its constituent parts

(or representations or tensions); and integration, which focuses on the aggregate properties of a system instead of on its microcomponents (organizational dynamics are the emergent results of the interactions taking place at

lower levels of analysis). Each of these approaches has a long history in man-

94

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

agement as well as in other research fields. Traditional approaches to management were based on the logic of differentiation. We can consider, for

example, the cases of scientific management, bureaucratic theory, strategic

planning, and management by objectives: They all approach organizations

on the basis of differentiation and accept that the world should be approached

through analysis. The logic of integration, in turn, is the essence of systems

thinking, from Von Bertalanffy (1956) to Katz and Kahn (1978). It is also

present, for example, in the gestalt psychology school. According to this perspective, the whole is more than the sum of its parts, and understanding those

parts may not lead to knowing the whole. Integration may also be considered

the hallmark of the complexity approach to management, which focuses on

the emergent properties of organizations (e.g., Eisenhardt & Bhatia, 2002),

meaning that one should pay less attention to reified things and more to ongoing processes. Through integration, one aims to acquire knowledge by combining different elements. Integration highlights the recursive nature of organizing, whereas differentiation delves into multiplicity by challenging one

representation with another.

The combination of these dimensions results in four different approaches:

hypertext (integration/interdependence), dialectical thinking (differentiation/interdependence), linkages (integration/independence), and metaphors

(differentiation/independence). These approaches are described below.

HYPERTEXT

The hypertextual approach pursues complication through integration and

interdependence: students are invited to explore the tight connections between closely related phenomena. In a hypertextual logic, organizational

phenomena should be studied according to a major perspective (e.g., the

rational perspective), without excluding other perspectives from the analysis

(e.g., the emotional perspective). The different perspectives are approached

as interdependent processes in the sense that what matters is to approach phenomena from one perspective while keeping another active. The way phenomena are intertwined thus constitutes a major challenge for this approach.

To explore this approach, we find the work of Jerome Bruner (1986) particularly relevant. Bruner argued that there are two modes of cognitive functioning: a logic-scientific mode and a narrative mode. The first mode pursues

general laws or rules that may help discover a scientific truth. The second is

focused on the specificities of human experience, being context dependent,

historically situated, and based on personal experience. Tsoukas and Hatch

(2001) transferred this model to the field of organization studies, showing

that both modes have been used by organizational scholars.

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

95

The contrast between the logic-scientific and narrative modes of thought

echoes the art versus science debate. Guillén’s (1997) analysis of the aesthetics of Taylorism provides an illustration of these complementarities, showing

that beneath the scientific approach there is an aesthetic possibility waiting to

be uncovered. The organization can thus be read not as palimpsest but as

hypertext (Nonaka & Ichijo, 1997). Taking organizations as palimpsests

means that one views them as manuscripts from which the original writing

must be erased before rewriting its surface. In the case of the hypertextual

view, different layers coexist and can be accessed and recombined in several

ways.

As an example, consider how valuable the complementary use of outside

(rational, objective, distanced) and inside (personal, subjective) perspectives

may be in instructional contexts. The two versions of Pascale and

Christiansen’s (1983a, 1983b) analysis of Honda’s entry in the American

market illustrate hypertextuality in the context of management education.

Case discussions can switch from one version to the other in search of multiple truths. Alternatively, the truths may be combined with one another and

with real-life stories to stretch theories, exposing both their usefulness and

limitations. The gap between organization science and organization reality

(Frost, Mitchell, & Nord, 1992) may thus be bridged through hypertextuality,

or the practice of integrating interdependent perspectives.

DIALECTICAL THINKING

The dialectical approach operates through differentiation and interdependence. In a dialectical relationship, a thesis is at the origin of its antithesis and

both are used to reach a synthesis. Students can be asked to differentiate thesis and antithesis, exposing the paradoxical nature of organizational phenomena. Considering the complicated interplay of opposites, students may then

be guided through an exploration of paradox and stimulated to discover possible syntheses. Syntheses should not be understood as means for solving

paradoxes, in the sense of removing an essential feature of contradiction, but

as vehicles for infusing management knowledge with the idea of “permanent

paradoxes” (Clegg, Cunha, & Cunha, 2002). By permanent paradoxes, we

refer to the recognition that by exposing tension while retaining contradiction and assuming the permanence of paradox, scholars stimulate the search

for complicated understandings of organizations.

The dialectical view takes organizational topics as phenomena where two

opposing entities engage each other in conflict, generating a synthesis that

incorporates and differs from both of them while retaining an inner paradoxical nature. This approach thus involves two contradictory entities: the

96

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

engagement of these entities in a conflict and the emergence of a different

entity as a product of that conflict. According to Webster and Starbuck

(1988), leadership theories afford an example of synthesis between a traditional model, based on the superiority of matching firm superiors/obedient

subordinates, and the opposing views from Chester Barnard and the Hawthorne studies that assert the advantage of friendlier supervisors and more

participative subordinates. The Ohio leadership studies (e.g., Fleishman &

Harris, 1962) synthesized these antithetical views by pulling together different dimensions of the same concept.

Organizational dialectics refers not only to recombining knowledge but

also to generating new knowledge on the basis of exploring the available

knowledge from different perspectives. Diverse pedagogical approaches

have been proposed for increasing complex-thinking skills on the basis of

dialectics, including the use of conceptual polarities, personal contradictions, and paradoxical predicaments (Lewis & Dehler, 2000). The dialectical

approach represents a provocative mode of knowledge generation in the

sense that it goes beyond acknowledging the existence of opposites. For

example, if there are two competing views on a certain phenomenon A (+A

and –A), a dialectical approach will go one step further than, say, metaphorical thinking. It will not simply accept diversity as a given from which one

should pick the best framework for interpretation, nor will it force the choice

of a spot somewhere on the –A to +A continuum. It will lead, instead, to the

creation of a new theoretical entity, combining knowledge from the two previous instances (±A).

The potential of dialectical thinking to organizational analysis and management learning has received growing interest in recent years. Evidence

on its usefulness arrived from such diverse topical areas as organizational

change (Van de Ven & Poole, 1995), strategic management (Schweiger,

Sandberg, & Ragan, 1986), and theory building (Lewis, 2000; Lewis &

Grimes, 2000). Other sources that can be used to guide students through the

dialectical route to complication include those indicated below. Kamoche

and Cunha (2001) discussed how freedom and control can be synthesized in

minimal structures. Edelman and Benning (1999) pointed out the possibility

of incremental-punctuated organizational change. Yates and Orlikowski

(1999) illustrated how organizational communication can be at once formal

and informal. Brews and Hunt (1999) contended that strategy can be simultaneously emergent and deliberate. Eisenhardt and Sull (2001) discussed how

simple rules may be adequate for complex environments. These authors

strived, implicitly or explicitly, to demonstrate the pervasiveness of paradox

in organizational life and the potential of dialectics to provide insights for

tackling paradoxes.

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

97

In the educational context, dialectical thinking may be useful in helping

students break the dichotomous either/or view of organizations. By inviting

the search for synthetic views, the dialectical perspective stimulates “out of

the box” thinking and provides a path for revealing organizational tensions

and dilemmas.

LINKAGES

In the linkages approach, subjects are asked to integrate objects that are

often taken as independent. Linkages refer to the connections between activities and outcomes across units and/or levels (Goodman, 2000). We all know,

of course, that levels are related. But because of analytical clarity and disciplinary boundaries, most researchers actually treat them as independent. As a

result, some authors called for the need to develop meso-level theories

(House, Rousseau, & Thomas, 1995), whereas others noted the schizophrenic nature of organization studies (O’Reilly, 1991) because of the great

(macro-micro) divide. Each level can be analyzed without reference to other

levels, meaning that they can be conceptually separated. This separation does

not, however, eliminate the multiple influences between levels. For example,

job satisfaction tends to be studied as an individual-level variable. Nonetheless, there is a potential cross-level continuity. At the aggregate level, job

satisfaction will influence organizational climate. As such, levels can be separated for analytical purposes, but they influence each other on an ongoing

basis.

The study of organizational linkages is relevant for understanding the

complexity of organizations. It rests on the level of analysis perspective that

is recurrent in organization studies. However, it goes one step further: Here,

the complex web of cross-level relationships is not left unquestioned, as it

frequently is in the level of analysis perspective.

In fact, despite the common use of levels of analysis as conceptual frameworks, interactions between levels have been left relatively unexplored.

Despite the efforts of authors such as Rousseau (1985) and Roberts, Hulin,

and Rousseau (1978), the implicit assumption of most research is that there is

cross-level continuity. As such, improvements at one level will lead to

improvements at the other levels. Many examples show that this is not necessarily the case. Evidence from the so-called productivity paradox shows that

changes at one level may not be easily transferred to other levels, exposing

the dangers of the continuity assumption. The productivity paradox basically

argues that large investments in information technology may not result in significant productivity improvements at the organizational or industry level

(Attewell, 1994). Methodologically, Chan (1998) discussed how the specifi-

98

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

cation of constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis

guides the way phenomena are perceived. His illustration of composition

models with the concept of organizational climate shows a shifting concept,

the contours of which depend on how the cross-level analysis of climate is

defined and conducted.

The linkages perspective may be valuable for instructional purposes

because it provides evidence that concepts do not just become bigger when a

macro view is adopted. Rather, they change qualitatively and their effects

may be metamorphosed, neutralized, or amplified. As such, the focus on

linkages may challenge the “peaceful” micro-macro journey so often portrayed in the literature.

METAPHORS

Metaphors complicate organizational thought through polarization. Independent objects are differentiated by subjects. While creating one particular

truth, each metaphor excludes other truths (Morgan, 1997). It therefore introduces an element of discontinuity between truths, making them conceptually

separated. Metaphors tend to be used in sequence, with one metaphor dominating at a certain moment. This is particularly evident in the case of emerging research topics. Organizational improvisation research, for example, is

dominated by the jazz metaphor (Kamoche, Cunha, & Cunha, 2002). Probably, more research will bring metaphorical diversity.

Complication through metaphor assumes that it is insufficient to regard

organizations as phenomena reducible to a single view. On the contrary,

organizations must be taken as complex realities that are better seen through

multiple lenses. The metaphorical approach to complication consists of adding different views to the analysis.

Metaphor may be described as “a way of thinking and a way of seeing that

pervade how we understand our world generally” (Morgan, 1997, p. 4). This

“way of seeing/thinking” allows for the drafting of the characteristics of a

particular phenomenon by means of another phenomenon. To explore the

potential of a metaphor, the metaphorical object must be perceived as similar

to the original object of study. Second, it must be a topic with which we are

more knowledgeable than the original. Weick (1999) emphasized this point

while asserting “If you want to study organizations, study something else”

(p. 541). Thus, a metaphor is useful because it allows the study of a phenomenon that is understood by means of another, for which a deeper knowledge

exists.

When we realize that organizations can only be grasped by recognizing

their multifaceted nature, we become aware of the limitations of using a sin-

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

99

gle metaphor to develop organizational interpretations. The metaphorical

approach is relevant because—acknowledging that every metaphor distorts

the object under investigation—it invites students to approach the object

from multiple angles. Each metaphor exposes the advantages and limitations

of competing metaphors, signaling the risks of simplified representations of

organizations.

Moving from one metaphor to another requires a new set of assumptions

independent from one another. This may be stimulating in the educational

context, as it invites students to engage in a personal exploration of the different faces of organizations. “Diversity games” (e.g., Beazley & Lobuts, 1998)

provide an example of how to put the metaphorical approach into practice,

leading students in their explorations of the multiple images of organization.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, we have proposed four ways to develop complicated understandings in management education. The argument is not original. It integrates the previous research conducted by scholars such as Weick (1979),

Bartunek et al. (1983), Lewis and Dehler (2000), and Dennehy, Sims, and

Collins (1998), among others. We believe our article makes a contribution to

the management literature by contrasting possible routes to complication.

With this article, we aim to help make complication less exceptional in the

context of management education (Lewis & Dehler, 2000). Thus far, the

exceptional character of complicated approaches may be a consequence of

myriad causes ranging from culture to educational practice. Culturally, the

mind-sets of Westerners seem to be structured in terms of oppositions, which

makes it difficult, for example, to engage them in dialectical synthesis (Peng

& Nisbett, 1999). Regarding educational practice, the increasing mechanization of the teaching process should be considered as a possible cause of standardized educational contents (Lundberg, 1994).

We discussed four approaches as possibilities for helping managers and

management students to raise complicated understandings: hypertext, dialectical thinking, linkages, and metaphors. These approaches correspond to

analytical categories that can be put into operation through the use of colliding case studies (Pascale & Christiansen, 1983a, 1983b), contrasting frameworks for analyzing the same case (Mair, 1999), multiple teaching

approaches (Bartunek et al., 1983), diverse teaching materials such as novels

and films (Champoux, 1999; Czarniawska-Joerges & Monthoux, 1994),

devil’s advocacy (Cosier & Aplin, 1980), and dialectical inquiry (Mitroff &

Mason, 1981). The pervasiveness of simplification-driven cognitive pro-

100

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

cesses, such as stereotyping and categorization (e.g., undervaluing situational variables, attributing poor performance to dispositional characteristics, and so forth; Mitchell & Wood, 1980; Ross, 1977), makes the claim for

complication more pertinent in a time of great environmental change. The

approaches outlined here should not be viewed as mutually exclusive. For

example, contrasting a case on the basis of objective/subjective views is characterized as a hypertextual approach. However, such an approach may also

be used to elicit paradox and contradiction (Dehler & Welsh, 1993), which

would make it closer to the quadrant of dialectical thinking. Combinations

may thus be explored.

In this discussion, we started from the assumption that there is a gap between practical activity and management learning. Practical activity is understood by different people in different ways and is not available as an objective

given (Boje, 1995; Packer, 1985). The gap resides in the observation that

diversity should be as normal in management education as it is in the real

world. We believe it is not. Our position, thus, is that instead of simple and

easy-to-use truths, different and sometimes divergent interpretations could

be offered. These could constitute a means for developing more complex

people to match simpler structures. This would reverse the functionalistbureaucratic logic, where simple people are prepared to work within the context of complex structures. This shift, we believe, may be one of the major

challenges for management educators in the years ahead.

References

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ashford, S. J., & Cummings, L. L. (1983). Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32, 370398.

Attewell, P. A. (1994). Information technology and the productivity paradox. In D. H. Harris

(Ed.), Organizational linkages: Understanding the productivity paradox (pp. 13-53). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Bartunek, J. M., Gordon, J. R., & Weathersby, R. P. (1983). Developing “complicated” understanding in administrators. Academy of Management Review, 8, 273-284.

Beazley, H., & Lobuts, J. (1998). Systems and synergy: Decision making in the thirdmillennium. Simulation & Gaming, 29, 441-449.

Bettis, R. A., & Hitt, M. A. (1995). The new competitive landscape. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 7-19.

Boje, D. M. (1995). Stories of the storytelling organization: A postmodern analysis of Disney as

Tamara-Land. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 997-1035.

Boulding, K. E. (1956). General systems theory: The skeleton of science. Management Science,

2, 197-208.

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

101

Brews, P. J., & Hunt, M. R. (1999). Learning to plan and planning to learn: Resolving the planning school/learning school debate. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 889-913.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Champoux, J. E. (1999). Film as a teaching resource. Journal of Management Inquiry, 8, 206217.

Chan, D. (1998). Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different

levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83,

234-246.

Clegg, S. R., Cunha, J. V., & Cunha, M. P. (2002). Management paradoxes: A relational view.

Human Relations, 55(5), 483-503.

Cosier, A., & Aplin, J. C. (1980). A critical view of dialectical inquiry as a tool in strategic planning. Strategic Management Journal, 1, 343-356.

Czarniawska-Joerges, B., & de Monthoux, P. G. (Eds.). (1994). Good novels, better management. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood.

Daft, R. L., & Weick, K. E. (1984). Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems.

Academy of Management Review, 9, 284-295.

D’Aveni, R. (1994). Hypercompetition. Managing the dynamics of strategic maneuvering. New

York: Free Press.

Dehler, G., & Welsh, M. (1993). Dialectical inquiry as an instructional heuristic in organization

theory and design. Journal of Management Education, 17, 79-89.

Dehler, G., Welsh, M., & Lewis, M. W. (2001). Critical pedagogy in the “new paradigm”:

Raising complicated understanding in management education. Management Learning, 32,

493-511.

Dennehy, R. F., Sims, R. R., & Collins, H. (1998). Debriefing experiential learning exercises: A

theoretical and practical guide. Journal of Management Education, 22, 9-25.

Edelman, L. F., & Benning, A. L. (1999). Incremental revolution: Organizational change in

highly turbulent environments. Organization Development Journal, 17, 79-93.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (2000). Paradox, spirals, ambivalence: The new language of change and pluralism. Academy of Management Review, 25, 703-705.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bhatia, M. M. (2002). Organizational complexity and computation. In

J. A. C. Baum (Ed.), Companion to organizations (pp. 442-466). Oxford: Blackwell.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Sull, D. N. (2001). Strategy as simple rules. Harvard Business Review,

79(1), 107-116.

Fineman, S., & Gabriel, Y. (1994). Paradigms of organizations: Exploration in textbook

rhetorics. Organization, 1, 375-399.

Fleishman, E. A., & Harris, E. F. (1962). Patterns of leadership behavior related to employee

grievances and turnover. Personnel Psychology, 15, 43-56.

Frost, P. J., Mitchell, V. F., & Nord, W. R. (1992). Organizational reality: Reports from the firing

line (4th ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

Gallos, J. V. (1997). On learning about diversity: A pedagogy of paradox [Editor’s corner]. Journal of Management Education, 21, 152-154.

Gherardi, S. (1998). Competence—The symbolic passe-partout to change in a learning organization. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 14, 373-393.

Glynn, M. A., Barr, P. S., & Dacin, M. T. (2000). Pluralism and the problem of variety. Academy

of Management Review, 25, 726-734.

Goodman, P. S. (2000). Missing organizational linkages. Tools for cross-level research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guillén, M. (1997). Scientific management’s lost aesthetic: Architecture, organization, and the

Taylorized beauty of the mechanical. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 682-715.

102

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION / February 2004

House, R. J., Rousseau, D. M., & Thomas, M. (1995). The meso paradigm: A framework for the

integration of macro and micro organizational behavior. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw

(Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 15). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Kamoche, K., & Cunha, M. P. (2001). Minimal structures: From jazz improvisation to product

innovation. Organization Studies, 22, 733-764.

Kamoche, K. N., Cunha, M. P., & Cunha, J. V. (Eds.). (2002). Organizational improvisation.

London: Routledge.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). New York:

John Wiley.

Kilduff, M., Angelmar, R., & Mehra, A. (2000). Top management-team diversity and firm performance: Examining the role of cognitions. Organization Science, 11, 21-34.

Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of

Management Review, 25, 760-776.

Lewis, M. W., & Dehler, G. E. (2000). Learning through paradox: A pedagogical strategy for

exploring contradictions and complexity. Journal of Management Education, 24, 708-725.

Lewis, M. W., & Grimes, A. J. (2000). Metatriangulation: Building theory from multiple paradigms. Academy of Management Review, 24, 672-690.

Lundberg, C. (1994). Techniques for teaching OB in the college classroom. In J. Greenberg

(Ed.), Organizational behavior.: The state of the science (pp. 221-244). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mair, A. (1999). Learning from Honda. Journal of Management Studies, 36, 25-44.

Miller, D. (1993). The architecture of simplicity. Academy of Management Review, 18, 116-138.

Miller, D., & Chen, M. J. (1994). Sources and consequences of competitive inertia: A study in the

U.S. airline industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 1-23.

Miller, D., & Chen, M. J. (1996). The simplicity of corporate repertoires: An empirical analysis.

Strategic Management Journal, 17, 419-439.

Mitchell, T. R., & Wood, R. E. (1980). Supervisors’ responses to subordinate poor performance:

A test of an attributional model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,

25, 123-128.

Mitroff, I. I., & Mason, R. O. (1981). The metaphysics of policy and planning: A reply to Cosier.

Academy of Management Review, 6, 649-652.

Morgan, G. (1997). Images of organization (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nonaka, I., & Ichijo, K. (1997). Creating knowledge in the process organization: A comment on

Denison’s chapter. In P. Shrivastava, A. S. Huff, & J. E. Dutton (Eds.), Advances in strategic

management (Vol. 14, pp. 45-52). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Nystrom, P. C., & Starbuck, W. H. (1984). To avoid organizational crises, unlearn. Organizational Dynamics, 12(4), 53-65.

O’Reilly, C. A. (1991). Organizational behavior: Where we’ve been, where we’re going. Annual

Review of Psychology, 42, 427-458.

Packer, M. J. (1985). Hermeneutic inquiry in the study of human conduct. American Psychologist, 40, 1081-1093.

Pascale, R. T., & Christiansen, E. T. (1983a). Honda (A). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Pascale, R. T., & Christiansen, E. T. (1983b). Honda (B). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (1999). Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. American Psychologist, 54, 741-754.

Roberts, K. H., Hulin, C. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1978). Developing an interdisciplinary science

of organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cunha et al. / LOOKING FOR COMPLICATION

103

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attributional process. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10,

pp. 173-220). New York: Academic Press.

Rousseau, D. M. (1985). Issues of level in organizational research: Multi-level and cross-level

perspectives. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior

(Vol. 7, pp. 1-37). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Schweiger, D. M., Sandberg, W. R., & Ragan, J. W. (1986). Group approaches for improving

strategic decision making: A comparative analysis of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy,

and consensus. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 51-71.

Starbuck, W. H., & Milliken, F. (1988). Challenger: Fine-tuning the odds until something breaks.

Journal of Management Studies, 25, 319-340.

Tsoukas, H., & Hatch, M. J. (2001). Complex thinking, complex practice: The case for a narrative approach to organizational complexity. Human Relations, 54, 979-1013.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining development and change in organizations.

Academy of Management Review, 20, 510-540.

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1956). General systems theory. General Systems: Yearbook of the Society

for General Systems Theory, 1, 1-10.

Webster, J., & Starbuck, W. H. (1988). Theory building in industrial and organizational psychology. In C. L. Cooper & I. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 93-138). London: Wiley.

Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: AddisonWesley.

Weick, K. E. (1999). The aesthetic of imperfection in orchestras and organizations. In M. P.

Cunha & C. A. Marques (Eds.), Readings in organization science (pp. 541-563). Lisbon:

ISPA.

Yates, J., & Orlikowski, W. J. (1999). Knee-jerk anti-LOOPism and other e-mail phenomena:

Oral, written, and electronic patterns in computer-mediated communication (Tech. Rep. No.

150). Cambridge, MA: Center for Coordination Science.

Request Permission or Order Reprints Instantly

Interested in copying, sharing, or the repurposing of this article? U.S. copyright law, in

most cases, directs you to first get permission from the article’s rightsholder before using

their content.

To lawfully obtain permission to reuse, or to order reprints of this article quickly and

efficiently, click on the “Request Permission/ Order Reprints” link below and follow the

instructions. For information on Fair Use limitations of U.S. copyright law, please visit

Stamford University Libraries, or for guidelines on Fair Use in the Classroom, please

refer to The Association of American Publishers’ (AAP).

All information and materials related to SAGE Publications are protected by the

copyright laws of the United States and other countries. SAGE Publications and the

SAGE logo are registered trademarks of SAGE Publications. Copyright © 2003, Sage

Publications, all rights reserved. Mention of other publishers, titles or services may be

registered trademarks of their respective companies. Please refer to our user help pages

for more details: http://www.sagepub.com/cc/faq/SageFAQ.htm

Request Permissions / Order Reprints